|

LITR 5439 Literary & Historical Utopias |

|

Marisela N. Caylor

July 2, 2013

Oryx and Crake:

My Gateway to the World of Speculative Fiction

What had been altered was nothing less than the ancient primate brain. Gone were

its destructive features, the features responsible for the world’s current

illnesses. For instance, racism—or, as they referred to it in Paradice,

pseudospeciation—had been eliminated in the model group, merely by switching the

bonding mechanism: the Paradice people simply did not register skin color.

Hierarchy could not exist among them, because they lacked the neural complexes

that would have created it. Since they were neither hunters nor agriculturalists

hungry for land, there was no territoriality: the king-of-the-castle hard-wiring

that had plagued humanity had, in them, been unwired. They ate nothing but

leaves and grass and roots and a berry or two; thus their foods were plentiful

and always available. Their sexuality was not a constant torment to them, not a

cloud of turbulent hormones; they came into heat at regular-intervals, as did

most mammals other than man.

--Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood’s 2003 novel, Oryx

and Crake is one of the most complex, entertaining, and fantastic books I

have ever read. When reading this novel, there were times when I would think to

myself “how real” this world actually seems.

Oryx and Crake was my “gateway” book

into the world of Speculative Fiction, which I had never heard of before taking

this course. Speculative fiction is a broad genre and covers so much territory

and provides a unique blend of entertainment and information. It serves to

entertain and educate its readers while maintaining certain conventions that may

or may not adhere to one type of genre. The beauty of speculative fiction is it

is a hybrid of so many other genres, can appeal to many types of readers, and

can be taught within a wide range of disciplines while still maintaining its

own identity. The purpose of this essay is to expose

Oryx and Crake as the gateway to

different ways of exploring Utopian Literature, to compare/contrast Atwood’s

novels with other Utopian novels, and explore the strengths and opportunities of

blending genres within Speculative Fiction.

In my opinion, Oryx and Crake

is a perfect hybrid of all the Utopian novels that we read throughout the

semester and worthy of closer examination. The novel proves that speculative

fiction draws inspirations and conventions from other genres like science

fiction, fantasy, and adventure/travel narratives but does so in a way that does

not alienate specific readers of each genre. Margaret Atwood states the

lineage of Speculative Fiction “traces back to Jules Verne, who wrote about

things that he could see coming to pass that were possible on the Earth—this

wasn’t about outer space or space invasions—but things that we could actually

do” (Rothschild 3). Atwood’s

explanation allows her audience to look past the “genre” or “label” and think in

terms of a broader genre, something that does not fit into a neat little

category. Speculative Fiction allows its authors to take from and “bend” these

conventions to what they see fit within their work (Obj. 1b.). In “The Road to

Ustopia,” Margaret Atwood describes “bendiness of terminology, literary

gene-swapping, and inter-gene visiting has been going on in the SF world-loosely

defined—for some time” (3). This “bendiness” allows Atwood’s novel to explore

different worlds without adhering to one type of genre which at times, can

alienate readers of a specific genre or pave the way for new readers.

Speculative Fiction possesses conventions that are similar to other

genres including Utopian Literature, Science Fiction, and conventional novels.

In Oryx and Crake, we see more

dystopia rather than utopia, millennial events, journey through time as Snowman

narrates his story, a love interest in Oryx, and Socratic dialogue with Crake.

Margaret Atwood calls this novel “ustopia—a world made up by combining utopia

and dystopia—the imagined perfect society and its opposite—because, in my view,

each contains a latent version of the other” (4).

In the novel it would be safe to say, the dystopia is the world Snowman

was left with and utopia would be the world Crake thought he was to create with

the Crakers. I chose the epigraph for this paper to demonstrate Atwood’s

description of the Crakers as a utopian principle. The entire passage sounds

like utopia, except in the novel, I feel utopia is created through people not a

place. Eventually, if things would have

worked in Crake’s favor, the Crakers would create a utopian world, but he built

his utopia by creating an ideal species that would then create the perfect

paradise (Obj. 3a.). This ideal is tested where our goal is “to review

historical, nonfiction attempts by “communes,” intentional communities, nations,

or cults to institutionalize or practice utopian ideals” (White 2).

In Oryx and Crake, this objective is challenged in how ideal inhabitants of utopia are created first rather than the other way around (Obj. 3c.). Objective 3c. asks the question: “How may utopian studies shift the usual American arguments over race, sex, faith and gender to cultural socio-economic class?” Atwood has addresses this question in Oryx and Crake by the creation of the Crakers. Through the Crakers, all of humans’ ills were expunged by Crake and only the good things about humans and animals were combined to make an ideal hybrid of human/animal species. However, the Crakers live in a world not free of humans, so we are under the impression that some of their behavior will appeal to the Crakers and run the risk of “infecting” Crake’s perfect species. The human nuances and negatives like racism, greediness, ambition, and gender inequality is absent in the Crakers. I feel Crake’s utopia would have been ideally successful, but I still have reservations of ever finding an absolutely perfect utopia in reality or in Literature. Atwood’s novel serves the “Literature of Ideas” perspective by offering its readers “texts that goes beyond literary style or literary history” (White 3). Atwood weaves several genres into one great novel and offers the audience a taste of what can actually happen on Earth if we become too greedy and irresponsible.

The

conventions that Oryx and Crake demonstrates are typical in Utopian Literature

but Atwood adds her own take on how these conventions play into her work.

The novel Oryx and Crake includes: a

“hero” in Snowman/Jimmy, a love interest in Oryx, and a “guide” figure through

Crake. These three conventions prove to be the most important taken from Utopian

Literature to move the plot further and allow the audience to find out why

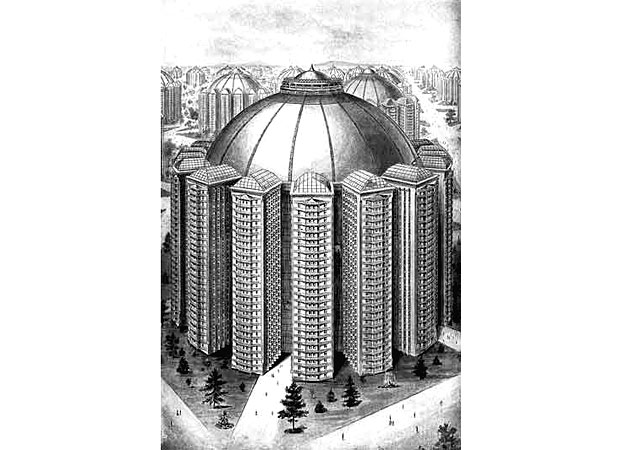

Snowman is living in ruins with these strange people. Crake functions as a guide

through a “hypothetical” utopia when Jimmy visits him at Watson-Crick and later,

at the Paradice dome where Crake is creating the Crakers. Oryx is a guide/love

interest for Snowman as well but she is there to make sure that Jimmy takes care

of the Crakers, that is why she is present to ensure their survival. Through

Oryx, Crake ensures his legacy will live on by manipulating Jimmy into thinking

she loves him when all she is trying to do is save Crake’s vision of utopia.

These three conventions of Utopian Literature are equally important in our other

novels and seem to be the formula that makes these novels entertaining and

informative.

As we studied Atwood’s novel in our course, it was relevant in many ways to help

students understand how utopian literature branches out into other genres.

Oryx and Crake is the perfect

combination of all the novels we read in the class and still maintains its place

in Utopian Literature because of its “bendiness” of the genre. One of those

genres that Utopian Literature branches out from is Science Fiction. In “Science

Fiction: The Literature Ideas,” authors Gilks, Fleming, and Allen described

science fiction as a genre as not “just concerned with science, but with its

consequences. It asked “what if?” What if a world existed in which this or that

were true?” (2). Based on this definition, Atwood does an amazing job at

integrating utopian conventions, dystopian elements, science fiction, romance,

and millennial events while keeping the genre snobs at bay. Her work is

remarkable and no matter what “genre” this novel ends up in at the bookstore or

on Amazon.com, her prose, plot, and psychology of characters is what sets her

work apart from other Utopian Literature. In

Oryx and Crake, there is no physical

journey anywhere until the end of the novel; the journey exists through

revisiting Snowman’s past memories as he is thinking about them. This device

does not become stagnant and wordy like in More’s

Utopia; the readers actually feel

movement through Jimmy’s vivid memories of recalling the past that led to the

“waterless flood.” Another useful way to examine

Oryx and Crake would be to compare it

to some other Utopian texts we read in our seminar and determine how each one

defines the genre of Utopian Literature.

Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s

Herland (1915) and Ernest Callenbach’s

Ecotopia (1975)

are definitive Utopian novels. What I mean by definitive is these novels

contain many of the conventions of Utopian Literature. These novels provide

numerous examples of talkiness and long-winded nature of utopia, but they are

still great novels to read. However, when the men visiting Herland were sitting

through rigorous history lessons about the country, learning about the meaning

of motherhood, and the importance or the children, the prose becomes too talky

and long-winded. The text began to become more tract than novel. In

Ecotopia, Weston is treated to long Socratic dialogues while visiting the

factories about the origin of Ecotopia much like the men visiting Herland. This

is one of the consequences of Utopian Literature. They are fun to talk about and

learn about but when discovering the answers behind the origin of the

civilization, the reader feels more educated than entertained. However in

Oryx and Crake, Atwood invents a land

where an "ustopia exists" and we learn about this disaster through one man’s

perspective, like in Ecotopia.

Through a series of memories, the reader examines along with Snowman how he

participated and possibly, ignored an impending Apocalypse that his best friend,

Crake was planning all along. This realization comes with a price and leaves

Snowman adrift on a dystopia that could have been prevented if Jimmy had not

been seduced by his lack of awareness. This novel portrays Jimmy as a naďve,

superficial, hormone-driven male who does not see the impending doom right in

front of his eyes. These traits were created by the world within the Compounds

of spoiled, over-privileged children like Jimmy who only allow themselves to see

the world through rose-colored glasses. The beauty of Jimmy’s character is that

Atwood is writing a cultural criticism of superficiality, of our need for

constant entertainment, and consumerism that we (alongside Jimmy) ignore the

impending danger that comes with this type of thinking. Atwood does not shove

this ideology down your throat in an obvious manner; it simply comes while

reliving Jimmy’s tragic childhood and adulthood that we see the error of our

ways along with poor Jimmy. Weston is seen as a “broken” man who is searching

for something better when he visits Ecotopia and soon discovers their way of

life is what he was searching for all along. Weston is converted to a believer,

like Van and Jeff in Herland. When I was reading

Herland, I never got the impression

that alpha-male Terry would change his ways and live happily ever after in

utopia with the women of Herland. But I did see a change in Snowman when he was

recalling his memories but it was already too late for him. His journey took him

to the bad side of utopia, leaving him stranded only with his thoughts and the

innocent Crakers. Weston eventually leaves America for Ecotopia after

discovering the ease of living in a communal, free-loving society. All of these

examples provide readers an array of personalities who see life differently but

still experience the allure of utopia or the horror of dystopia.

Another interesting comparison between the novels exists within the

actual people themselves. For example, the women of Herland and the Crakers do

have a lot in common. When I was reading Herland, I thought that I would never

want to live with a colony of thousands of other women because women tend to be

harder on one another and competitive with each other. This idea struck me when

I read the book then found that Gilman’s women were painted in such a positive

light. The book was written in 1915 at a time when women were the embodiment of

purity, innocence, and motherhood but I saw it another way. I saw it as an

“imaginary” view of women from society’s pre-conceived notions about femininity

and the truth about women’s true nature. I do not know if it could qualify as

satire but I read the novel as an imaginary land where all women get along and

are happy which could not be further from the truth. The women are strong yet

feminine in their innocence, their appearance is uniform and boring but this

allows the men to see the differences by looking beyond their looks and getting

to know their real personalities (except for Terry).

In Oryx and Crake, the Crakers are

created to look uniform and aesthetically beautiful much like women would have

in 1915. Their nature is calm, innocent, and cooperative, much like women would

have been perceived in Herland. The two groups of utopians are mirroring

society’s views of the “perfect” person. However the women of Herland exist

without males and have been quite successful without them. The Crakers were

created to not have any human inhabitants after the “waterless flood” wiped them

all away. This void would have allowed the Crakers to coexist peacefully without

any human interaction that would infect their way of thinking. In Herland, I

believe the women may have viewed the absence of men in the same respect as

destroying their peaceful land with the essence of machismo that would

eventually ruin their paradise.

There are more positives than negatives when reading and learning about

Utopian Literature and branch out to many disciplines and other genres of

Literature. In my opinion, Utopian Literature is created “to mirror and confirm

social norms that oppose them” (Obj. 3a.). While teaching and learning about

Utopian Literature, this genre is valuable because it opens up the floor for

conversations that range from sociology, psychology, science, and religion.

Critics have argued that Speculative Fiction suffers from a genre-identity

crisis but I do not believe this is the case. SF melds Utopian/Dystopian

Literature with many other genres and proves valuable within a Literature course

as well as many other disciplines. Oryx

and Crake is a valuable in this seminar because it provides an example of

how Utopian Literature branches out to create new genres while entertaining and

educating its readers.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. Oryx and Crake. New

York: Anchor Books, 2003. Print.

---. “The Road to Ustopia.” The Guardian.

14 Oct. 2011. Web. 17 June 2013. (accessed from Dr. White’s LITR 5439 website).

Callenbach, Ernest. Ecotopia. New

York: Bantam Books, 1975. Print.

Gilman, Charlotte P. Herland. New

York: Dover, 1998. Print.

Horace. “Horace on Literature: ‘To Entertain & Inform.’” Web. 10 June 2013. (accessed from Dr. White’s LITR 5439 website).