LITR 5535: American

Romanticism

Sample Student Midterm 2006

Andrew P. Coleman

The American

Romantic Spirit: Man Becoming a

Part of Nature

The history of America has been a

romantic quest. Columbus’

conquest of paradise, the Puritan experiment in a new Christian society,

Jefferson’s lofty ideal that “all men are created equal,” and the frontier

spirit that summons every man to seek out his own destiny, all exemplify the

romantic spirit that has inhabited and driven the American psyche.

The development of the American consciousness has paralleled the rise of

romanticism as a philosophical, artistic, and literary movement.

Romanticism celebrates nature, individualism, imagination, emotion,

passions, heroes, folk cultures, the exotic, the medieval age, transcendence,

the gothic, and the remote and mysterious.

Romanticism was a reaction against Enlightenment rationalism and

empiricism and against the neoclassical artistic values of the 18th

Century, which exalted order and harmony. At

the same time, Romanticism rejected the dogmatic religion of the 17th

Century in favor of a personal, nature-based faith.

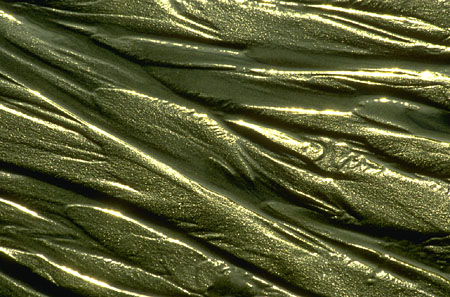

Romanticism possessed a heightened awareness of

and sensitivity to the beauties of nature; often Romantic writers described

nature in terms of the sublime.

Always present in American

romance is the stark beauty of the landscape.

Nature’s sublime beauty serves to inspire a sense of wonder and to test

the resolve of those who challenge its cold, cruel hand.

American romantic literature is enchanted by the magical beauty of the

untouched wilderness and darkened by its foreboding power.

Romance stories are typically a quest.

The assigned readings trace the “American quest” from Columbus’

discovery of the New World, through the spiritual and intellectual inward and

outward discoveries of Jonathan Edwards, and across Irving’s bridge between

man and nature, from the natural to supernatural.

The American romantic spirit finally, fully arrives in Cooper, the first

truly and completely romantic American writer.

Cooper was a man at home in and as a part of nature.

The American romantic epic is framed by nature, which stands as a

backdrop, always ready to serve as metaphor, vivid descriptor, or

personification.

Romanticism in Europe arose at

about the time of the American Revolution and it developed with the American

nation. As European settlers built

the nation out of seemingly infinite natural resources, romantic writers hewed

their imaginary poetry and prose out of the forests, mountains, flora, and fauna

of the land. According to Simone

Rieck, “Europe’s history, which includes hundreds of years of war and

disease, helps to create the natural setting for darkness and mystery, another

gothic theme. Without the capacious history, American authors were forced to

create a new gothic effect by using the lush untapped natural settings of their

young country.”

In the letters of Columbus, we

see the first romantic vision of the New World.

Columbus paints this dream in terms of the breathtaking beauty he

beholds. Columbus looks upon his

voyages as an otherworldly enterprise, but he describes the land in terms of its

rich natural beauty. In his

“Letter to Luis de Santangel Regarding the First Voyage” (26-27) Columbus

writes: “The island and all the

others are very fertile to a limitless degree, and this island is extremely so.

In it there are many harbors on the coast of the sea, beyond comparison

with others which I know in Christendom, and many rivers, good and large, which

is marvelous. Its lands are high,

and there are in it very many sierras and very lofty mountains, beyond

comparison with the island of Tenerife. All

are most beautiful, of a thousand shapes, and all are accessible and filled with

trees of a thousand kinds and tall, and they seem to touch the sky….

Española is a marvel” (26-27).

In his “Letter to Ferdinand and

Isabella Regarding the Fourth Voyage” (27-29), Columbus suggests “That lands

which here obey Your Highnesses are more extensive and richer than all other

Christian lands” (28).

In Columbus’ letters, we see

the American romantic spirit being born. Columbus

likens his arrival in the New World to visiting the Garden of Eden.

Imagining an earthy paradise and describing it in vivid natural terms has

always been characteristic of romanticism.

But Columbus does not become a part of that idyllic natural realm as the

true romantics do later. He seeks

to take possession of the land and to exploit it.

As Adam does in Genesis 2, Columbus exerts dominion over the land by

naming the islands and some of their creatures.

Eventually, Columbus, too, will be banished from paradise.

The English sought to colonize

and not to merely exploit, as did the Spanish.

Captain John Smith romanticized his time in America and through these

writings helped propel its colonization by describing the potential of the land.

In General History of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles,

Smith writes, “And now the winter approaching, the rivers became so covered

with swans, geese, ducks, and cranes that we daily feasted with good bread,

Virginia peas, pumpkins, and putchamins, fish, fowl, and divers sort of wild

beasts as fast as we could eat them, so that none of our tuftaffety humorists

desired to go for England” (47). Europeans

were learning to live more in harmony with the new land.

A countercurrent to the Age of

Enlightenment was the “Great Awakening” of the early and middle 18th

Century. By this time, the American

colonies were fully established and the Puritan movement was playing out.

It was at this moment in a New England pulpit that the pre-romantic

spirit became embodied in Jonathan Edwards who rose to challenge the skeptical

and materialistic spirit of the age. In

typical romantic fashion, Edwards looked to nature for clear descriptions of God

and man. Edwards had a keen eye for observation and a brilliant mind

for analysis. But Edwards did not

love science for science sake only. He

published scientific and philosophical works as a way to refute atheism and

materialism. For Edwards, nature

was a way of experiencing God.

Mary Brooks writes that

“Jonathan Edwards uses a combination of the sublimity of nature and the

sublimity of God in his Personal

Narrative. Edwards describes

his experience of finding God’s presence in nature’s ‘… majesty and

meekness joined together: it was sweet and gentle, and holy majesty; and also a

majestic meekness; an awful sweetness; high and great, and holy gentleness.’ God being all encompassing is often equated with nature

because human comprehension requires that even a vast entity without form be

visible. Edwards managed to find

his religious peace and center in nature’s plethora of vistas and phenomena.

Edwards uses the sublime to describe nature’s phenomena such as

thunderstorms as ‘… scarce anything, among all the works of nature, was so

sweet to me as thunder and lightening… and hear the majesty and awful voice of

God’s thunder….’ As often

happens with nature’s fury, it is so vast and incomprehensible that a

religious component is often added to explain seemingly random events as signs

of the sublime in God and nature. Nature

and God in Edwards’ narrative are inseparable.

Edwards finds his sublime religious meaning from being alone in the

vastness of nature and from encountering all the vast array of phenomena that

nature has to hold.”

God in nature, in gothic and

sublime forms, is also evident in “Sinners

in the Hands of an Angry God,” preached by Edwards at the height of the Great

Awakening. Edwards warns his

congregation: “The souls of the

wicked are in Scripture compared to the troubled sea, Isaiah 57.20.

For the present, God restrains their wickedness by His mighty power, as

He does the raging waves of the troubled sea…” (210).

Likewise, “There are black clouds of God’s wrath now hanging

directly over your heads, full of the dreadful storm, and big with thunder; and

were it not for the restraining hand of God, it would immediately burst forth

upon you. The sovereign pleasure of

God, for the present, stays His rough wind; otherwise it would come with fury,

and your destruction would come like a whirlwind, and you would be like the

chaff of the summer threshing floor” (213).

Washington Irving is a bridge

from the Age of Reason to the Romantic Era.

He possesses some classical attributes, such as satire, humor, and

detachment. But he also writes

distinctively romantic narratives, such as Rip

Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy

Hollow, in which the hero becomes detached from society and is relocated to

a gothic, natural environment. However,

the reader is never instructed on how to interpret these stories.

Are these romantic tales of the supernatural?

Or, should the enlightened reader realize that the hen-pecked Rip Van

Winkle wants to escape from a bad marriage, thus skipping town and returning

after his wife’s death and concocting his tale.

In Sleepy Hollow, does Brom

Bones disguise himself as the Headless Horseman to scare away his competition?

Whether one is a rationalist or a romantic may determine how one answers

these questions. Irving stands

astride both camps.

With the rise of a new nation a

new literature was needed to truly reflect the land and its people.

From the naked landscape James Fenimore Cooper carved out the first truly

romantic vision of America. Cooper’s

Leatherstocking Tales place

imagination above reason; they are truly romantic stories in which history is

only a frame, and nature is the backdrop. In

The Pioneers (Chapter III), Cooper

displays an early environmentalist sentiment—Natty Bumpo complains of the

wholesale slaughter of pigeons. This

is a developing facet of romanticism: the

sanctity of nature and man being a part of nature.

This represents a change from the early and pre-Romantics who cherished

nature, but looked upon nature as if they were separate from it.

Last

of the Mohicans is an example of “The Wilderness

Gothic,” in which the medieval haunted castle of traditional European gothic

romance is transformed into the foreboding power of the wilderness.

Such dark recesses are the sites of hidden sins.

The romantic hero, on a quest, arrives and stirs up the ghosts of past

disputes. Cora

and Alice are like heroines of old entering a haunted castle.

Magua personifies the spirits of lust and revenge, and the racial

elements serve as gothic symbols for light and dark, good and evil.

Yvonne Hopkins writes that “Of

the two sisters, Alice represents the old world, removed from nature, the

inhabitant of an artificial environment. In Cora, however, the mystery of her

heritage, her dark looks, and her determination mark her as a woman suited to

the challenges of the environment. While Alice projects the damsel in distress,

Cora projects the survivor, able and willing to adapt; and, therefore, eminently

worthy of taking her place in the natural setting of the frontier.”

The frontier allows characters to

commune with nature in its sublime beauty.

But nature also can be cruel and can allow ferocious violence, such

as the Indians’ massacre of the English at Fort William Henry.

Nature poses real danger. The

travelers struggle to make it through the wilderness.

However, because they have become a part of nature they are able to use

nature to their advantage. For

example, they use the fog as cover and hide their tracks by walking through the

stream (Chapter 14). Hawkeye lives

the idealized life of the wilderness. He

is at home in the Indian and white cultures, and he lives according to the

natural rhythms of the land. The

Last of the Mohicans idealizes nature over

against European civilization.

That

man can become part of nature is shown when Hawkeye successfully disguises

himself as a bear (Chapter 24) or when Chingachgook poses as a beaver (Chapter

27). In reality an Indian eye would

have caught on immediately. But in

Cooper, romanticized characters can merge into their natural surroundings.

Writes Hopkins, “The

significance of man’s oneness with nature is further emphasized in Uncas’s

connection to the mythological turtle, the giver of life.

In tracing his heritage to the turtle, Uncas establishes a noble lineage

and a direct link with the natural world.”

The

new spirit of man as part of nature is contrasted with the character, David

Gamut, a Calvinist psalmist. His

pitch-pipe, a symbol of civilization, is of little use in the wilderness.

Hawkeye and friends are able to thwart nature’s challenges, subtly

refuting the Calvinist notion of man being unable to alter his destiny, which

according to Calvinism is predetermined. This

new sense of freedom, based on the assumption that since man is part of nature

he has the power to determine its outcome, embodies the new free spirit of

America.

|

|

|

|