|

LITR 4533: |

|

|

Video Highlight 2008 |

Tuesday, 17 June 2008:

Film / video presentation: (option 2: romance or romantic comedy): Andrea Drabek

Romantic Comedy

Romantic genre can go a variety of different ways

- Characters are usually separated from each other

- Separated from an object

- Or character needs rescuing

Most romance stories end with a “happily ever after”

Romantic comedies use the outline of romance with addition to using comedies problem or mistake guidelines

With the “happily ever after” ending the story will also resolve the problem or discover the true identity with a little slapstick

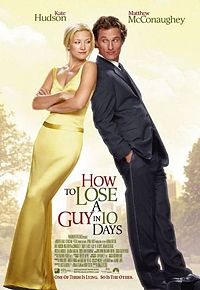

In “How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days” Andie and Ben are playing roles in a romantic comedy.

Andie, a journalist, is writing a how to article on how to lose a guy in 10 days. The guy chosen for her to experiment on, unbeknownst to her just made a deal he could make a woman fall in love with him in 10 days.

Questions:

1. What do you think will happen in the end after seeing the last two scenes?

2. Did you see any part of the clips that would represent a comical mistaken identity or problem?

3. In the end Andie and Ben end up together. According to the guidelines given for romance, do you think the ending would fall closer to a problem resolved, character being rescued, or reunited from separation?

from Genres Handout

Romance. This story may open as though all is well, but action usually begins with a problem of separation. Characters are separated from each other (e. g., a true-love romance), or a need arises to rescue someone (a lost-child story); or characters are separated from some object of desire (as with the search for the Holy Grail or Romancing the Stone or a lottery ticket). Action often takes the form of a physical journey or adventure; characters may be captured or threatened and rescued. Action may take the form of a personal transformation or a journey across class lines, as in Cinderella, Pretty Woman, or An Officer and a Gentleman. The conclusion of a romance narrative is typically “transcendence”—“getting away from it all” or “rising above it all.” The characters “live happily ever after” or “ride off into the sunset” or “fly away” from the scenes of their difficulties (in contrast with tragedy’s social engagement or comedy’s restored unity). . . .

Comedy. This story-line also often begins with a problem or a mistake (as in mistaken identity), but the problem is less significant than tragedy. The problem may involve a recognizable social situation, but unlike tragedy, the problem does not intimately threaten or shake the audience, the state, or the larger world. The problem often takes the form of mistaken or false identity: one person being taken for another, disguises, cross-dressing, dressing up or down. The action consists of characters trying to resolve the problem or live up to the demands of the false identity, or of other characters trying to reconcile the “new identity” with the “old identity.” Comedy ends with the problem overcome or the disguise abandoned. Usually the problem was simply “a misunderstanding” rather than a tragic error. The concluding action of a comedy is easy to identify. Characters join in marriage, song, dance, or a party, demonstrating a restoration of unity. (TV "situation comedies" like Friends or The Cosby Show end with the characters re-uniting in a living room or some other common space.) . . .