|

LITR 4332 American Minority Literature Model Assignments Research Project Submissions 2013 research journal |

|

Jasmine Summers

4/23/2013

The journey of the oral literature of

African-Americans and Native-American after contact with the now dominant

culture of America.

This research journal examines the

journey or evolution of the oral literature of the indigenous populations of

America, as well as of the Africans brought to American during the

trans-Atlantic slave trade before and after contact with Europeans.

It

will also examine any changes in oral tradition resulting from the meetings of

these two cultures and their intermarriages that created a new culture of the

Afro-Native American.

When people think of literature, the

first thing that usually comes to mind is great written works of art. Although

literature literally means “made from letters,” all literature is not written,

and if spoken, these unwritten works are considered to be oral literature. Oral

literature is defined as “any form of verbal art which is transmitted orally or

delivered by word of mouth”; it can consist of ballads, chants, folktales,

myths, creation stories, songs, legends, or proverbs to name a few. The practice

of oral literature is ancient and can be viewed as predating written literature.

In pre-literate societies, oral literature was the main means for transmitting

important cultural information throughout the generations. In some societies we

can even see that some written literature was directly transcribed from oral

literature such as the holy Hindu

Vedas, passed down orally for what some believe

to be thousands of years before being written down.

The research that I will conduct will focus on this form of

literature, but among the aforementioned cultural groups. I will focus on how

this form of literature changed or evolved due to significant and damaging

changes experienced by of these groups. Through my research, I plan to discover

how societal, environmental, and or cultural changes contributed to changes in

this style of literature, or if no changes were made at all.

Examination of oral traditions of Native Americans

pre-European Settlement

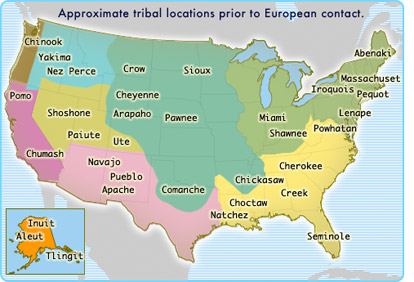

Although there were numerous indigenous

cultures with complex societies in America, I find that many of these tribes

have styles of oral literature that have many similar traits. Of all the

numerous Indian tribes, I chose to narrow down my field of research to the three

more well-known tribes that will hopefully have more information available. I

chose the Navajo, Iroquois, and Choctaw nations to focus on, as they are large

tribes that are still in existence today and from contrasting areas of the

United States.

Before the arrival of the Europeans to America many Native

American tribes lived in peace with small worries of food, shelter, inter-tribal

problems, and issues with other warring, enemy tribes. For some tribes, the

styles of oral literature at this time, before contact with Europeans, reflected

an overall tone of peace and connection with nature and the land.

As I mentioned before oral literature

is closely related to culture, and because of this it becomes part of oral

tradition. In American Indian tribes there is usually an elder or several

elders, whose responsibility is to pass on wisdom and the stories of their

ancestors to future generations so that this important information will never be

forgotten.

Common types of oral literature seen among many American

Indian tribes at this time period include:

-

Creation

Myths:

This style of oral literature was common among most all

tribes of America, as well as in most societies with strong oral histories and

gave a reason for the existence of the tribe and how they came to be.

-

Teleological

Myths:

Most tribes all had stories about how something important,

for example a food or animal that the tribe frequently used for sustenance may

also have a creation story. For example, the Choctaw tale of “Tanchi” explaining

how corn came to be.

-

Trickster

myths:

Trickster- a

deceptive, cunning character, oftentimes appearing as an animal, but can take on

many forms, and appears in many Native American myths”.

Many of the myths

involving the trickster

show

the figure as a cause of chaos and disorder. It is thought by some that the

trickster acts out human urges and desires, and is used as an example of what

may happen if one does a particular behavior, or acts a certain way. Many of the

Native American oral myths involving the trickster show this entity appearing as

the animals, rabbit and coyote.

I discovered that many of these tribes have trickster

myths, which interestingly enough, is widely seen in other cultures’ oral

literatures, specifically of West Africa. Although these cultures would merge

with each other in a few hundred years, it’s strange that both cultures, and

others, all unrelated at the time have such a strong similarity as far as these

myths are concerned. It makes me wonder where the “trickster myth” originated

since it seems to predate both of these cultures.

Common themes/elements of oral literature seen among many

American Indian tribes at this time period include:

-

Multiple Gods:

Native American tribes, similar to many indigenous nations,

were polytheistic. When researching Native American oral literature, one will

find references to many gods and goddesses, and usually the gods in these

stories are somehow tied to nature.

-

Animals/Nature:

Native America was a society of people that lived on and

from the land. They were very in touch with nature, and many times, their

beliefs and oral literature are concerned with animals of all types, as well as

aspects of nature. It is not uncommon for animals to speak and work on behalf of

the gods and humans, as well as the sun, moon, seasons, mountains, land, and

bodies of water to influence many of the oral literature of these tribes.

An example of some of the aforementioned styles of oral

literature:

Creation Myth: Iroquois

Long before the world was created there was an island,

floating in the sky, upon which the Sky People lived. They lived quietly and

happily. No one ever died or was born or experienced sadness. However one day

one of the Sky Women realized she was going to give birth to twins. She told her

husband, who flew into a rage. In the center of the island there was a tree

which gave light to the entire island since the sun hadn't been created yet. He

tore up this tree, creating a huge hole in the middle of the island. Curiously,

the woman peered into the hole. Far below she could see the waters that covered

the earth. At that moment her husband pushed her. She fell through the hole,

tumbling towards the waters below. Water animals already existed on the earth,

so far below the floating island two birds saw the Sky Woman fall. Just before

she reached the waters they caught her on their backs and brought her to the

other animals. Determined to help the woman they dove into the water to get mud

from the bottom of the seas. One after another the animals tried and failed.

Finally, Little Toad tried and when he reappeared his mouth was full of mud. The

animals took it and spread it on the back of Big Turtle. The mud began to grow

and grow and grow until it became the size of North America. Then the woman

stepped onto the land. She sprinkled dust into the air and created stars. Then

she created the moon and sun. The Sky Woman gave birth to twin sons. She named

one Sapling. He grew to be kind and gentle. She named the other Flint and his

heart was as cold as his name. They grew quickly and began filling the earth

with their creations. Sapling created what is good. He made animals that are

useful to humans. He made rivers that went two ways and into these he put fish

without bones. He made plants that people could eat easily. If he was able to do

all the work himself there would be no suffering. Flint destroyed much of

Sapling's work and created all that is bad. He made the rivers flow only in one

direction. He put bones in fish and thorns on berry bushes. He created winter,

but Sapling gave it life so that it could move to give way to Spring. He created

monsters which his brother drove beneath the Earth. Eventually Sapling and Flint

decided to fight till one conquered the other. Neither was able to win at first,

but finally Flint was beaten. Because he was a god Flint could not die, so he

was forced to live on Big Turtle's back. Occasionally his anger is felt in the

form of a volcano. The Iroquois people hold a great respect for all animals.

This is mirrored in their creation myth by the role the animals play. Without

the animals' help the Sky Woman may have sunk to the bottom of the sea and earth

may not have been created

Teleological myths:

The Story Of Tanchi-Choctaw

A long time ago, before there were grocery stores, two

Choctaw boys went hunting with bows and arrows. The two Choctaw boys hunted a

long time, but did not find a squirrel or deer to kill and eat. The boys did

shoot a blackbird. Then the Choctaw boys made a fire with sticks and cooked the

bird so they could eat it. When the bird was cooked, the two boys sat down on

the ground to eat. Before they could eat any of the bird, a woman came to them.

The woman said, "I am very hungry." The Choctaw boys were respectful so they

gave the bird to the woman and she ate it all up. The boys were still hungry,

but there was nothing left to eat. They did not tell the woman how hungry they

were. The woman said, "Thank you", and the boys said, "You're welcome." The

woman said, "Because you know how to share, I'm going to give you a surprise."

Then she told the boys to go home and to come back tomorrow. The next day, the

two Choctaw boys went back to the place where they gave the cooked bird to the

woman to eat. There, where the fire had been built, was something growing that

looked like a tree. The skinny tree had yellow things growing on it. The boys

did not know what the surprise was. They pulled off one of the yellow things and

smelled it. It smelled good. They ate some of it and it tasted good. "Let's take

this home and ask somebody what it is", the boys said. Mother didn't know what

it was. Father didn't know what it was. Nobody in the whole town knew what it

was, but they liked the way it tasted. Someone said, "What will we call this

delicious present the boys have shared with us?" The boys said, "Let's call it

tanchi."And the Choctaws still call the woman's present "tanchi" or corn.

The Story of the Mosquito-Oneida-Iroquois

A long, long

time ago, on the opposite shores of a river in Haudenosaunee country, two giant

mosquitoes came to rest. These mosquitoes were as big as a pine tree. As the

Haudenosaunee paddled down the river in their canoes, they were vulnerable to

attack by these hideous giant bugs. As the people passed by, the mosquitoes

swooped down and attacked the canoeists with their beaks, killing many. To avoid

these assaults, the Haudenosaunee, simply changed their route, avoiding this

river altogether. But it was to no avail. The mosquitoes moved to other venues

to seek their prey. These continued attacks caused great problems for the

Haudenosaunee, who used waterways as a main means of transportation. The people

never knew when or where they would be attacked and devoured by the creatures.

The Haudenosaunee had had enough. They formed a war party to find and destroy

the evil monster bugs. Two great canoes, filled with the bravest warriors, were

launched and sent to kill the beasts. The warriors were well armed for battle

with bows and arrows. Fastened to their belts were their war-clubs and knives.

They bravely went out to fight their foe. They did not have to travel far. After

paddling only a short distance down the river, the attack began. The beak of one

of the mosquitoes pierced one canoe, sinking its passengers. In retaliation, the

warriors in the second canoe, filled the air with arrows. The battle that ensued

was horrible. The warriors bravely fought on, but the mosquitoes seemed to be at

every turn. Within a short span of time more than half the warriors had been

killed. Those who remained were determined to die courageously. Leaving their

canoe, they planned to attack the creatures on the land. The warriors took cover

behind trees and bushes, surrounding the mosquitoes. The evil beings were unable

to retaliate, as they could not reach the warriors through the thick bushes. The

Haudenosaunee sprayed the air with their arrows, repeatedly piercing the flesh

of the creatures. As the battle raged on the warriors supply of arrows was

depleting. The mosquitoes, however, could resist no longer, and deeply wounded,

fell upon the ground. The warriors struck the beasts over and over with their

war clubs, until the mosquito’s bodies were torn to ruins. Suddenly, the air

filled with a swarm of tiny mosquitoes, buzzing about the warriors’ ears. These

tiny creatures had sprung forth from the blood of their huge predecessors, and

they, too, were fond of human blood. To this day, the tiny pests attack people

in retribution for the Haudenosaunee assault upon their ancestors.

Trickster Myth-Navajo

Ma'ii (the Trickster/coyote) was trotting along when he came

upon a prairie dog town. The prairie dogs started cursing and yelling at him and

Ma'ii got angry and prayed for it to rain, which it did, and Ma'ii was washed

away. Trickster came across Skunk and together they hatched a plan to get

revenge on the prairie dogs. Ma'ii told Skunk to tell the prairie dogs that he'd

died in the rainstorm. Ma'ii played dead and all the prairie dogs started

dancing around his body and clubbing him. As they were dancing and celebrating,

Skunk sprayed his stink into their eyes and Ma'ii jumped up and clubbed them all

to death, and cooked them in a fire pit. Then Ma'ii convinced Skunk to have a

footrace with him, to decide who would get to eat the prairie dogs. Ma'ii

started running, and Skunk hid behind a rock and doubled back and took the

prairie dogs and buried them. When Ma'ii returned, there were only four little

prairie dogs left in the fire pit. He flung them away in anger. Skunk was

sitting on a high perch, eating the prairie dogs, and dropping the bones onto

Ma'ii, who only got to chew the bones.

Examination of oral traditions of Native Americans

post-European Settlement throughout time period of Indian removal and

assimilation

The period of Indian removal and assimilation proved to be a

catastrophic time for many of the majority of existing indigenous tribes of the

time. Having their ancestral lands stolen from them and placed on reservations

or boarding schools had devastating effects. The tribal elders, in attempt to

maintain their cultural traditions and identities, continued to pass down the

same stories. The common types of literature of this time period were still

creation myths, teleological myths, and trickster myths, but one can see a

change in the overall tone, with sorrow incorporated into many of the stories.

Rather than original myths of creation, origins, myths, and gods, these same

stories started to largely include themes of sadness and loss of land and

identity. In addition to this change the attempts made to assimilate these

groups led to many of the tribes becoming literate in English, and we began to

see the evolution of oral literature into written literature in this culture.

Many Native American writers begun to use writing as a means to preserve oral

literature, for fear it would disappear during the disintegration of their

cultures during this time.

An example of the change of tone, and a

written excerpt of work by a Kiowan Native American,

N. Scott Momaday listed

below. Although he was born in the twentieth century, this particular work is a

great example of a story of culture, combined with the sorrow of the losses

suffered by his tribe:

From that moment, and so long as the legend lives, the Kiowas

have kinsmen in the night sky. Whatever they were in the mountains, they could

be no more. However tenuous their well-being, however much they had suffered and

would suffer again, they had found a way out of the wilderness.

My grandmother had a reverence for the sun, a holy regard

that now is all but gone out of mankind. There was a wariness in her, and an

ancient awe. She was a Christian in her later years, but she had come a long way

about, and she never forgot her birthright. As a child she had been to the Sun

Dances; she had taken part in those annual rites, and by them she had learned

the restoration of her people in the presence of Tai-me.

Examination of the evolution of oral literature of Native

Americans in modern time

Although oral literature has greatly

evolved into written literature within this culture, native Americans of today

from various tribes still hold onto many of the same traditions as their

ancestors, including oral traditions, or oral literature. Despite dealing with

the loss of identity, land, and culture, American Indians have worked hard to

preserve their cultures and customs. The 1960’s was a period of time when Native

American literature flourished and some refer to this period as the Native

American Renaissance where one can see more styles of writing, and literary

pieces taking on a tone of disdain at the treatment of America’s First People.

Before this time period, many writers focused on narratives, or autobiographies,

protest pieces, and novels. Today there are many authors and poets, which write

on a wide array of all topics, but one will find that many of the writings by

Native American authors today are largely related to their cultural identities.

Common styles of modern oral literature forms include:

Traditional storytelling and myths

Narratives and biographies

Novels

Just as the indigenous tribes of North America had elders,

the tribes in these areas of Africa also had elders. They too were considered

keepers of knowledge and preservers of culture. In this area of Africa the elder

was called a “griot” and was usually male. Oral literature was considered to be

a highly revered art form in this culture, and the role of the griot was

considered one of high prestige.

Common types of oral literature seen among many West African

tribes of this area at this time period include:

Creation Myths:

Many tribes from all over the continent of Africa have myths

on creation. These myths, like many other creation myths from societies all over

the world have the elements of gods and goddesses, along with aspects of nature.

Historical Narratives:

Details of historically significant

events throughout the histories of various tribes are also recounted as a part

of the oral literature of the culture. For example, in many of the West African

tribes I discovered that members of royalty were sometimes elevated to the

status of a god upon death. There are legends of the apotheosis of former kings

in many West African tribes.

Example: Shango, God of thunder and lightning.

Trickster Myths:

The tribes of West Africa, just like

many societies of the world have myths involving a trickster figure that usually

takes the form of an animal. Similar to Native American trickster myths, these

stories can be used to teach a moral lesson, or sometimes used simply for

entertainment. In most parts of Africa it has been determined that while the

rabbit is the animal found in most trickster myths of the continent, for West

Africa, the spider or tortoise will be the main animals involved, however many

animals are featured.

Common themes/elements of oral literature seen among many

American Indian tribes at this time period include:

-

Multiple Gods:

West African culture, like many Native Americans worshipped

multiple deities, and these gods and goddesses often played large roles in oral

literature

-

Animals/Nature

Again, very similar to Native American tribes, West Africans

oral literature is filled with all types of animals, ranging from rabbits,

spiders, and turtles, and some aspect of nature will almost always be included.

An example of some of the aforementioned styles of oral

literature:

Creating Myth: Yoruba

The entire world was filled with water when God decided to

create the world. God sent his messenger Obatala to perform the task of creating

the world. Obatala brought along his helper, a man named Oduduwa as well as a

calabash full of earth and a chicken. Then they began their descent to earth

from a rope. Along the way, they stopped over at a feast where Obatala got drunk

from drinking too much palm wine. Oduduwa, finding his master drunk, picked up

the calabash and the chicken and continued on the journey.

When Oduduwa reached the earth, he sprinkled earth from the calabash over the

water and he dropped the chicken on the earth. The chicken then ran around

spreading the earth in every direction he moved until there was land. Oduduwa

had now created earth from what used to be water. Later when Obatala got out of

his drunken haze, he discovered that Oduduwa had already performed his task and

he was very upset. God however gave him another task to perform – to create the

people that would populate the earth. And that was how the world was created in

a place now called Ile-Ife.

Historical narrative: Yoruba

Shango was the forth king of the ancient Oyo Empire, the West

African center of culture and politics for the Yoruba people. The Oyo Empire

thrived from the fifteenth century until 1835. Today, there are about 30 million

Yoruba people in West Africa, most in Nigeria. Shango was a powerful king, but

some of the people in the Oyo Empire thought he was unfair. When two of his

ministers challenged him for the throne, Shango fled into the forest. He

wandered in the forest for a long time and eventually hung himself from a tree.

After Shango died, his enemies' houses were set on fire, probably by Shango's

friends. But some people believed Shango had gone up into the heavens and was

sending fire down to Earth. That’s how Shango became known as the god of

thunder and

lightning. As the god of thunder and lightning, Shango has some powerful

energy. In artwork he is often depicted with a double ax on his head, the symbol

of a thunderbolt, or he is depicted as a fierce ram. Shango’s thunderous energy

became a symbol of the resistance of the Yoruba people during the 19th Century

when many Yoruba people were taken from Africa to the Americas as slaves.

Trickster

myths: Ashanti-Ghana

“Anansi was one of God's

chosen, and he lived in human form before he became a spider. One day he asked

God for a simple ear of corn, promising that he would repay God with one hundred

servants. God was always amused by the boastful and resourceful Anansi, and gave

him the ear of corn. Anansi set out with the ear and came to a village to rest.

He told the chief of the village that he had a sacred ear of corn from God and

needed both a place to sleep for the night and a safe place to keep the

treasure. The chief treated Anansi as an honored guest and gave him a

thatched-roof house to stay in, showing him a hiding place in the roof. During

the night, while the entire village was fast asleep, Anansi took the corn and

fed it to the chickens. The next morning Anansi woke the village with his cries.

"What happened to the sacred corn? Who stole it? Certainly God will bring great

punishment on this village!" He made such a fuss that the villagers begged him

to take a whole bushel of corn as a demonstration of their apologies. He then

set down the road with the bushel of corn until it grew too heavy for him to

carry. He then met a man on the road who had a chicken, and Anansi exchanged the

corn for the chicken. When Anansi arrived at the next village, he asked for a

place to stay and a safe place to keep the "sacred" chicken. In this new

village, Anansi was again treated as an honored guest, a great feast was held in

his honor, and he was shown a house to stay in and given a safe place for the

chicken. During the night Anansi butchered the chicken and smeared its blood and

feathers on the door of the chief's house. In the morning he woke everyone with

his cries, "The sacred chicken has been killed! Surely God will destroy this

village for allowing this to happen!" The frightened villagers begged Anansi to

take ten of their finest sheep as a token of their sincere apology. Anansi drove

the sheep down the road until he came to a group of men carrying a corpse. He

asked the men whose body they were carrying. The men answered that a traveler

had died in their village and they were bearing the body home for a proper

burial. Anansi then exchanged the sheep for the corpse and set out down the

road. At the next village, Anansi told the people that the corpse was a son of

God who was sleeping. He told them to be very quiet in order not to wake this

important guest. The people in this village, too, held a great feast and treated

Anansi as royalty. When morning came, Anansi told the villagers that he was

having a hard time waking the "son of God" from sleep, and he asked their help.

They started by beating drums, and the visitor remained asleep." Then they

banged pots and pans, but he was still "asleep." Then the villagers pounded on

the visitor's chest, and he still didn't stir. All of a sudden, Anansi cried

out, "You have killed him! You have killed a son of God! Oh, no! Certainly God

will destroy this whole village, if not the entire world!" The terrified

villagers then told Anansi that he could pick one hundred of their finest young

men as slaves if only he would appeal to God to save them. So Anansi returned to

God, having turned one ear of corn into one hundred slaves.”

Examination of oral traditions of African-Americans-post

trans-Atlantic Slave Trade into slavery in the southern United States.

The role of the storyteller changes during this time period.

What was once called the griot, is now usually an elder of a family and female.

During my research I came across a website titled “From griot to grandmother”,

which is a perfect way to describe the evolution of oral literature from West

Africa through the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and into slavery of the southern

US states. While examining the oral literature of this era, one can see that

many of the changes that occurred are a direct result of being placed into a new

society, and attempting to thrive under the destructive institution of slavery.

Rather than tribal members gathered around a fire, listening to the tribes’

griot retell stories of the ancient past of Africa, this era finds slaves

gathered around a maternal figure who would retell stories of their old country

after a long day’s work in the field. Although the common types of oral

literature during this era still consisted of the aforementioned styles of

creation stories, historical narratives, and trickster myths, this era begins to

show changes in some of the details of the original styles of literature.

For

example, the trickster myths

One can see how the trickster myths begin to evolve

and take on changes of the new settings and society. What was once the trickster

god Anansi, becomes “aunt nancy” in southern slave states and myths begin to

evolve to explain how these gods came to this new world.

An example of the variation of the trickster myth after West

African slaves reached the United Sates is listed below:

“Anansi walked for

many miles into the bush until he came upon some fresh tracks of a warthog. He

followed the tracks deep into the grassland. Sometime later he saw signs which

indicated that the warthog was not too far away. His mouth began to water. His

stomach started to grumble. He dreamed of sinking his teeth into juicy roasted

meat.

Upon reaching a patch of tall grass, Anansi saw the warthog

lying on its side. The warthog had been killed by someone else. However, there

was nobody around to claim it. "Ah, I wonder who was so kind to leave this meat

for me? Maybe it was my father Nyame the Sky God. Nyame must have seen that his

son was tired and hungry", Anansi thought to himself. "He took pity on me and

struck the beast down with his lightening so that I would not have to do the

hard work of killing it. I must thank Nyame." Anansi said.

Without giving thanks to Nyame, he quickly picked up some dry

sticks and made a fire. Soon the warthog was roasting. Before the roasted meat

had time to cool, Anansi began to eat. He did not stop eating until he had eaten

almost all of the meat, except for a piece of the foot.

Suddenly, Osebo the Leopard appeared out of the bushes

carrying some firewood, a large gourd filled with water, and a cooking pot. He

looked around for the warthog that he had killed. It was gone. However, in its

place was Anansi the Spider, stuffed and pleased.

The story continues when Osebo pursues Anansi who hides out

in a medicine bag around the neck of a captive woman on her wretched march into

slavery. Anansi is unwittingly transported on to a slave ship bound for the

Spanish Americas. During his perilous journey in the hold of the ship, he has an

encounter with Nyame. Anansi pleads with Nyame to return him home to Asanti.

However, Nyame has another plan for Anansi.

"I am sending you somewhere, Anansi, but not to Asanti. You

must go with these captives to the place called the New World." Nyame said.

"But, Nyame... These people are slaves! I did not have

anything to do with them being here.

They were the ones who brought me here. It is their misfortune to fall

into the hands of the slave traders. Oh, Nyame, punish the people who deal in

slavery... But send me back to my people." Anansi pleaded. Anansi was not sent

back to Asanti. Instead, he ended up in the New World. He arrived in Jamestown,

Virginia in 1619

against his will. There he became "The

Comforter of the Enslaved".:”

In addition to the changes of this

culture, new styles of oral literature begin to develop and take on important

meanings. The style of song begins to become a major component of this cultures’

literature. Through my research I have found that although Africa is very rich

in musical tradition, the songs of the slaves took on new meanings for this

group and their oral literature. Slave songs can be considered, as spirituals,

ballads, or work songs sung in the fields. These songs were used as a method of

preserving history of the people, making the work day go by faster, and as way

to vent frustrations of a miserable slave-life existence. The most interesting

and important reason for the use of song was to relay messages to other slaves

and to even help slaves escape to freedom.

In one website I came across, I found that in

Frederick Douglass’s autobiographical writings that he mentions these coded

songs, and clarifies for his readers that in many spirituals, when a slave sang

of life after death and making it to Heaven, that this was actually code for

escaping plantation owners, and reaching freedom in the North.

An example of how the oral tradition of song could be used to

help slaves reach freedom is listed below:

“Follow the Drinking Gourd”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pw6N_eTZP2U

–includes lyrics

This song was used by those involved with the Underground

Railroad. The title itself, “follow the drinking gourd” stands for the

constellation, the Big Dipper, which contains the North Star, this was a guide

for those traveling North the make their way to freedom.

At this time period there are many

changes in the styles and elements of the African descended slaves and their

oral literature, but we can see that one thing stayed the same; this form of

literature stayed largely oral until around the mid-eighteenth century due to it

being illegal for slaves to be educated, or taught to read and write. We can see

however through various slave narratives, such as Frederick Douglass’

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,

Booker T. Washington’s

Up from Slavery, that

education and literacy, was either offered to slaves by kind masters and

mistresses, or either acquired in secret. Much like some of the first written

narratives and stories by Native Americas, these stories have a tone of sorry

due to living such a miserable existence, but often strength and triumph as

well.

An example of a slave narrative, written by Booker Taliaferro

Washington is listed below:

|

I WAS born a slave on a plantation in Franklin

County, Virginia. I am not quite sure of the exact place or exact

date of my birth, but at any rate I suspect I must have been born

somewhere and at some time. As nearly as I have been able to learn,

I was born near a cross-roads post-office called Hale’s Ford, and

the year was 1858 or 1859. I do not know the month or the day. The

earliest impressions I can now recall are of the plantation and the

slave quarters—the latter being the part of the plantation where the

slaves had their cabins. |

|

|

My life had its beginning in the midst of the

most miserable, desolate, and discouraging surroundings. This was

so, however, not because my owners were especially cruel, for they

were not, as compared with many others. I was born in a typical log

cabin, about fourteen by sixteen feet square. In this cabin I lived

with my mother and a brother and sister till after the Civil War,

when we were all declared free. |

|

|

Of my ancestry I know almost nothing. In the

slave quarters, and even later, I heard whispered conversations

among the coloured people of the tortures which the slaves,

including, no doubt, my ancestors on my mother’s side, suffered in

the middle passage of the slave ship while being conveyed from

Africa to America. |

Examination of the evolution of oral literature of African

Americans in modern time

Oral literature that once used to consist of sitting around a

fire listening to a griot in West Africa, or to a grandmother on the plantation,

has now involved into something much more complex. Since the twentieth century,

oral literature evolved more into written literature with a plethora of authors

and poets creating vast ranges of literary works, but some parts of the

traditional styles of oral literature are still in existence, but in different

ways.

Common styles of modern oral literature forms include:

Hand-clap/Jumprope songs

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PtnTFj9xjKw

I actually used to do these handclap games as a kid and while

looking for an example of this game online, I could not locate the origin of

these games, but this clip takes place in Liberia, Africa. I now wonder if maybe

these children were taught this game by an outsider or if this is something that

actually may have originated in Africa, and if that is why it is so common for

African-American children to do for fun.

The Dozens

I have always heard of “the dozens”, and

heard people play “the dozens”, but was never aware of its sad historical

background in slavery. The dozens is defined as a “game” where one person spends

time cutting down the other person. It can also be considered a battle of

insults, for example, two people having the “yo momma” battle.

I discovered that this was indeed a contest played

among New Orleans slaves that were disfigured or dismembered for disobedience,

and were sold together in groups of a dozen. To help themselves deal with the

humiliation of being sold by the dozen, the slaves would have contests insulting

each other’s family, specifically each other’s mothers in order to practice

thickening their skins.

Toasting

Toasting is a long narrative about a specific character and

that character’s exploits that can last for hours in some instances. I have

personally sat through a toast giving by my uncle Otisee, that lasted for well

over and hour, nonstop.

Blues

This style was originated in the Deep South, and was usually

a narrative of sorrow and despair at the depressed existence of the

Black-American at the time. Although this is considered to be a musical genre,

blues takes its roots in the call and response forms of African music and

originated from the spirituals, and field songs of the slaves.

Rap music

Although this is a newer style of

oral literature, some may not consider it to be art or oral literature at all

due to it being sometimes controversial, but this genre is similar to blues and

the songs of the slaves in that all of these art forms reflect or reflected

social,

economic and political realities.

Examination of the evolution of oral literature of the

intermingling of the African-American and Native American cultures

For centuries, African

Americans and Native Americans have shared a culture that has not received much

recognition. It was not very long after Africans arrived to the US that they and

Native Americans being to intermarry and combine cultures. Unfortunately, I

cannot locate many resources on oral literature of these two groups at early

time periods, but as of now there are many written pieces of literature that

discuss the dual heritage of the groups. The main piece of oral literature that

I was able to come across was a fusion of both cultures’ trickster myths. The

famous Br’er Rabbit Tales are actually a mixture of both West African and Native

American trickster myths. Specifically the tales of

Br’er Rabbit and

the Tar Baby, Br’er Rabbit and the Turtle, and Br’er Rabbit Meets Coyote.

There are many pieces of written literature on African-Native American cultures,

especially works that are written more recently, but again, I did not locate

much oral literature from this group. A list of some of the books about and

written by African Native Americans is listed in the resource section.

Resources:

Books:

Walking the Choctaw Road

by: Tim Tingle

Choctaw tales

by: Mould, Tom

Diné Bahane': The Navajo Creation Story

Paul G. Zolbrod

Oneida Iroquois,

Folklore, Myth, and History: New York Oral Narrative from the Notes of H.E.

Allen and Others

The Native American Oral Tradition: Voices of the Spirit and

Soul

Lois J. Einhorn

The Way to Rainy Mountain

N. Scott Momaday

When Brer Rabbit Meets Coyote: AFRICAN-NATIVE AMERICAN

LITERATURE

Jonathan Brennan

Black Indian Slave Narratives

(Real Voices, Real History) (Real Voices, Real History Series)

Patrick Minges

IndiVisible: African-Native American Lives in the Americas

Gabrielle Tayac

(Editor)

William Loren Katz (Author)

The Trickster Comes West Pan-African

Influence in Early Black Diasporan Narrative

by:

Babacar M'Baye

Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears: A West African Tale

Verna Aardema

Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music (African

Expressive Cultures)

Thomas A. Hale

The Complete Collected Poems

of Maya Angelou

Maya

Angelou

The Spirituals and the Blues: An Interpretation

James H. Cone

Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary

America (Music Culture)

Tricia Rose

Liberating Voices: Oral Tradition in African American

Literature

Gayl Jones

African American Literature and the Classicist Tradition:

Black Women Writers from Wheatley to Morrison

Tracey L. Walters

Oral Folk Traditions in Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon:

African American History, Geneology and Cultural Identity

Szilvia Suranyi

Research/Citations

Websites:

http://www.balletaustin.org/education/documents/TOTFinal.pdf

http://www.indians.org/indigenous-peoples-literature.html

http://www.native-languages.org

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary

http://www.mythencyclopedia.com/Tr-Wa/Tricksters.html

http://westafrikanoralliterature.weebly.com/

http://web.mccsc.edu/~kmcglaun/mythology/african.htm

http://www.windows2universe.org/mythology/shango_storm.html

http://www.angelfire.com/stars3/magicrealms/africanfolk.html#t7

http://www.uncp.edu/home/hickss/taal/overview/index.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pw6N_eTZP2U

http://www.oneidaindiannation.com/culture/legends/26866234.html

http://nmai.si.edu/exhibitions/indivisible/introduction.html

http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/creole_art_african_am_oral.html

http://www.pbs.org/theblues/classroom/downloads/oral_tradition_the_blues.pdf

http://faculty.weber.edu/kmackay/native_american_literature.htm

http://ctl.du.edu/spirituals/Freedom/coded.cfm

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/wpa/index.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g9ZZFCIncA0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PtnTFj9xjKw

http://thedailyomnivore.net/2013/04/15/trickster/

http://www.balletaustin.org/education/documents/TOTFinal.pdf