Sample Student Research Project 2012

Journal

LITR

4232 American Renaissance

Sample Student Research Project 2012

Journal

April Bucy

25 April 2012

Choose Your Own Renaissance:

The entire history of women's struggle for self-determination has been muffled

in silence over and over. . . . Each feminist work has tended to be received as

if it emerged from nowhere; as if each of us had lived, thought, and worked

without any historical past or contextual present.

—Adrienne Rich, "Foreword," Lies

This is not the traditional story, with a plot, a setting, and a complete list

of characters each with a differing problem,

this is more of a dialogue of the quest to uncover those female writers of the

American Renaissance that could be considered lesser known, however still of

equal importance to the movement as a whole. But first, one must work to define

the American Renaissance, altogether—a notion which may be a bit problematic as

you will see later in my own transcriptions. So, what do I mean when I talk

about the American Renaissance? Is it merely a particular time period or is it

considered a particular set of writers considered innovative in their individual

creativity and methods of literary exploration? For the purpose of our own

assessment, I chose to use the definitions outlined in the course syllabus by

Dr. Craig White, which states:

“Historically or culturally,

it's the literary and cultural period from about

1820 to the 1860s—or, the

generation before the American Civil War (1861-65), when the USA grew to its

present size and began to deal with some of the unsolved issues remaining from

the American Revolution.”

The term “renaissance” can also be read as a sort of “revival” providing the

foundation of which American Literature chose to stand and at the same time

marking its arrival to the rest of the world as a Literature force worthy of

comparison and criticism. This period is saturated in movements centered on

discovery, innovation and advancement, the quests for equality and rise of

literacy all of which are reflected in one way or another in its Literature.

Similar to later periods of Literature across the globe, the American

Renaissance is often correlated with specific authors considered masters of

their own craft such as Edgar Allan Poe and the gothic, Frederick Douglass and

the slave narrative, Henry David Thoreau and the transcendental movement,

Harriet Beecher Stowe and domestic sentimentality among other famous writers of

the American Renaissance. It is not my intention to imply that these individuals

were not important to the totality of the movement; however my tendency to

support the underdog led me on this literary journey to find those lesser known

female writers of the American Renaissance and hopefully, along the way

encounter books and authors to add to my ever growing summer reading list.

Whose

Renaissance?

Sharon M. Harris in the article, “Whose Renaissance? Women Writers in the Era of

the American Renaissance,” indicates that much of the information about the

American Renaissance is centered around “a limited group of extraordinary

writers—the romantics and transcendentalists—and such key issues as

self-reliance, the relation of humans to their environment, and religious

liberalism” (59-60). However, as the old Bob Dylan song suggests, “times are a

changing,” and as a result of these changes “newer theoretical interests, such

as feminist, post colonial, and cultural studies, opened the field to include

texts that address the early abolition movement, constructions of gender and

sexuality, empire building and the effects of immigration” (Harris 60).

It is not surprising that in the center of all these changes and

challenges to culture the notion of “diversity of opinion” became paramount, as

did the need to redefine the boundaries of the American Renaissance.

Historically, Harris suggests that “in 1829 only a handful of women were

publishing books,” and that a select few such as Catharine Beecher, Sarah

Josepha Hale, Lydia Maria Child, “enjoyed national recognition as authors.” What

became important to me, as the article progressed was not only

who these women were, but

what they chose to write as a

representation of themselves and other women of the time period. As it turns

out, “poetry and nonfiction dominated women’s publications of the 1820’s” and

while these remained popular choices for the remainder of the Renaissance, from

1830 to 1855 there were major changes in how women represented themselves as

icons among the literary world. Harris indicates that there was “an increased

interest in history writing; the emergence of substantial attention to

children’s literature and to African American and Jewish American women’s

writings; a new interest in philosophical and scientific writings and an

extraordinary production of novels, dramas, and autobiographies” (61). According

to the author, the increase in the desire to write children’s literature spurred

from the “interest in history writing and with increasing opportunities for

education” both of which are reflected in Eliza Farrar’s

Story of the Life of Lafayette, as Told

by a Father to His Children (1831).

Sarah Josepha Hale was also an author who was interested in the expansion

of education and history and is credited with producing novels “supporting U.S.

colonization projects, including removal of free African Americans to

“liberation” in Africa” in the novels

Liberia and Mr. Peyton’s Experiments

of 1853 (Harris 63). The impact of both children’s literature and historical

representations in literature lend themselves to several questions all of which

are articulated by Harris: Are there correlations between these genres, and to

what extent is children’s literature implicated in nationalist agendas? Do

juvenile texts tend to advance our idea of the American Renaissance as a period

of individualism as well as a period of concern for inclusion? And lastly, to

what extent do they orient themselves toward reform or, at the other end of the

spectrum, lend themselves as tools for normalizing conduct? (Harris 63).

The ways in which women are represented as a symbol of the domestic were

numerous; however this notion of domestic sentimentality was challenged by some

women writers that “began to present the arena of home as an integral part of

the marketplace and capitalist consumerism” (Harris 64). Hannah Farnham Sawyer

Lee’s novel, Three Experiments of Living:

Living Within the Means, Living Up to the Means, Living beyond the Means

according to Harris uses speculation as a lure of a young couple, “into the

abyss of extended debt and financial ruin,” a concept that although especially

familiar to 2012 seems a bit out of place for nation its early stages.

Harris questions the malleability of domesticity in regard to the

emerging New Women’s movement by stating, “How did the debates of this period

shape the post Civil-War development of the New Women’s movement and was there

in fact a New Women movement pre-Civil War as well—one that helped to defeat the

proscriptive values of True Womanhood and separate spheres of ideology?” (64).

One of the ways women challenged “limitations on domesticity” was through travel

writing, specifically travel journals. Harris suggests that “women used travel

to advance their opportunities, to move beyond the domestic, but equally so to

participate, sometimes wittingly and sometimes not, both within and outside

national boundaries” (65). Authors such as Anne Royall, Sarah Josepha Hale,

Fanny Hall and Caroline Howard Gilman were thought to be “reviving the genre” by

reconstructing “their roles in society” but using the feminine role of “observer

to advance or refute imperialist agendas”, giving themselves agency and making

otherwise silent women’s voices heard (65).

Children’s Literature and travel journals were not the only areas that women

writers gained notoriety, drama, and poetry provided an outlet for women as

well. Scholarly articles about philosophy and science, history and geography did

gain a large amount of interest and although they accrued little recognition as

being produced by women, authors such as Mary Griffith who published,

Our Neighborhood; Letters on Horticulture

and Natural Phenomena (1831) continued to challenge conventional notions in

public culture (Harris 67). The bigger question then becomes, how impactful can

texts written by women “in an era when science and philosophy were highly

gendered and racialized” be in changing existing constructions of gender and

race? This seems to be a question that merits further investigation and at the

same time still bears limits today. The Harris article provided the foundation

needed to map out the course of this journal and bestowed upon me a variety of

lesser known female authors and movements of which I took great interest.

Children’s

Literature: Buried Treasures

Harris referenced a large number of women writers with whom I was completely

unfamiliar, leading me to conduct my own literary treasure hunt of children’s

texts. I have listed the examples below and although I did not read any of them

in their entirety, there was an overwhelming theme in each work of moral

fortitude and at the same time each provided a sense of nationalism and

religious integrity. These themes directly correspond with concepts of the

American Renaissance referenced in class discussions which I found extremely

interesting especially since the works were done by writers that have little

significance in large anthologies of Literature.

Eliza Farrar’s Story of the Life of

http://archive.org/stream/storylifelafaye00cogoog#page/n12/mode/2up

This book chronicles the acquisition of an empire in the name of a monarch, a

concept reminiscent of

Sarah Sedgwick’s Young Emigrants

(1830)

http://archive.org/stream/theyoungemigrant11585gut/11585.txt

The life of the Gale family, once respectable Londoners under the safety of the

Divine Providence sell their belongings and vow to as start a new life in

Cincinnati on two eighty-acre lots.

Dorothea Dix’s American Moral Tales for

Young Persons (1832)

http://archive.org/stream/americanmoraltal00dixd#page/n3/mode/2up

As the title suggests, this book serves as a guide to right and wrong for

children. What I found most interesting in my research was not about this book,

but rather that

Dix’s best

known children’s book, Conversations on Common Things (1824) was designed

to help parents answer everyday questions such as: "Why do we call this day

Monday? Why do we call this month January? What is tin? Does cinnamon grow on

trees?"

Frances Manwaring Caulkin’s Children of

the Bible: As Examples and as Warnings (1842)

http://archive.org/stream/childrenofbiblea00caul#page/n3/mode/2up

Each chapter outlines a child referenced in the bible as well as a moral message

associated with that individual, such as Ishmael as a representation of the

influence of prayer and Moses as an example of resisting temptation. As a side

note, the pictures in this book are absolutely beautiful and I found it

interesting that there was no credit given to an illustrator which could imply

that Ms. Caulkin was not only a writer but also an equally talented illustrator.

Eliza Leslie’s American Girl’s Book

(1831)

http://archive.org/stream/americangirlsbo00leslgoog#page/n10/mode/2up

This is a collection of “hints for happy hours” and contains “amusements for all

ages.” The introduction of the book is written in the form of a dialogue between

a mother and her children and serves as an argument for why “sports and

pastimes” are important in the lives of children. The book reads like an

encyclopedia of appropriate activities.

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody’s Holiness (1836)

http://archive.org/stream/holinessorlegen00peabgoog#page/n1/mode/2up

This is an adaptation of Spenser’s The Faerie Queen and is credited as being

written by “a mother,” otherwise known as

Sarah

Josepha Hale

While searching for information about women writers of children’s literature of

the American Renaissance, to supplement those articulated in the Harris article,

I stumbled upon Sarah Josepha Hale who

is credited with being extremely influential in the political consciousness of

women and integral in developments of reading, learning and writing during the

American Renaissance.

Sarah Josepha Hale was born on October 24th, 1788 in

Sarah was widowed in 1822 with five children to support, four under the age of

seven. In an effort to support her struggling family, she took a job in a

millinery shop, although she longed to support her family with her writing. In

late 1822, she published her first book of poems, The Genius of Oblivion,

with David Hale's Freemason lodge paying for the publication but it wasn’t until

the publication of her first novel in 1827,

Northwood, that her career as a writer was firmly established (

I became most interested in Hale’s ties to Godey’s Lady’s Book which “was

intended to entertain, inform and educate the women of America” and of which she

served as editor from 1837-1877 (Niles). Godey’s Lady’s Book contained

“extensive fashion descriptions and plates, biographical sketches, articles

about mineralogy, handcrafts, female costume, dance, equestrienne procedures,

health and hygiene, recipes and home remedies” (“Godey’s”). Every issue also

contained “two pages of sheet music, written essentially for the pianoforte” and

as its popularity grew, “the periodical matured into an important literary

magazine containing extensive book reviews and works by Harriet Beecher Stowe,

Edgar Allen Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and many other

celebrated 19th century authors who regularly furnished the magazine with

essays, poetry and short stories” (“Godey’s”).

During Hale's editorship, “Godey's published at least three special issues that

included only female writers” while at the same time providing “a substantial

literary diet for readers as opposed to the ephemeral poetry and fiction that

clogged most women's magazines at the time” (

According to historians, “her steadfast devotion of purpose and her unwavering

editorial principles regarding social inequalities and the education of American

women, made her one of the most important editors of her time” evident by the

increased popularity of the periodical which “reached a pre-Civil War

circulation of 150,000” (“Godey’s).

Eventually Godey’s proved to be too conservative for certain members of the New

Women’s movement so women were forced to find less formal outlets of agency;

however,

Godey’s Lady’s Book is still

considered to be “among the most important resources of 19th century American

life and culture” (Godey’s).

Circe as the Innovator of Domesticity

Continuing my search for women and their role in the implementation of the

American Renaissance, I came across a book whose introduction both startled and

intrigued me by implying the notions of women and domesticity began with Homer’s

The Odyssey. Ann Romines, in the

introduction of her novel, Home Plot:

Women, Writing and Domestic Ritual, categorizes Circe as the

archetypal beginning of the “assertion of will through domestic ritual” making

her both “powerful and powerless, both qualities are rooted in her gender” (4).

The “palpable tension between the wanderer (Odysseus) and the housebound witch

(Circe) is in many ways the quintessential story, toward which much of the

previous hundred years’ worth of fiction by American women has been pointing”

(5). I found several pieces of the introduction problematic but I must admit its

overall purpose was achieved, specifically its ability to reel me in as a reader

and thus making me interested in the rest of the book. The introduction

continued to reference Harriet Beecher Stowe as an advocate for “faculty,” a

term used synonymously with domesticity stating that “faculty is a high art”

(Romines 6). This was particularly interesting especially because although Stowe

is considered a writer of domestic sentimentality, I never would coin her with

the term advocate. This may be due primarily my own biases grounded in

foundations of gender studies, or perhaps it is based on the rose-colored

glasses I chose to wear. Regardless, I thought it was important to document the

discovery of this book due to its unconventional and overly problematic retorts

as well as its ability to keep me interested in what other critics had to offer.

Interesting Web Site

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/ihas/icon/transcend.html

I found this

particular website significant due to its breakdown of writers of both genders

and their contributions to the American Renaissance. The site also provides a

great deal of information on the transcendental movement that you may find of

interest the next time you teach this course.

Final Thoughts

Similar to most “choose your own adventures” the beginning of the project did

not directly affect the ending. Each source offered additional sources but the

cyclical nature of the topic eventually offered a method of piecing it all

together. I originally sought to find a

massive list of influential female writers (of a lesser popularity but of equal

importance) and along the way discovered Children’s Literature of the American

Renaissance and Godey’s Lady’s Book. Along the emblematic romanticized journey I

discovered Dorothea Dix, who intrigued me as an advocate for the proper

treatment of the mentally ill and also as an author of children’s literature and

Sarah Jospeha Hale who spent 40 years as editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book. I found

myself distracted by travel journals and articles on horticulture as well as the

pivotal role of women in genres that were originally characterized as primarily

male. I worked to redefine the female role in the American Renaissance and

discovered that there were a larger number of lesser known influential women

than I ever imagined. Women of the American Renaissance accomplished a great

feat; it is because of them that even today we cannot wholly grasp their

importance and position as both women and artists in

Works Cited

“Godey’s Lady’s Book." Accessible Archives Inc. 2012. Web. 25 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.accessible-archives.com/collections/godeys-ladys-book/>.

Niles, Lisa. "Sarah Josepha Hale." Women Writers: A Zine. University of

Central

Romines, Ann. Home Plot: Women, Writing and Domestic Ritual.

Sharon M. Harris. "Whose Renaissance? : Women Writers in the Era of the American

Renaissance." ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance 49.1 (2003):

59-80. Project MUSE. Web. 23 Apr. 2012. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>.

White, Dr. Craig. "Terms & Themes.". University of

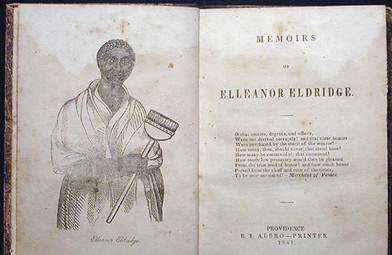

Images Extracted from:

Elleanor

Eldridge:

http://www.classicbooksandephemera.com/shop/classic/000730.html

Godey’s

Lady’s Book:

Sarah

Josepha Hale: