LITR 4332 American Minority Literature /

LITR 5731 Seminar in American Multicultural Literature

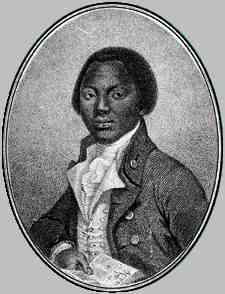

| classic slave narratives: selections from The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African by Olaudah Equiano (London, 1789) |

|

The following text is not a critical text for use in documented research. Rather, it adapts for American Minority Literature at University of Houston-Clear Lake an out-of-copyright transcription by Hanover Historical Texts Project.

To facilitate reading, changes include modernized spelling and division of long paragraphs. Bracketed annotations in small font are by instructor.

For reference in class, the paragraphs are indexed by chapter and number--see below. Such apparatus are not part of the original text; also recall that some paragraphs are divided from the original versions.

from Chapter 2: The author's birth and parentage--His being kidnapped with his sister--Their separation-surprise at meeting again--. . .

[ch. 2, par. 1] I hope the reader will not think I

have trespassed on his patience in introducing myself to him with some account

of the manners and customs of my country. They had been implanted in me with

great care, and made an impression on my mind, which time could not erase, and

which all the adversity and variety of fortune I have since experienced served

only to rivet and record; for, whether the love of one's country be real or

imaginary, or a lesson of reason, or an instinct of nature, I still look back

with pleasure on the first scenes of my life, though that pleasure has been for

the most part mingled with sorrow.

[ch. 2, par. 2] I have already acquainted the reader with the time and

place of my birth. My father, besides many slaves, had a numerous family, of

which seven lived to grow up, including myself and a sister, who was the only

daughter. As I was the youngest of the sons, I became, of course, the greatest

favourite with my mother, and was always with her; and she used to take

particular pains to form my mind. I was trained up from my earliest years in the

art of war; my daily exercise was shooting and throwing javelins; and my mother

adorned me with emblems, after the manner of our greatest warriors. In this way

I grew up till I was turned the age of eleven, when an end was put to my

happiness in the following manner.

[ch. 2, par. 3] Generally when the grown people in the neighborhood were

gone far in the fields to labour, the children assembled together in some of the

neighbors' premises to play; and commonly some of us used to get up a tree to

look out for any assailant, or kidnapper, that might come upon us; for they

sometimes took those opportunities of our parents absence to attack and carry

off as many as they could seize. One day, as I was watching at the top of a tree

in our yard, I saw one of those people come into the yard of our next neighbor

but one, to kidnap, there being many stout young people in it. Immediately on

this I gave the alarm of the rogue, and he was surrounded by the stoutest of

them, who entangled him with cords, so that he could not escape till some of the

grown people came and secured him.

[ch. 2, par. 4] But alas! ere long it was my fate to be thus attacked, and to be carried off, when none of the grown people were nigh. One day, when all our people were gone out to their works as usual, and only I and my dear sister were left to mind the house, two men and a woman got over our walls and in a moment seized us both, and, without giving us time to cry out, or make resistance, they stopped our mouths, and ran off with us into the nearest wood. Here they tied our hands, and continued to carry us as far as they could, till night came on, when we reached a small house where the robbers halted for refreshment, and spent the night. We were then unbound, but were unable to take any food; and, being quite overpowered by fatigue and grief, our only relief was some sleep, which allayed our misfortune for a short time.

[ch. 2, par. 5] The next morning we left the house,

and continued travelling all the day. For a long time we had kept the woods, but

at last we came into a road which I believed I knew. I had now some hopes of

being delivered; for we had advanced but a little way before I discovered some

people at a distance, on which I began to cry out for their assistance: but my

cries had no other effect than to make them tie me faster and stop my mouth, and

then they put me into a large sack. They also stopped my sister's mouth, and

tied her hands; and in this manner we proceeded till we were out of the sight of

these people. When we went to rest the following night they offered us some

victuals; but we refused it; and the only comfort we had was in being in one

another's arms all that night, and bathing each other with our tears. But alas!

we were soon deprived of even the small comfort of weeping together.

[ch. 2, par. 6] The next day proved a day of greater sorrow than I had

yet experienced; for my sister and I were then separated, while we lay clasped

in each other's arms. It was in vain that we besought them not to part us; she

was torn from me, and immediately carried away, while I was left in a state of

distraction not to be described. I cried and grieved continually; and for

several days I did not eat anything but what they forced into my mouth. At

length, after many days travelling, during which I had often changed masters I

got into the hands of a chieftain, in a very pleasant country. This man had two

wives and some children, and they all used me extremely well, and did all they

could to comfort me; particularly the first wife, who was something like my

mother. Although I was a great many days journey from my father's house, yet

these people spoke exactly the same language with us.

[ch. 2, par. 7] This first master of mine, as I may

call him, was a smith, and my principal employment was working his bellows,

which were the same kind as l had seen in my vicinity. They were in some

respects not unlike the stoves here in gentlemen's kitchens; and were covered

over with leather; and in the middle of that leather a stick was fixed and a

person stood up, and worked it, in the same manner as is done to pump water out

of a cask with a hand pump. I believe it was gold he worked, for it was of a

lovely bright yellow color, and was worn by the women on their wrists and

ankles. I was there I suppose about a month, and they at last used to trust me

some little distance from the house. This liberty I used in embracing every

opportunity to inquire the way to my own home: and I also sometimes, for the

same purpose, went with the maidens, in the cool of the evenings, to bring

pitchers of water from the springs for the use of the house. I had also remarked

where the sun rose in the morning, and set in the evening, as I had travelled

along; and I had observed that my father's house was towards the rising of the

sun. I therefore determined to seize the first opportunity of making my escape,

and to shape my course for that quarter; for I was quite oppressed and weighed

down by grief after my mother and friends; and my love of liberty, ever great,

was strengthened by the mortifying circumstance of not daring to eat with the

free-born children, although I was mostly their companion.

[ch. 2, par. 8] While I was projecting my escape, one day an unlucky

event happened, which quite disconcerted my plan, and put an end to my hopes. I

used to be sometimes employed in assisting an elderly woman slave to cook and

take care of the poultry; and one morning, while I was feeding some chickens, I

happened to toss a small pebble at one of them, which hit it on the middle and

directly killed it. The old slave having soon after missed the chicken, inquired

after it; and on my relating the accident (for I told her the truth, because my

mother world never suffer me to tell a lie) she flew into a violent passion,

threatened that I should suffer for it; and, my master being out, she

immediately went and told her mistress what I bad done. This alarmed me very

much, and I expected an instant flogging, which to me was uncommonly dreadful;

for I had seldom been beaten at home. I therefore resolved to fly; and

accordingly I ran into a thicket that was hard by, and hid myself in the bushes.

Soon afterwards my mistress and the slave returned, and, not seeing me, they

searched all the house, but not finding me, and I not making answer when they

called to me, they thought I had run away, and the whole neighborhood was raised

in the pursuit of me. In that part of the country (as in ours) the houses and

villages were skirted with woods, or shrubberies and the bushes were so thick

that a man could readily conceal himself in them, so as to elude the strictest

search.

[ch. 2, par. 9] The neighbors continued the whole

day looking for me, and several times many of them came within a few yards of

the place where I lay hid. I then gave myself up for lost entirely, and expected

every moment, when I heard a rustling among the trees, to be found out, and

punished by my master: but they never discovered me, though they were often so

near that I even heard their conjectures as they were looking about for me; and

I now learned from them, that any attempt to return home would be hopeless. Most

of them supposed I had fled towards home; but the distance was so great, and the

way so intricate, that they thought I could never reach it, and that I should be

lost in the woods. When I heard this I was seized with a violent panic, and

abandoned myself to despair. Night too began to approach, and aggravated all my

fears. I had before entertained hopes of getting home, and I had determined when

it should be dark to make the attempt; but I was now convinced it was fruitless,

and I began to consider that, if possibly I could escape all other animals, I

could not those of the human kind; and that, not knowing the way, I must perish

in the woods. . . .

[ch. 2, par. 10] I heard frequent rustlings among the leaves; and being

pretty sure they were snakes I expected every instant to be stung by them. This

increased my anguish and the horror of my situation became now quite

insupportable. I at length quitted the thicket, very faint and hungry, for I had

not eaten or drank anything all the day; and crept to my master's kitchen, from

whence I set out at first, and which was an open shed, and laid myself down in

the ashes with an anxious wish for death to relieve me from all my pains. I was

scarcely awake in the morning when the old woman slave who was the first up,

came to light the fire, and saw me in the fire place. She was very much

surprised to see me, and could scarcely believe her own eyes. She now promised

to intercede for me, and went for her master, who soon after came, and, having

slightly reprimanded me, ordered me to be taken care of, and not to be

ill-treated.

[ch. 2, par. 11] Soon after this my master's only daughter, and child by

his first wife, sickened and died, which affected him so much that for some time

he was almost frantic, and really would have killed himself, had he not been

watched and prevented. However, in a small time afterwards he recovered, and I

was again sold. I was now carried to the left of the sun's rising, through many

different countries, and a number of large woods. The people I was sold to used

to carry me very often, when I was tired, either on their shoulders or on their

backs. I saw many convenient well-built sheds along the roads, at proper

distances, to accommodate the merchants and travelers, who lay in those

buildings along with their wives, who often accompany them; and they always go

well armed.

[ch. 2, par. 12] From the time I left my own nation I always found

somebody that understood me till I came to the sea coast. The languages of

different nations did not totally differ, nor were they so copious as those of

the Europeans, particularly the English. They were therefore easily learned;

and, while I was journeying thus through Africa, I acquired two or three

different tongues. In this manner I had been travelling for a considerable time,

when one evening to my great surprise, whom should I see brought to the house

where I was but my dear sister! As soon as she saw me she gave a loud shriek,

and ran into my arms. I was quite overpowered: neither of us could speak; but,

for a considerable time, clung to each other in mutual embraces, unable to do

anything but weep. Our meeting affected all who saw us; and indeed I must

acknowledge, in honor of those fable destroyers of human rights, that I never

met with any ill treatment, or saw any offered to their slaves, except tying

them, when necessary, to keep them from running away. When these people knew we

were brother and sister they indulged us together; and the man, to whom I

supposed we belonged, lay with us, he in the middle, while she and I held one

another by the hands across his breast all night; and thus for a while we forgot

our misfortunes in the joy of being together: but even this small comfort was

soon to have an end; for scarcely had the fatal morning appeared, when she was

again torn from me forever! I was now more miserable, if possible, than before.

[ch. 2, par. 13] The small relief which her presence gave me from pain was gone, and the wretchedness of my situation was redoubled by my anxiety after her fate, and my apprehensions lest her sufferings should be greater than mine, when I could not be with her to alleviate them. Yes, thou dear partner of all my childish sports! Thou sharer of my joys and sorrows! happy should I have ever esteemed myself to encounter every misery for you, and to procure your freedom by the sacrifice of my own. Though you were early forced from my arms, your image has been always riveted in my heart, from which neither time nor fortune have been able to remove it; so that, while the thoughts of your sufferings have damped my prosperity, they have mingled with adversity and increased its bitterness. To that Heaven which protects the weak from the strong, I commit the care of your innocence and virtues, if they have not already received their full reward, and if your youth and delicacy have not long since fallen victims to the violence of the African trader, the pestilential stench of a Guinea ship, the seasoning in the European colonies, or the lash and lust of a brutal and unrelenting overseer.

[ch. 2, par. 14] I did not long remain after my sister. I was again sold, and carried through a number of places, till, after travelling a considerable time, I came to a town called Tinmah, in the most beautiful country I had yet seen in Africa. It was extremely rich, and there were many rivulets which flowed through it, and supplied a large pond in the center of the town, where the people washed. Here I first saw and tasted cocoa-nuts, which I thought superior to any nuts I had ever tasted before; and the trees, which were loaded, were also interspersed amongst the houses, which had commodious shades adjoining, and were in the same manner as ours, the insides being neatly plastered and whitewashed. Here I also saw and tasted for the first time sugar-cane. Their money consisted of little white shells, the size of the finger nail. I was sold here for one hundred and seventy-two of them by a merchant who lived and brought me there. I had been about two or three days at his house, when a wealthy widow, a neighbor of his, came there one evening, and brought with her an only son, a young gentleman about my own age and size. Here they saw me; and, having taken a fancy to me, I was bought of the merchant, and went home with them.

[ch. 2, par. 15] Her house and premises were

situated close to one of those rivulets I have mentioned, and were the finest I

ever saw in Africa: they were very extensive, and she had a number of slaves to

attend her. The next day I was washed and perfumed, and when meal-time came I

was led into the presence of my mistress, and ate and drink before her with her

son. This filled me with astonishment; and I could scarce help expressing my

surprise that the young gentleman should suffer me, who was bound, to eat with

him who was free; and not only so, but that he would not at any time either eat

or drink till I had taken first, because I was the eldest, which was agreeable

to our custom. Indeed everything here, and all their treatment of me, made me

forget that I was a slave. The language of these people resembled ours so

nearly, that we understood each other perfectly. They had also the very same

customs as we. There were likewise slaves daily to attend us, while my young

master and I with other boys sported with our darts and bows and arrows, as I

had been used to do at home. In this resemblance to my former happy state I

passed about two months; and I now began to think I was to be adopted into the

family, and was beginning to be reconciled to my situation, and to forget by

degrees my misfortunes when all at once the delusion vanished; for, without the

least previous knowledge, one morning early, while my dear master and companion

was still asleep, I was wakened out of my reverie to fresh sorrow, and hurried

away even amongst the uncircumcised.

[ch. 2, par. 16] Thus, at the very moment I dreamed of the greatest

happiness, I found myself most miserable; and it seemed as if fortune wished to

give me this taste of joy, only to render the reverse more poignant. The change

I now experienced was as painful as it was sudden and unexpected. It was a

change indeed from a state of bliss to a scene which is inexpressible by me, as

it discovered to me an element I had never before beheld, and till then had no

idea of, and wherein such instances of hardship and cruelty continually occurred

as I can never reflect on but with horror.

[ch. 2, par. 17] All the nations and people I had hitherto passed through

resembled our own in their manners, customs, and language: but I came at length

to a country, the inhabitants of which differed from us in all those

particulars. I was very much struck with this difference, especially when I came

among [a people who did not circumcise, and are without washing their

hands. They cooked also in iron pots, and had European cutlasses and cross bows,

which were unknown to us and fought with their fists amongst themselves. Their

women were not so modest as ours, for they ate, and drank, and slept, with their

men. But, above all, I was amazed to see no sacrifices or offerings among them.

In some of those places the people ornamented themselves with scars, and

likewise filed their teeth very sharp. They wanted sometimes to ornament me in

the same manner, but I would not suffer them; hoping that I might sometime be

among a people who did not thus disfigure themselves, as I thought they did.

[ch. 2, par. 18] At last I came to the banks of a

large river, which was covered with canoes, in which the people appeared to live

with their household utensils and provisions of all kinds. I was beyond measure

astonished at this, as I had never before seen any water larger than a pond or a

rivulet: and my surprise was mingled with no small fear when I was put into one

of these canoes, and we began to paddle and move along the river. We continued

going on thus till night; and when we came to land, and made fires on the banks,

each family by themselves some dragged their canoes on shore, others stayed and

cooked in theirs, and laid in them all night. Those on the land had mats, of

which they made tents, some in the shape of little houses: in these we slept and

after the morning meal we embarked again and proceeded as before. I was often

very much astonished to see some of the women, as well as the men, jump into the

water, dive to the bottom, come up again, and swim about.

[ch. 2, par. 19] Thus I continued to travel, sometimes by land, sometimes

by water, through different countries and various nations, till, at the end of

six or seven months after I had been kidnapped, I arrived at the sea coast. It

would be tedious and uninteresting to relate all the incidents which befell me

during this journey, and which I have not yet forgotten; of the various hands I

passed through, and the manners and customs of all the different people among

whom I lived: I shall therefore only observe, that in all the places where I was

the soil was exceedingly rich; the pomkins, eadas, plantains, yams, etc. etc.

were in great abundance, and of incredible size. There were also vast quantities

of different gums, though not used for any purpose, and everywhere a great deal

of tobacco. The cotton even grew quite wild; and there was plenty of red-wood. I

saw no mechanics whatever in all the way, except such as I have mentioned. The

chief employment in all these countries was agriculture, and both the males and

females, as with us were brought up to it, and trained in the arts of war.

[ch. 2, par. 1] The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on

the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and

waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon

converted into terror when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled and

tossed up to see if I were found by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded

that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill

me. Their complexions too differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the

language they spoke (which was very different from any I had ever heard), united

to confirm me in this belief. Indeed such were the horrors of my views and fears

at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own I would have freely

parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest

slave in my own country.

[ch. 2, par. 20] When I looked round the ship too

and saw a large furnace or copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of

every description chained together, everyone of their countenances expressing

dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and quite overpowered with

horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered

a little I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those

who brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in

order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by

those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair. They told me I

was not; and one of the crew brought me a small portion of spirituous liquor in

a wine glass; but, being afraid of him, I would not take it out of his hand. One

of the blacks therefore took it from him and gave it to me, and I took a little

down my palate, which, instead of reviving me, as they thought it would, threw

me into the greatest consternation at the strange feeling it produced having

never tasted any such liquor before. Soon after this the blacks who brought me

on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair.

[ch. 2, par. 21] I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to

my native country, or even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore which

I now considered as friendly; and I even wished for my former slavery in

preference to my present situation, which was filled with horrors of every kind,

still heightened by my ignorance of what I was to undergo. I was not long

suffered to indulge my grief; I was soon put down hinder the decks, and there I

received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life:

so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench and crying together, I became so

sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste

anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to

my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and on my refusing to eat,

one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across I think the windlass

and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. I had never experienced

anything of this kind before; and although, not being used to the water, I

naturally feared that element the first time I saw it, yet nevertheless, could I

have got over the nettings, I would have jumped over the side, but I could not;

and, besides, the crew used to watch us very closely who were not chained down

to the decks, lest we should leap into the water: and I have seen some of these

poor African prisoners most severely cut for attempting to do so, and hourly

whipped for not eating. This indeed was often the case with myself. In a little

time after, amongst the poor chained men, I found some of my own nation, which

in a small degree gave ease to my mind. I inquired of these what was to be done

with us; they gave me to understand we were to be carried to these white

people's country to work for them.

[ch. 2, par. 22] I then was a little revived, and thought, if it were no

worse than working, my situation was not so desperate: but still I feared I

should be put to death, the white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so

savage a manner; for I had never seen among any people such instances of brutal

cruelty; and this not only shown towards us blacks, but also to some of the

whites themselves. One white man in particular I saw, when we were permitted to

be on deck, flogged so unmercifully with a large rope near the foremast that he

died in consequence of it; and they tossed him over the side as they would have

done a brute. This made me fear these people the more; and I expected nothing

less than to be treated in the same manner. I could not help expressing my fears

and apprehensions to some of my countrymen: I asked them if these people had no

country, but lived in this hollow place (the ship): they told me they did not,

but came from a distant one. 'Then,' said I, 'how comes it in all our country we

never heard of them?' They told me because they lived so very far off. I then

asked where were their women? had they any like themselves? I was told they had:

'and why,' said I, 'do we not see them?' They answered, because they were left

behind. I asked how the vessel could go? They told me they could not tell; but

that there were cloths put upon the masts by the help of the ropes I saw, and

then the vessel went on; and the white men had some spell or magic they put in

the water when they liked in order to stop the vessel. I was exceedingly amazed

at this account, and really thought they were spirits. I therefore wished much

to be from amongst them, for I expected they would sacrifice me: but my wishes

were vain; for we were so quartered that it was impossible for any of us to make

our escape.

[ch. 2, par. 23] While we stayed on the coast I was mostly on deck; and

one day, to my great astonishment, I saw one of these vessels coming in with the

sails up. As soon as the whites saw it, they gave a great shout, at which we

were amazed; and the more so as the vessel appeared larger by approaching

nearer. At last she came to an anchor in my sight, and when the anchor was let

go I and my countrymen who saw it were lost in astonishment to observe the

vessel stop; and were now convinced it was done by magic. Soon after this the

other ship got her boats out, and they came on board of us, and the people of

both ships seemed very glad to see each other. Several of the strangers also

shook hands with US black people, and made motions with their bands, signifying

I suppose we were to go to their country; but we did not understand them. At

last, when the ship we were in had got in all her cargo, they made ready with

many fearful noises, and we were all put under deck, so that we could not see

how they managed the vessel. But this disappointment was the least of my sorrow.

The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so in tolerably loathsome,

that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been

permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship's

cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness

of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship,

which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost

suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became

unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a

sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the

improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers.

[ch. 2, par. 24] This wretched situation was again

aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth

of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost

suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the

whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself I was

soon reduced so low here that it was thought necessary to keep me almost always

on deck; and from my extreme youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I

expected every hour to share the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost

daily brought upon deck at the point of death, which I began to hope would soon

put an end to my miseries. Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep

much more happy than myself. I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as

often wished I could change my condition for theirs.

[ch. 2, par. 25] Every circumstance I met with served only to render my

state more painful, and heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty

of the whites. One day they had taken a number of fishes and when they had

killed and satisfied themselves with as many as they thought fit, to our

astonishment who were on the deck, rather than give any of them to us to eat as

we expected, they tossed the remaining fish into the sea again, although we

begged and prayed for some as well as we could, but in vain; and some of my

countrymen, being pressed by hunger, took an opportunity, when they thought no

one saw them, of trying to get a little privately; but they were discovered, and

the attempt procured them some very severe floggings. One day, when we had a

smooth sea and moderate wind, two of my wearied countrymen who were chained

together (I was near them at the time), preferring death to such a life of

misery, somehow made through the nettings and jumped into the sea: immediately

another quite dejected fellow, who, on account of his illness, was suffered to

be out of irons, also followed their example; and I believe many more would very

soon have done the same if they had not been prevented by the ship's crew, who

were instantly alarmed. Those of us that were the most active were in a moment

put down under the deck, and there was such a noise and confusion amongst the

people of the ship as I never heard before, to stop her, and get the boat out to

go after the slaves. However two of the wretches were drowned, but they got the

other, and afterwards flogged him unmercifully for thus attempting to prefer

death to slavery.

[ch. 2, par. 26] In this manner we continued to

undergo more hardships than I can now relate, hardships which are inseparable

from this accursed trade. Many a time we were near suffocation from the want of

fresh air, which we were often without for whole days together. This, and the

stench of the necessary tubs, carried off many. During our passage I first saw

flying fishes, which surprised me very much: they used frequently to fly across

the ship, and many of them fell on the deck. I also now first saw the use of the

quadrant; I had often with astonishment seen the mariners make observations with

it, and I could not think what it meant. They at last took notice of my surprise

and one of them, willing to increase it, as well as to gratify my curiosity made

me one day look through it. The clouds appeared to me to be land, which

disappeared as they passed along. This heightened my wonder; and I was now more

persuaded than ever that I was in another world, and that every thing about me

was magic.

[ch. 2, par. 27] At last we came in sight of the island of Barbadoes, at

which the whites on board gave a great shout, and made many signs of joy to us.

We did not know what to think of this; but as the vessel drew nearer we plainly

saw the harbor, and other ships of different kinds and sizes; and we soon

anchored amongst them off Bridge Town. Many merchants and planters now came on

board, though it was in the evening. They put us in separate parcels, and

examined us attentively. They also made us jump, and pointed to the land,

signifying we were to go there. We thought by this we should be eaten by those

ugly men, as they appeared to us; and, when soon after we were all put down

under the deck again, there was much dread and trembling among us, and nothing

but bitter cries to be heard all the night from these apprehensions, insomuch

that at last the white people got some old slaves from the land to pacify us.

They told us we were not to be eaten, but to work, and were soon to go on land,

where we should see many of our country people. This report eased us much; and

sure enough, soon after we were landed, there came to us Africans of all

languages. We were conducted immediately to the merchant's yard, where we were

all pent up together like so many sheep in a fold, without regard to sex or age.

[ch. 2, par. 28] As every object was new to me everything I saw filled me

with surprise. What struck me first was that the houses were built with stories,

and in every other respect different from those in Africa: but I was still more

astonished on seeing people on horseback. I did not know what this could mean;

and indeed I thought these people were full of nothing but magical arts. While I

was in this astonishment one of my fellow prisoners spoke to a countryman of his

about the horses, who said they were the same kind they had in their country. I

understood them, though they were from a distant part of Africa, and I thought

it odd I had not seen any horses there; but afterwards when I came to converse

with different Africans, I found they had many horses amongst them, and much

larger than those I then saw. We were not many days in the merchant's custody

before we were sold after their usual manner, which is this: On a signal given

(as the beat of a drum), the buyers rush at once into the yard where the slaves

are confined, and make choice of that parcel they like best. The noise and

clamor with which this is attended, and the eagerness visible in the

countenances of the buyers serve not a little to increase the apprehensions of

the terrified Africans, who may well be supposed to consider them as the

ministers of that destruction to which they think themselves devoted.

[ch. 2, par. 29] In this manner, without scruple, are relations and friends separated, most of them never to see each other again. I remember in the vessel in which I was brought over, in the men's apartment, there were several brothers, who, in the sale, were sold in different lots; and it was very moving on this occasion to see and hear their cries at parting. O, ye nominal Christians! might not an African ask you, learned you this from your God, who says unto you, Do unto all men as you would men should do unto you? Is it not enough that we are torn from our country and friends to toil for your luxury and lust of gain? Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice? Are the dearest friends and relations, now rendered more dear by their separation from their kindred, still to be parted from each other, and thus prevented from cheering the gloom of slavery with the small comfort of being together and mingling their sufferings and sorrows? Why are parents to lose their children, brothers their sisters, or husbands their wives? Surely this is a new refinement in cruelty, which, while it has no advantage to atone for it, thus aggravates distress, and adds fresh horrors even to the wretchedness of slavery.

from Chapter 3: The author is carried to

Virginia--His distress--Surprise at seeing a picture and a watch--. . .

[ch. 3, par. 1] I now totally lost the small remains of comfort I had

enjoyed in conversing with my countrymen; the women too, who used to wash and

take care of me, were all gone different ways, and I never saw one of them

afterwards.

[ch. 3, par. 2] I stayed in this island for a few days; I believe it

could not be above a fortnight; when I and some few more slaves, that were not

saleable amongst the rest, from very much fretting, were shipped off in a sloop

for North America. On the passage we were better treated than when we were

coming from Africa, and we had plenty of rice and fat pork. We were landed up a

river a good way from the sea, about Virginia county, where we saw few or none

of our native Africans, and not one soul who could talk to me. I was a few weeks

weeding grass, and gathering stones in a plantation; and at last all my

companions were distributed different ways, and only myself was left. I was now

exceedingly miserable, and thought myself worse off than any of the rest of my

companions; for they could talk to each other, but I had no person to speak to

that I could understand. In this state I was constantly grieving and pining, and

wishing for death rather than anything else.

[ch. 3, par. 3] While I was in this plantation the gentleman, to whom I

suppose the estate belonged, being unwell, I was one day sent for to his

dwelling house to fan him; when I came into the room where he was I was very

much affrighted at some things I saw, and the more so as I had seen a black

woman slave as I came through the house, who was cooking the dinner, and the

poor creature was cruelly loaded with various kinds of iron machines; she had

one particularly on her head, which locked her mouth so fast that she could

scarcely speak; and could not eat nor drink. I was much astonished and shocked

at this contrivance, which I afterward learned was called the iron muzzle. Soon

after I had a fan put into my hand, to fan the gentleman while he slept; and so

I did indeed with great fear.

[ch. 3, par. 4] While he was fast asleep I indulged

myself a great deal in looking about the room, which to me appeared very fine

and curious. The first object that engaged my attention was a watch which hung

on the chimney, and was going. I was quite surprised at the noise it made and

was afraid it would tell the gentleman anything I might do amiss: and when I

immediately after observed a picture hanging in the room, which appeared

constantly to look at me, I was still more affrighted, having never seen such

things as these before. At one time I thought it was something relative to

magic; and not seeing it move I thought it might be some way the whites had to

keep their great men when they died, and offer them libation as we used to do to

our friendly spirits. In this state of anxiety I remained till my master awoke,

when I was dismissed out of the room, to my no small satisfaction and relief;

for I thought that these people were all made up of wonders. In this place I was

called Jacob; but on board the African snow I was called Michael.

[ch. 3, par. 5] I had been some time in this miserable, forlorn, and much

dejected state, without having anyone to talk to, which made my life a burden,

when the kind and unknown hand of the Creator (who in very deed leads the blind

in a way they know not) now began to appear, to my comfort; for one day the

captain of a merchant ship, called the Industrious Bee, came on some business to

my master's house. This gentleman, whose name was Michael Henry Pascal, was a

lieutenant in the royal navy, but now commanded this trading ship, which was

somewhere in the confines of the county many miles off.

[ch. 3, par. 6] While he was at my master's house

it happened that he saw me, and liked me so well that he made a purchase of me.

I think I have often heard him say he gave thirty or forty pounds sterling for

me; but I do not now remember which. However, he meant me for a present to some

of his friends in England: and I was sent accordingly from the house of my then

master, one Mr. Campbell, to the place where the ship lay; I was conducted on

horseback by an elderly black man (a mode of travelling which appeared very odd

to me). When I arrived I was carried on board a fine large ship, loaded with

tobacco, etc. and just ready to sail for England. I now thought my condition

much mended; I had sails to lie on, and plenty of good vitals to eat; and

everybody on board used me very kindly, quite contrary to what I had seen of any

white people before; I therefore began to think that they were not all of the

same disposition. A few days after I was on board we sailed for England.

[ch. 3, par. 7] I was still at a loss to conjecture my destiny. By this

time, however, I could smatter a little imperfect English; and I wanted to know

as well as I could where we were going. Some of the people of the ship used to

tell me they were going to carry me back to my own country, and this made me

very happy. I was quite rejoiced at the sound of going back; and thought if I

should get home what wonders I should have to tell. But I was reserved for

another fate, and was soon undeceived when we came within sight of the

English coast. While I was on board this ship, my captain and master named me

Gustavus Vassa. I at that time began to understand him a little, and refused to

be called so, and told him as well as I could that I would be called Jacob; but

he said I should not, and still called me Gustavus; and when I refused to answer

to my new name, which at first I did, it gained me many a cuff; so at length I

submitted, and was obliged to bear the present name, by which I have been known

ever since.

[ch. 3, par. 8] The ship had a very long passage;

and on that account we had very short allowance of provisions. Towards the last

we had only one pound and a half of bread per week, and about the same quantity

of meat, and one quart of water a day. We spoke with only one vessel the whole

time we were at sea, and but once we caught a few fishes. In our extremities the

captain and people told me in jest they would kill and eat me; but I thought

them in earnest, and was depressed beyond measure, expecting every moment to be

my last. While I was in this situation one evening they caught with a good deal

of trouble, a large shark, and got it on board. This gladdened my poor heart

exceedingly, as I thought it would serve the people to eat instead of their

eating me; but very soon, to my astonishment, they cut off a small part of the

tail, and tossed the rest over the side. This renewed my consternation; and I

did not know what to think of these white people, though I very much feared they

would kill and eat me.

[ch. 3, par. 9] There was on board the ship a young lad who had never

been at sea before, about four or five years older than myself: his name was

Richard Baker. He was a native of America, had received an excellent education,

and was of a most amiable temper. Soon after I went on board he showed me a

great deal of partiality and attention, and in return I grew extremely fond of

him. We at length became inseparable; and, for the space of two years, he was of

very great use to me, and was my constant companion and instructor. Although

this dear youth had many slaves of his own, yet he and I have gone through many

sufferings together on shipboard; and we have many nights lain in each other's

bosoms when we were in great distress. Thus such a friendship was cemented

between us as we cherished till his death, which, to my very great sorrow,

happened in the year 1759, when he was up the Archipelago, on board his

majesty's ship the Preston: an event which I have never ceased to regret, as I

lost at once a kind interpreter, an agreeable companion, and a faithful friend;

who, at the age of fifteen, discovered a mind superior to prejudice; and who was

not ashamed to notice, to associate with, and to be the friend and instructor of

one who was ignorant, a stranger, of a different complexion, and a slave!

[ch. 3, par. 10] My master had lodged in his

mother's house in America: he respected him very much, and made him always eat

with him in the cabin. He used often to tell him jocularly that he would kill me

to eat. Sometimes he would say to me the black people were not good to eat, and

would ask me if we did not eat people in my country. I said, No: then he said he

would kill Dick (as he always called him) first, and afterwards me. Though this

nearing relieved my mind a little as to myself, I was alarmed for Dick and

whenever he was called I used to be very much afraid be was to be killed; and I

would peep and watch to see if they were going to kill him: nor was I free from

this consternation till we made the land.

[ch. 3, par. 11] One night we lost a man overboard; and the cries and

noise were so great and confused in stopping the ship, that I, who did not know

what was the matter, began, as usual, to be very much afraid, and to think they

were going to make an offering with me, and perform some magic; which I still

believed they dealt in. As the waves were very high I thought the Ruler of the

seas was angry, and I expected to be offered up to appease him. This filled my

mind with agony, and I could not any more that night close my eves again to

rest. However, when daylight appeared I was a little eased in my mind; but still

every time I was called I used to think it was to be killed. Sometime after this

we saw some very large fish, which I afterwards found were called grampuses

[killer whales or orcas]. They looked to me extremely terrible, and made their

appearance just at dusk and were so near as to blow the water on the ship's

deck. I believed them to be the rulers of the sea; and, as the white people did

not make any offerings at anytime, I thought they were angry with them: and, at

last, what confirmed my belief was, the wind just then died away, and a calm

ensued, and in consequence of it the ship stopped going.

[ch. 3, par. 12] I supposed that the fish had

performed this, and I hid myself in the fore part of the ship, through fear of

being offered up to appease them, every minute peeping and quaking: but my good

friend Dick came shortly towards me, and I took an opportunity to ask him, as

well as I could, what these fish were. Not being able to talk much English, I

could but just make him understand my question; and not at all, when I asked him

if any offerings were to be made to them: however, he told me these fish would

swallow anybody; which sufficiently alarmed me. Here he was called away by the

captain, who was leaning over the quarter-deck railing and looking at the fish;

and most of the people were busied in getting a barrel of pitch to light, for

them to play with. The captain now called me to him, having learned some of my

apprehensions from Dick ; and having diverted himself and others for some time

with my fears, which appeared ludicrous enough in my crying and trembling, he

dismissed me. The barrel of pitch was now lighted and put over the side into the

water: by this time it was just dark, and the fish went after it; and, to my

great joy, I saw them no more.

[ch. 3, par. 13] However, all my alarms began to subside when we got

sight of land; and at last the ship arrived at Falmouth, after a passage of

thirteen weeks. Every heart on board seemed gladdened on our reaching the shore,

and none more than mine. The captain immediately went on shore, and sent on

board some fresh provisions, which we wanted very much: we made good use of

them, and our famine was soon turned into feasting, almost without ending. It

was about the beginning of the spring 1757 when I arrived in England; and I was

nearly twelve years of age at that time. I was very much struck with the

buildings and the pavement of the streets in Falmouth; and, indeed, any object I

saw filled me with new surprise.

[ch. 3, par. 14] One morning when I got upon deck, I saw it covered all over with the snow that fell overnight: as I had never seen any thing of the kind before, I thought it was salt; so I immediately ran down to the mate and desired him, as well as I could, to come and see how somebody in the night had thrown salt all over the deck. He, knowing what it was, desired me to bring some of it down to him: accordingly I took up a handful of it, which I found very cold indeed; and when I brought it to him he desired me to taste it. I did so, and I was surprised beyond measure. I then asked him what it was; he told me it was snow: but I could not in anywise understand him. He asked me if we had no such thing in my country; and I told him, No. I then asked him the use of it, and who made it; he told me a great man in the heavens, called God: but here again I was to all intents and purposes at a loss to understand him; and the more so, when a little after I saw the air filled with it, in a heavy shower, which fell down on the same day.

[ch. 3, par. 15] After this I went to church; and

having never been at such a place before, I was again amazed at seeing and

hearing the service I asked all I could about it; and they gave me to understand

it was worshipping God, who made us and all things. I was still at a great loss,

and soon got into an endless field of inquiries, as well as I was able to speak

and ask about things. However, my little friend Dick used to be my best

interpreter; for I could make free with him, and he always instructed me with

pleasure: and from what I could understand by him of this God, and in seeing

these white people did not fell one another, as we did, I was much pleased; and

in this I thought they were much happier than we Africans. I was astonished at

the wisdom of the white people in all things I saw; but was amazed at their not

sacrificing, or making any offerings, and eating with unwashed hands, and

touching the dead. I likewise could not help remarking the particular

slenderness of their women, which I did not at first like; and I thought they

were not so modest and shamefaced as the African women.

[ch. 3, par. 16] I had often seen my master and Dick employed in reading;

and I had a great curiosity to talk to the books, as I thought they did; and so

to learn how all things had a beginning: for that purpose I have often taken up

a book, and have talked to it, and then put my ears to it, when alone, in hopes

it would answer me; and I have been very much concerned when I found it remained

silent.

[ch. 3, par. 17] My master lodged at the house of a gentleman in Falmouth, who had a fine little daughter about six or seven years of age, and she grew prodigiously fond of me; insomuch that we used to eat together, and had servants to wait on us. I was so much caressed by this family that it often reminded me of the treatment I had received from my little noble African master. After I had been here a few days, I was sent on board of the ship; but the child cried so much after me that nothing could pacify her till I was sent for again. It is ludicrous enough, that I began to fear I should be betrothed to this young lady; and when my master asked me if I would stay there with her behind him, as he was going away with the ship, which had taken in the tobacco again, I cried immediately, and said I would not leave her. At last, by stealth, one night I was sent on board the ship again; and in a little time we sailed for Guernsey, where she was in part owned by a merchant, one Nicholas Doberry.

[ch. 3, par. 18] As I was now amongst a people who

had not their faces scarred, like some of the African nations where I had been,

I was very glad I did not let them ornament me in that manner when I was with

them. When we arrived at Guernsey, my master placed me to board and lodge with

one of his mates, who had a wife and family there; and some months afterwards he

went to England, and left me in care of this mate, together with my friend Dick:

This mate had a little daughter, aged about five or six years, with whom I used

to be much delighted.

[ch. 3, par. 19] I had often observed that when her mother washed her

face it looked very rosy; but when she washed mine it did not look so: I

therefore tried often times myself if I could not by washing make my face of the

same colour as my little playmate (Mary), but it was all in vain; and I now

began to be mortified at the difference in our complexions. This woman behaved

to me with great kindness and attention; and taught me everything in the same

manner as she did her own child, and indeed in every respect treated me as such.

I remained here till the summer of the year 1757; when my master, being

appointed first lieutenant of his majesty's ship the Roebuck, sent for Dick and

me, and his old mate: on this we all left Guernsey, and set out for England in a

sloop bound for London. . . .