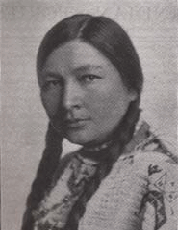

Zitkala-Sa, American Indian Stories

|

|

Midterm advice:

use course materials more (terms, objectives, texts; x-"you could have written this without taking the course")

improve writing: surface style, thematic organization and unity, content development

Discussion Questions:

Style Questions:

1. The first three selections from American Indian Stories are autobiographical sketches; the final two selections are more like fiction or short stories. How does the style change or not? How are nonfiction and fiction alike or different?

2. North American Indian cultures were almost exclusively oral or spoken cultures rather than written cultures like those of European-American settlers. Zitkala-Sa's early-life sketches depict an oral-spoken culture, while her experiences with missionaries and school show a written culture. How and where do the oral-spoken and written cultures appear? What different social structures do they entail? What strengths and limits to either? (Compare to 21st century USA and New World Order as "post-literate" society.)

Content Questions:

3. At what point(s) does she rewrite the Genesis Creation story to fit the Amerind story of loss and survival?

4. Broadly speaking, Zitkala-Sa grows up in a traditional culture, then moves into a modern culture. See Modern & Traditional Cultures. How does a traditional culture appear on the reservation; how does a modern culture appear at school; and how do the two types of culture conflict, adapt, or otherwise interact with each other? As another example, contrast the manners Zitkala-Sa is taught with the manners of the white people on the train. Also compare child-rearing attitudes.

4a. More broadly, how does minority literature help see the dominant culture differently? (Objective 7)

5. How are her experiences at school representative of problems in multicultural education? Consider the tension between modern institutions and traditional family structures.

Discussion Questions:

Style Questions:

1. The first three selections from American Indian Stories are autobiographical sketches; the final two selections are more like fiction or short stories. How does the style change or not? How are nonfiction and fiction alike or different?

third-person narrative (1st person can be fictional, but autobiography normally not 3rd person)

characters become more like types ("nephews" as tricksters)

symbolism more extravagant or deliberately focused (Statue of Liberty; papers)

DRM 5 symbols designed by the great "medicine man,"

DRM 7 The gift was a fantastic thing

DRM 7 a vision! A picture of an Indian camp

DRM 7 dream-stuff

DRM 7 real as life,—a circular camp of white cone-shaped tepees, astir with Indian people.

STAR 1 windshorn braids of white hair, log hut, tolerance of the land owner

2. North American Indian cultures were almost exclusively oral or spoken cultures rather than written cultures like those of European-American settlers. Zitkala-Sa's early-life sketches depict an oral-spoken culture, while her experiences with missionaries and school show a written culture. How and where do the oral-spoken and written cultures appear? What different social structures do they entail? What strengths and limits to either? (Compare to 21st century USA and New World Order as "post-literate" society.)

IMP 2.4-2.5 oral-spoken culture, legends, uncle's reputation

IMP 2.11 Iktomi story

IMP [2.12] Soothing my impatience, my mother said aloud, "My little daughter is anxious to hear your legends."

IMP 4.8 an old grandfather who had often told me Iktomi legends.

IMP [5.11] "Never pluck a single plum from this brush, my child, for its roots are wrapped around an Indian's skeleton. A brave is buried here. While he lived he was so fond of playing the game of striped plum seeds that, at his death, his set of plum seeds were buried in his hands. From them sprang up this little bush."

SCH IV. THE DEVIL.

SCH 4.1 legends the old warriors told me

SCH 4.2 a large book, picture of white man's devil

SCH 4.5 white man's papers

SCH 4.6 the Stories of the Bible

SCH 5.5 our daily records, iron routine, civilizing machine

SCH 5.6 the open pages of the white man's Bible. The dying Indian girl talked disconnectedly of Jesus the Christ

SCH 5.8 These sad memories rise above those of smoothly grinding school days. Perhaps my Indian nature is the moaning wind which stirs them now for their present record.

SCH 6.2 My mother had never gone inside of a schoolhouse, and so she was not capable of comforting her daughter who could read and write.

SCH [6.14] My mother was troubled by my unhappiness. Coming to my side, she offered me the only printed matter we had in our home. It was an Indian Bible, given her some years ago by a missionary. She tried to console me. "Here, my child, are the white man's papers. Read a little from them," she said most piously.

SCH 7.2 proud owner of my first diploma, college career against my mother's will

TCHR 2.1 a desk heaped up with work

TCHR 4.8 For the white man's papers

STAR 2 the white man's law, it was required of her to give proof of her membership in the Sioux tribe.

STAR 2 unwritten law of heart

STAR 4 lack of written records of a roving people

STAR 4 verbal reports of the old-time men and women of the tribe were varied,—some were actually contradictory.

STAR 35 he called his little granddaughter from her play, "You are my interpreter and scribe,"

STAR 40 the papers were made by two young Indian men who have learned the white man's ways.

STAR 41 folly of turning my letter into the hands of bureaucrats!

STAR 41 An inner voice said in his ear, "And this one letter will share the same fate of the other letters."

STAR 42 He could not go there with his letter.

STAR 43 he cast the letter into the flames. The fire consumed it. He sent his message on the wings of fire and he believed she would get it.

Content Questions:

3. At what point(s) does she rewrite the Genesis Creation story to fit the Amerind story of loss and survival?

VII. THE BIG RED APPLES.

IMP 7.1 first turning away

IMP 7.10 [As an inversion of the Genesis story, the missionaries and by proxy Judewin tempt the protagonist with forbidden fruit?]

IMP 7.17 [As in Genesis, the human protagonist listens to an outsider instead of listening to the parent or parental God]

4. Broadly speaking, Zitkala-Sa grows up in a traditional culture, then moves into a modern culture. See Modern & Traditional Cultures. How does a traditional culture appear on the reservation; how does a modern culture appear at school; and how do the two types of culture conflict, adapt, or otherwise interact with each other? As another example, contrast the manners Zitkala-Sa is taught with the manners of the white people on the train. Also compare child-rearing attitudes.

IMP 2.9 "What were they doing when you entered their tepee?" This taught me to remember all I saw at a single glance.

IMP 2.10 "What is your mother doing?"

IMP 3.3 mimesis

IMP 4.13 During this performance I felt conscious of being watched.

IMP 4.15 neither she nor the warrior, whom the law of our custom had compelled to partake of my insipid hospitality, said anything to embarrass me. They treated my best judgment, poor as it was, with the utmost respect.

IMP 5.3 a custom for young Indian women to invite some older relative to escort them to the public feasts. Though it was not an iron law, it was generally observed.

IMP 5.7] "My child, learn to wait. On our way to the celebration we are going to stop at Chanyu's wigwam. His aged mother-in-law is lying very ill, and I think she would like a taste of this small game."

IMP [6.11] Some missionaries gave me a little bag of marbles. They were all sizes and colors. Among them were some of colored glass. Walking with my mother to the river, on a late winter day, we found great chunks of ice piled all along the bank. The ice on the river was floating in huge pieces. As I stood beside one large block, I noticed for the first time the colors of the rainbow in the crystal ice. Immediately I thought of my glass marbles at home. With my bare fingers I tried to pick out some of the colors, for they seemed so near the surface. But my fingers began to sting with the intense cold, and I had to bite them hard to keep from crying.

IMP [6.12] From that day on, for many a moon, I believed that glass marbles had river ice inside of them.

SCH [1.3] On the train, fair women, with tottering babies on each arm, stopped their haste and scrutinized the children of absent mothers. Large men, with heavy bundles in their hands, halted near by, and riveted their glassy blue eyes upon us.

SCH 1.4 bold white faces

SCH 1.5 telegraph poles

SCH 6.9 I did not appreciate his kindly interest

SCH 6.12 They were no more young braves in blankets and eagle plumes, nor Indian maids with prettily painted cheeks. They had gone three years to school in the East, and had become civilized. The young men wore the white man's coat and trousers, with bright neckties. The girls wore tight muslin dresses, with ribbons at neck and waist. At these gatherings they talked English.

SCH 7.1 a secret interview with one of our best medicine men, bundle of magic roots

DRM 5 medicine bags

STAR 3 taught, for reasons now forgot, that an Indian should never pronounce his or her name in answer to any inquiry.

assimilation-resistance

IMP 7.23 She will need an education when she is grown, for then there will be fewer real Dakotas, and many more palefaces. This tearing her away, so young, from her mother is necessary, if I would have her an educated woman.

SCH 2.7 I resisted, tied in a chair

SCH 3.12 a rule which seemed needlessly binding

SCH 3.14 I whooped in my heart for having once asserted the rebellion within me.

SCH [7.3] I had written for her approval, but in her reply I found no encouragement. She called my notice to her neighbors' children, who had completed their education in three years. They had returned to their homes, and were then talking English with the frontier settlers. Her few words hinted that I had better give up my slow attempt to learn the white man's ways, and be content to roam over the prairies and find my living upon wild roots. I silenced her by deliberate disobedience.

SCH 7.4 I began anew my life among strangers.

SCH 7.5 a cold race whose hearts were frozen hard with prejudice.

SCH 7.7 my hands were tired from their weaving, the magic design which promised me the white man's respect.

SCH 7.11 smile when they wished to escort me in a procession to the students' parlor, where all were going to calm themselves. Thanking them for the kind spirit which prompted them to make such a proposition, I walked alone with the night to my own little room.

SCH 7.14 a large white flag, with a drawing of a most forlorn Indian girl on it. Under this they had printed in bold black letters words that ridiculed the college which was represented by a "squaw."

SCH 7.17 The evil spirit laughed within me when the white flag dropped out of sight, and the hands which hurled it hung limp in defeat.

SCH 7.18 soon in my room.

TCHR 1.1 she would have said the white man's papers were not worth the freedom and health I had lost by them.

TCHR 4.6 In the process of my education I had lost all consciousness of the nature world about me.

TCHR 4.8 Like a slender tree, I had been uprooted from my mother, nature, and God.

TCHR 4.9 Now a cold bare pole I seemed to be, planted in a strange earth.

TCHR 4.10 I resigned my position as teacher; and now I am in an Eastern city . . . Now, as I look back upon the recent past, I see it from a distance, as a whole.

TCHR 4.12 few there are who have paused to question whether real life or long-lasting death lies beneath this semblance of civilization.

DRM 3 When his small granddaughter grew up she learned the white man's tongue, and followed in the footsteps of her grandfather to the very seat of government to carry on his humanitarian work.

STAR 7 The coffee habit was one of the signs of her progress in the white man's civilization

STAR 7 from the tepee into a log hut, another achievement.

STAR 7 learned to read the primer and to write her name. Little Blue-Star attended school

STAR 47 The superintendent says you are one of the bad Indians, singing war songs and opposing the government all the time

4a. More broadly, how does minority literature help see the dominant culture differently? (Objective 7)

SCH 7.5 a cold race whose hearts were frozen hard with prejudice.

SCH 7.11 smile when they wished to escort me in a procession to the students' parlor, where all were going to calm themselves. Thanking them for the kind spirit which prompted them to make such a proposition, I walked alone with the night to my own little room.

SCH 7.18 soon in my room.

TCHR 1.5 my room,—a small, carpeted room

TCHR 1.6 a stately gray-haired man

TCHR 2.20 this village has been these many winters a refuge for white robbers.

TCHR 3.1 the shrinking limits of the village. She told me about the poverty-stricken white settlers, who lived in caves dug in the long ravines of the high hills across the river.

TCHR 3.2 A whole tribe of broad-footed white beggars had rushed hither to make claims on those wild lands.

TCHR 3.3 more and more twinkling lights,

TCHR 3.4 this same paleface who offers in one palm the holy papers, and with the other gives a holy baptism of firewater.

TCHR 4.7 alone in my room

TCHR 4.12 few there are who have paused to question whether real life or long-lasting death lies beneath this semblance of civilization.

5. How are her experiences at school representative of problems in multicultural education? Consider the tension between modern institutions and traditional family structures.

SCH 1.9 strong glaring light, large whitewashed room, harsh noise, woman tosses up

SCH 2.1 loud metallic voice, clatter of shoes

SCH 2.2 immodestly dressed

SCH 2.3 Among our people, short hair was worn by mourners, and shingled hair by cowards!

SCH 2.6 squeaking shoes, crawled under bed

SCH 2.8 cold blades, lost my spirit, Not a soul reasoned quietly with me, as my own mother used to do; for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder.

loss and survival

IMP 1.11 the hill where my uncle and my only sister lay buried.

IMP [I.12] "There is what the paleface has done! Since then your father too has been buried in a hill nearer the rising sun. We were once very happy. But the paleface has stolen our lands and driven us hither.

TCHR 1.2 work for the Indian race, teach in an Eastern Indian school

DRM 3 When his small granddaughter grew up she learned the white man's tongue, and followed in the footsteps of her grandfather to the very seat of government to carry on his humanitarian work.

DRM 8 "Be glad! Rejoice! Look up, and see the new day dawning! Help is near! Hear me, every one."

STAR 56 singing native songs of joy for the safe return to them of their absent one.

STAR 57 Blue-Star Woman's two nephews.

6. Discuss Blue Star Woman's two "nephews" as trickster figures.

STAR 12 footfall of two Indian men

STAR 13 short-cropped hair, faded civilian clothes, white man's shoes

STAR 13 "Pray, who are these would-be white men?" she inquired.

STAR 14 these near white men speak my native tongue and shake hands according to our custom."

STAR 17 we are educated in the white man's ways

notes for Zitkala-Sa, American Indian Stories

I. MY MOTHER

1.1 wigwam, Missouri River

1.2 mother sad, silent, hard bitter lines, tears

1.4 wild little girl, free as the wind

She taught me no fear save that of intruding myself upon others.

1.5 I was not wholly conscious of myself, but was more keenly alive to the fire within. It was as if I were the activity, and my hands and feet were only experiments for my spirit to work upon.

1.6 I admired my cousin greatly. So I said: "Mother, when I am tall as my cousin Warca-Ziwin, you shall not have to come for water. I will do it for you."

1.7 "If the paleface does not take away from us the river we drink."

[I.9] "My little daughter, he is a sham,—a sickly sham! The bronzed Dakota is the only real man."

1.11 the hill where my uncle and my only sister lay buried.

[I.12] "There is what the paleface has done! Since then your father too has been buried in a hill nearer the rising sun. We were once very happy. But the paleface has stolen our lands and driven us hither.

1.13 driven, my child, driven like a herd of buffalo

the Great Spirit had forgotten us!

II. THE LEGENDS.

2.4-2.5 oral-spoken culture, legends, uncle's reputation

2.5 observe this very proper silence, a sensing of the atmosphere

[2.6] The old folks knew the meaning of my pauses; and often they coaxed my confidence by asking, "What do you seek, little granddaughter?"

2.9 "What were they doing when you entered their tepee?" This taught me to remember all I saw at a single glance.

2.10 "What is your mother doing?"

2.11 Iktomi story

[2.12] Soothing my impatience, my mother said aloud, "My little daughter is anxious to hear your legends."

2.13 the old women made funny remarks

[2.14] The distant howling of a pack of wolves or the hooting of an owl in the river bottom frightened me

[2.15] On such an evening, I remember the glare of the fire shone on a tattooed star upon the brow of the old warrior who was telling a story. I watched him curiously as he made his unconscious gestures. The blue star upon his bronzed forehead was a puzzle to me. Looking about, I saw two parallel lines on the chin of one of the old women. The rest had none. I examined my mother's face, but found no sign there.

2.17 secret signs

III. THE BEADWORK.

3.1 dwelling opens to nature

3.2 beads cf. palette; I felt the envious eyes of my playmates upon the pretty red beads decorating my feet.

3.3 mimesis

IV. THE COFFEE-MAKING.

4.2 a tall, broad-shouldered crazy man, some forty years old, who walked loose among the hills. Wiyaka-Napbina (Wearer of a Feather Necklace)

4.3 the belief that an evil spirit was haunting his steps; such a silly big man

[4.4] "Pity the man, my child. I knew him when he was a brave and handsome youth. He was overtaken by a malicious spirit among the hills, one day, when he went hither and thither after his ponies. Since then he can not stay away from the hills," she said.

4.8 an old grandfather who had often told me Iktomi legends.

4.13 During this performance I felt conscious of being watched.

4.15 neither she nor the warrior, whom the law of our custom had compelled to partake of my insipid hospitality, said anything to embarrass me. They treated my best judgment, poor as it was, with the utmost respect.

V. THE DEAD MAN'S PLUM BUSH.

5.1-5.5 feast to recognize warrior's successes

5.3 a custom for young Indian women to invite some older relative to escort them to the public feasts. Though it was not an iron law, it was generally observed.

[5.7] "My child, learn to wait. On our way to the celebration we are going to stop at Chanyu's wigwam. His aged mother-in-law is lying very ill, and I think she would like a taste of this small game."

5.8 momentary shame

[5.11] "Never pluck a single plum from this brush, my child, for its roots are wrapped around an Indian's skeleton. A brave is buried here. While he lived he was so fond of playing the game of striped plum seeds that, at his death, his set of plum seeds were buried in his hands. From them sprang up this little bush."

5.12 forbidden fruit, sacred ground

VI. THE GROUND SQUIRREL.

6.1 older aunt, jovial and less reserved

6.2 string of large blue beads around her neck,—beads that were precious because my uncle had given them

6.4 the sacred hour when a misty smoke hung over a pit surrounded by an impassable sinking mire.

[6.6] From a field in the fertile river bottom my mother and aunt gathered an abundant supply of corn. Near our tepee they spread a large canvas upon the grass, and dried their sweet corn in it. I was left to watch the corn, that nothing should disturb it. I played around it with dolls made of ears of corn. I braided their soft fine silk for hair, and gave them blankets as various as the scraps I found in my mother's workbag.

[6.8] When mother had dried all the corn she wished, then she sliced great pumpkins into thin rings; and these she doubled and linked together into long chains. She hung them on a pole that stretched between two forked posts. The wind and sun soon thoroughly dried the chains of pumpkin. Then she packed them away in a case of thick and stiff buckskin.

[6.11] Some missionaries gave me a little bag of marbles. They were all sizes and colors. Among them were some of colored glass. Walking with my mother to the river, on a late winter day, we found great chunks of ice piled all along the bank. The ice on the river was floating in huge pieces. As I stood beside one large block, I noticed for the first time the colors of the rainbow in the crystal ice. Immediately I thought of my glass marbles at home. With my bare fingers I tried to pick out some of the colors, for they seemed so near the surface. But my fingers began to sting with the intense cold, and I had to bite them hard to keep from crying.

[6.12] From that day on, for many a moon, I believed that glass marbles had river ice inside of them.

VII. THE BIG RED APPLES.

7.1 first turning away

7.2 they had come to take away Indian boys and girls to the East.

[7.3] "Mother, my friend Judewin is going home with the missionaries. She is going to a more beautiful country than ours;

7.4 my big brother Dawee had returned from a three years' education in the East,

buffalo skin > canvas > cabin of logs

7.7 the Wonderland

7.9 not yet an ambition for Letters that was stirring me.

7.10 [As an inversion of the Genesis story, the missionaries and by proxy Judewin tempt the protagonist with forbidden fruit?]

7.17 [As in Genesis, the human protagonist listens to an outsider instead of listening to the parent or parental God]

7.23 She will need an education when she is grown, for then there will be fewer real Dakotas, and many more palefaces. This tearing her away, so young, from her mother is necessary, if I would have her an educated woman.

THE SCHOOL DAYS OF AN INDIAN GIRL

I. THE LAND OF RED APPLES

1.2 Red Apple Country; throngs of staring palefaces

[1.3] On the train, fair women, with tottering babies on each arm, stopped their haste and scrutinized the children of absent mothers. Large men, with heavy bundles in their hands, halted near by, and riveted their glassy blue eyes upon us.

1.4 bold white faces

1.5 telegraph poles

1.9 strong glaring light, large whitewashed room, harsh noise, woman tosses up

II. THE CUTTING OF MY LONG HAIR.

2.1 loud metallic voice, clatter of shoes

2.2 immodestly dressed

2.3 Among our people, short hair was worn by mourners, and shingled hair by cowards!

2.6 squeaking shoes, crawled under bed

2.7 I resisted, tied in a chair

2.8 cold blades, lost my spirit, Not a soul reasoned quietly with me, as my own mother used to do; for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder.

III. THE SNOW EPISODE.

3.1 shrill voice, imperative hand

3.4 severe tones

3.7 a hard spanking

3.12 broken English

3.12 a rule which seemed needlessly binding

3.14 I whooped in my heart for having once asserted the rebellion within me.

IV. THE DEVIL.

4.1 legends the old warriors told me

4.2 a large book, picture of white man's devil

4.5 white man's papers

4.6 the Stories of the Bible

V. IRON ROUTINE

5.1 loud-clamoring bell

5.5 our daily records, iron routine, civilizing machine

5.6 the open pages of the white man's Bible. The dying Indian girl talked disconnectedly of Jesus the Christ

5.7 actively testing the chains which tightly bound my individuality like a mummy for burial.

5.8 These sad memories rise above those of smoothly grinding school days. Perhaps my Indian nature is the moaning wind which stirs them now for their present record.

VI. FOUR STRANGE SUMMERS.

6.2 My mother had never gone inside of a schoolhouse, and so she was not capable of comforting her daughter who could read and write.

6.5 pony ride

6.9 I did not appreciate his kindly interest

6.12 They were no more young braves in blankets and eagle plumes, nor Indian maids with prettily painted cheeks. They had gone three years to school in the East, and had become civilized. The young men wore the white man's coat and trousers, with bright neckties. The girls wore tight muslin dresses, with ribbons at neck and waist. At these gatherings they talked English.

[6.14] My mother was troubled by my unhappiness. Coming to my side, she offered me the only printed matter we had in our home. It was an Indian Bible, given her some years ago by a missionary. She tried to console me. "Here, my child, are the white man's papers. Read a little from them," she said most piously.

6.17 my mother's voice wailing among the barren hills which held the bones of buried warriors. She called aloud for her brothers' spirits

6.19 drove me away to the eastern school. I rode on the white man's iron steed,

VII. INCURRING MY MOTHER'S DISPLEASURE.

7.1 a secret interview with one of our best medicine men, bundle of magic roots

7.2 proud owner of my first diploma, college career against my mother's will

7.4 I began anew my life among strangers.

7.5 a cold race whose hearts were frozen hard with prejudice.

7.7 my hands were tired from their weaving, the magic design which promised me the white man's respect.

7.8 an oratorical contest

7.10 bouquet of roses

7.11 first place

7.11 smile when they wished to escort me in a procession to the students' parlor, where all were going to calm themselves. Thanking them for the kind spirit which prompted them to make such a proposition, I walked alone with the night to my own little room.

7.12 college representative in another contest.

7.13 strong prejudice against my people.

7.14 a large white flag, with a drawing of a most forlorn Indian girl on it. Under this they had printed in bold black letters words that ridiculed the college which was represented by a "squaw."

7.17 The evil spirit laughed within me when the white flag dropped out of sight, and the hands which hurled it hung limp in defeat.

7.18 soon in my room.

AN INDIAN TEACHER AMONG INDIANS

I. MY FIRST DAY

1.1 she would have said the white man's papers were not worth the freedom and health I had lost by them.

1.2 work for the Indian race, teach in an Eastern Indian school

1.3 an old-fashioned town,

1.4 a quaint little village

1.5 my room,—a small, carpeted room

1.6 a stately gray-haired man

II. A TRIP WESTWARD.

2.1 a desk heaped up with work

2.5 A strong hot wind seemed determined to blow my hat off, and return me to olden days when I roamed bareheaded over the hills.

2.5 a trusty driver, whose unkempt flaxen hair hung shaggy about his ears and his leather neck of reddish tan. From accident or decay he had lost one of his long front teeth.

2.7 cone-shaped wigwam

2.8 a large yellow acre of wild sunflowers. Just beyond this nature's garden we drew near to my mother's cottage. Close by the log cabin stood a little canvas-covered wigwam.

[2.11] "My daughter, what madness possessed you to bring home such a fellow?"

[2.13] a brisk fire on the ground in the tepee, This light luncheon she brought into the cabin, and arranged on a table covered with a checkered oilcloth.

2.14 My mother had never gone to school, and though she meant always to give up her own customs for such of the white man's ways as pleased her, she made only compromises.

2.14 the peculiar odor that I could not forget.

2.16 Your brother Dawee, too, has lost his position,

[2.17] Dawee was a government clerk in our reservation; the Great Father at Washington sent a white son to take your brother's pen from him?

2.20 this village has been these many winters a refuge for white robbers.

2.22 praying steadfastly to the Great Spirit to avenge our wrongs

III. MY MOTHER'S CURSE UPON WHITE SETTLERS.

3.1 the shrinking limits of the village. She told me about the poverty-stricken white settlers, who lived in caves dug in the long ravines of the high hills across the river.

3.2 A whole tribe of broad-footed white beggars had rushed hither to make claims on those wild lands.

3.3 more and more twinkling lights,

3.4 this same paleface who offers in one palm the holy papers, and with the other gives a holy baptism of firewater.

IV. RETROSPECTION.

4.1 large army of white teachers in Indian schools had a larger missionary creed

4.2 self-preservation

4.4 a man was sent from the Great Father to inspect Indian schools

4.5 in no mood to strain my eyes in searching for latent good in my white co-workers.

4.6 In the process of my education I had lost all consciousness of the nature world about me.

4.7 alone in my room

4.8 For the white man's papers

4.8 Like a slender tree, I had been uprooted from my mother, nature, and God.

4.9 Now a cold bare pole I seemed to be, planted in a strange earth.

4.10 I resigned my position as teacher; and now I am in an Eastern city . . . Now, as I look back upon the recent past, I see it from a distance, as a whole.

4.12 few there are who have paused to question whether real life or long-lasting death lies beneath this semblance of civilization.

A DREAM OF HER GRANDFATHER

3 When his small granddaughter grew up she learned the white man's tongue, and followed in the footsteps of her grandfather to the very seat of government to carry on his humanitarian work.

3 a strange dream one night during her stay in Washington.

3 clean, strong and durable in its native genuineness

5 her childhood days and the stories she loved to hear a

5 medicine bags

5 symbols designed by the great "medicine man,"

5 never made for relics.

6 disappointment, seeing no beaded Indian regalia or trinkets.

7 The gift was a fantastic thing

7 a vision! A picture of an Indian camp

7 dream-stuff

7 real as life,—a circular camp of white cone-shaped tepees, astir with Indian people.

8 "Be glad! Rejoice! Look up, and see the new day dawning! Help is near! Hear me, every one."

THE WIDESPREAD ENIGMA CONCERNING BLUE-STAR WOMAN

1 windshorn braids of white hair, log hut, tolerance of the land owner

2 the white man's law, it was required of her to give proof of her membership in the Sioux tribe.

2 unwritten law of heart

2 A piece of earth is my birthright."

3 taught, for reasons now forgot, that an Indian should never pronounce his or her name in answer to any inquiry.

3 Blue-Star Woman lived in times when this teaching was disregarded.

3 government official: Who were your parents?

4 lack of written records of a roving people

4 verbal reports of the old-time men and women of the tribe were varied,—some were actually contradictory.

7 Generosity is said to be a fault of Indian people, but neither the Pilgrim Fathers nor Blue-Star Woman ever held it seriously against them.

7 The coffee habit was one of the signs of her progress in the white man's civilization

7 from the tepee into a log hut, another achievement.

7 learned to read the primer and to write her name. Little Blue-Star attended school

8 For untold ages the Indian race had not used family names.

8 custom of civilized peoples.

9 The day of the first ice was her birthday.

9 How futile had been all these winters to secure her a share in tribal lands.

9 bronze figure

10 her riddle. "The missionary preacher said he could not explain the white man's law to me. He who reads daily from the Holy Bible, which he tells me is God's book,

10 The white man's laws are strange."

12 footfall of two Indian men

13 short-cropped hair, faded civilian clothes, white man's shoes

13 "Pray, who are these would-be white men?" she inquired.

14 these near white men speak my native tongue and shake hands according to our custom."

17 we are educated in the white man's ways

19 She accepted the relationship assumed for the occasion.

22 a habit now to tell her long story of disappointments with all its petty details.

22 two nephews, with their white associates, were glad of a condition so profitable to them.

24 "Dear aunt, you failed to establish the facts of your identity,"

24 ever the same old words. It was the old song of the government official

24 we'll fix it all up for you

24 one thing you will have to do,—that is, to pay us half of your land and money

26 We have clever white lawyers working with us.

28 In bygone days, brave young men of the order of the White-Horse-Riders sought out the aged, the poor, the widows and orphans to aid them, but they did their good work without pay.

30 tricksters

32 on the Sioux Indian Reservation, the superintendent summoned together the leading Indian men of the tribe. He read a letter . . . HQ in Washington DC

33 shock to the tribesmen. Without their knowledge and consent their property was given to a strange woman.

34 Chief High Flier

34 The Indian's guardian [the U.S. government] had got into a way of usurping autocratic power in disposing of the wards' property.

35 he called his little granddaughter from her play, "You are my interpreter and scribe,"

36 our land is taken from us to give to another Indian.

36 Go to Washington and ask if our treaties tell him to give our property away without asking us. Tell him I thought we made good treaties on paper,

36 Washington is very rich. Washington now owns our country. If he wants to help this poor Indian woman, Blue-Star, let him give her some of his land and his money.

"X (his mark)."

37 addressed to a prominent American woman.

38 his son with whom he made his home.

39 ten-mile trip to the only post office for hundreds of miles around

39 the letter destined, in due season, to reach the heart of American people.

39 Memories of other days thronged the wayside, and for the lonely rider transformed all the country. Those days were gone when the Indian youths were taught to be truthful,—to be merciful to the poor. Those days were gone when moral cleanliness was a chief virtue; when public feasts were given in honor of the virtuous girls and young men of the tribe. Untold mischief is now possible through these broken ancient laws.

40 the papers were made by two young Indian men who have learned the white man's ways.

41 folly of turning my letter into the hands of bureaucrats!

41 An inner voice said in his ear, "And this one letter will share the same fate of the other letters."

42 He could not go there with his letter.

43 he cast the letter into the flames. The fire consumed it. He sent his message on the wings of fire and he believed she would get it.

44 a coming storm

45 several horsemen whipping their ponies and riding at great speed

45 Indian police.

46 Sitting Bull

47 The superintendent says you are one of the bad Indians, singing war songs and opposing the government all the time

49 found him guilty. Thus Chief High Flier was sent to jail.

53 a vision. Lo, his good friend, the American woman to whom he had sent his messages by fire, now stood there a legion! A vast multitude of women

53 huge stone image

53 that of a woman upon the brink of the Great Waters, facing eastward.

53 she turned around,

53 She was the Statue of Liberty!

53 formerly turned her back upon the American aborigine.

53 compassion. Her eyes swept across the outspread continent of America, the home of the red man.

54 Her light of liberty penetrated Indian reservations.

56 singing native songs of joy for the safe return to them of their absent one.

57 Blue-Star Woman's two nephews.