Sample Student Research Project, spring 2006

LITR

4232: American Renaissance

Sample Student Research Project, spring 2006

Kate Barrack

May 4, 2006

With Violence and Madness We Walk Unknown

When in the Creation of literary styles, it becomes necessary for one author to dissolve the stylistic bands which have connected him with another, and to assume among the potentials of a writer, the separate and non-equivalent station to which the Rules of Literature entitle them, a decent consideration to the methods of these authors requires that we should discuss the causes which impel them into separation[1]. Through the exploration of a lifetime of literature, a few authors manage to poke an impression on our minds, regardless of our final personal opinion about their works. While the reasons for this phenomenon may vary quite a bit between these unique characters, an examination as to the nature of their personage, their stories and their language may, in fact, reveal some similarities. Focusing on the periods of the British Victorian movement and the American Renaissance, or Gothic, movement, I would like to explore the surprising popularity of Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe. I say surprising because these two authors, while well known, don’t seem to be lauded by the critics of the academic community. Instead, their works are often viewed as curious oddities within the scope of popular literature. What exactly vaults these two authors past the authority of academia and into the hearts of the average reader? As I will show, this fame is the product of eccentric personalities, an unexpected use of language, a departure from otherwise sensible notions of life, and underrated literary talent.

Oddities of the Public Spectrum

Poe, although mostly known for his horror stories, was actually a prolific critic of the literary world. Beginning in 1835 at the age of twenty-six, less than a decade after his first poems were published, Poe is hired as an editor for the Southern Literary Messenger. Almost immediately, his “uncompromising reviews attract the attention of literati throughout the nation” (Hayes xvi). His unique perspective of the aesthetic sense seemed to be well ahead of its time. He embraced the notion that art should be created for art’s sake, but should still have a purpose (Hayes 42). Perhaps not surprisingly, Poe rejected the organic metaphors of the Romantics (Hayes 43). A quick glance at any of Poe’s poetry or short stories, reveal a noticeable lack of the interplay of nature as an end in itself. Instead, Poe limits his settings to domiciles constructed and inhabited by man. Consider the settings of “Legeia”: a house and later a single bedroom. These settings become characters in their own right, influencing the protagonists and driving the theme of Poe’s stories. By rejecting the Romantics’ ideas, he instead preferred to view art as a clever illusion, much like a mechanical problem (Hayes 43).

Additionally, his theory of aesthetics lauds “suggestiveness and indefinitiveness over coherence of subject matter” (Hayes 44). Again, consider the ending of “Legeia.” Can the reader be absolutely sure that the protagonist’s beloved has come back from the dead, or that her spirit merely possessed a dead body, or that the protagonist has simply imagined the entire ordeal? Commenting on Poe’s sensibilities, T. S. Eliot once remarked that Poe’s ideas “seem to be entertained rather than believed” (Hayes 46). Whereas the Romantics deeply desired the reader to believe and share their aesthetic considerations, it seems that Poe has left a moralistic opinion out of his work. All of these ideas are far removed from the mainstream movement of the literary conventions of his day, yet when we look back on his work, we describe him as a popular author.

Well known to riddle aficionados and cryptographers, Lewis Carroll operated well beyond what might be considered, the boundaries of his profession. By trade, Carroll was a trained mathematician. In 1954, Carroll earned his Bachelors in mathematics, followed quickly by a Masters in 1857. It wasn’t until Carroll was thirty-three that his most famous work, Alice in Wonderland, was published. Having befriended the Tennyson family, his work has been criticized as children’s stories that only the children of writers would enjoy (Watson 546). Judging by his legacy, however, this seems to be an unfair criticism. As a fiction writer, Carroll did not have a particularly robust career. Through the Looking Glass was published in 1871 and after that point, mostly he focused on mathematical texts (Cohen xvi).

At the young age of forty, Poe died, possibly due to alcohol poisoning. Carroll managed to outlive the American author by a robust twenty-six years. Both poets, however, were published posthumously. Additionally, the particular texts that were published harken quite well back to the life and theories of these writers. For Poe it was “The Bells,” and “Annabel Lee;” both poems deal with a consideration of death and the afterlife (Hayes xix). For Carroll, “Three Sunsets and Other Poems” contain gentle, sentimental views of love and life, an aspect of his private self that was well-known to friends, but not to fans of Alice (Cohen xvi).

| from “Annabel

Lee”

… But our love

it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we— And neither

the angels in heaven above,

Nor the demons down under the sea, Can ever

dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee: For the moon

never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; And the

stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee: And so, all

the night-tide, I lie down by the side Of my

darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In the sepulcher there by the sea—

In her tomb by the sounding sea. [published, 1850] (Poe 2546) |

from “Solitude”

… To live in

joys that once have been,

To put the cold world out of sight, And deck

life’s drear and barren scene

With hues of rainbow-light. For what to

man the gift of breath,

If sorrow be his lot below; If all the

day that ends in death

Be dark with clouds of woe? … I’d give

all wealth that years have piled,

The slow result of Life’s decay, To be once

more a little child

For one bright summer-day. [published 1898] (Carroll 902) |

A Story About Nothing At All

Both authors managed to create poems that have remained extraordinarily famous. Poe’s “The Raven,” explores the slow psychological torment of a lonely man, while Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” relives the adventure of a young boy on a quest to slay an imaginary creature. While both poems can be read as curious and perhaps trite stories, the language each author uses indicates a deeper consideration than a mere plot.

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing farther then he uttered—not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered ‘Other friends have flown before—

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before.’

Then the bird said ‘Nevermore.” (Poe 2540)

Considering the repetition of the bird’s speech in “The Raven,” most readers are content to view the creature as a mocking tormenter. However, it is also possible to view the protagonist’s request for information with the bird’s response, as a refusal for needed information. Poe was concerned with the relationship between “subjective and scientific knowledge and the possibility of knowledge and certainty” (Freedman 147). In this light, the human represents everyman who questions our perception of reality while the bird represents a blockade between necessary information. Perhaps even more frustrating, the bird can also represent the idea that more knowledge exists, but that we are being explicitly denied. “Nevermore” is both a straightforward reply and a refusal to respond to a plea for an answer (Freedman 148). Read from this perspective, it could seem that “The Raven” is a story about “Nothing.”

Definitely more playful, but still quite dark, “Jabberwocky” represents a triumph of Nonsense literature. Based upon the known rules of grammar, Carroll has successfully used twenty-five invented words without turning the poem into an incomprehensible mess.

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And, as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came! (134)

The pleasure of the text is not gained from the individual experiences of having to read the poem two ways (once for each possible meaning of the strange words), but by way of both readings having been packed together (Goldfarb 87). Like Poe’s raven, where a troubling feeling is produced by the lack of meaning from “nevermore”, Carroll creates an anxiety of action that is heightened by his use of nonsensical words (Goldfarb 88). While the reader can associate some subjective meaning to the invented words, in reality, they mean nothing at all, regardless of their grammatical placement.

Curious Aesthetics

While it may not be unusual for an author to draw the reader into the action of a scene, the methods by which Poe and Carroll create this invitation are perhaps the most telling of their aesthetic senses. Poe is widely, if not universally, thought of as a Gothic artist. His tales of the macabre and surreal immediately make striking impressions upon most readers. Perhaps this is simply because his works are studied against other compositions that do not focus specifically on horror alone. It would probably be incorrect to suggest that “most literature” deals with realistic, or at the very least, plausible events and that because of this, Poe’s horror works stick out merely because they are horror. However, even if taken in comparison with other Gothic horror stories, Poe still makes a unique impression. So if the reason Poe’s impression is so strong is not simply because of the genre, then what is it?

If the Gothic aesthetic is to present a high contrast of darks and lights [“Once upon a midnight dreary [...] For the rare and radiant maiden” (“The Raven” 1-11)], and if horror is to explore death (or mortality) in a manner that is outside of the realm of acceptable behaviors of society [“And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side / Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride, / In the sepulcher there by the sea— / In her tomb by the sounding sea. (“Annabel Lee” 38-41)], and if the sublime is an unintentional moment of otherworldliness or spirituality that is somehow profound [“Mountains toppling evermore / Into seas without a shore; / Seas that restlessly aspire, / Surging, unto skies of fire;” (“Dream-Land” 13-16)], then Poe’s unique contribution to literary aesthetics is primarily psychological. In several poems and stories, Poe has left his protagonist unnamed. One result of this is for many readers to associate Poe as the character in his stories.

The other result is a piece of literature that is invitational to the reader. By looking through the characters who lack an extensive back-story, the reader is given an almost second-person perspective in the story. Compound this with the often violent subject matter and the result is a force of psychological suction. Poe’s violence is invitational and genuinely frightening yet it acts like a catharsis (Hayes 68). Additionally, Poe often relies on a psychological projection of fear and isolation especially within relations involving dominance or victimization (Folks 2). Perhaps the strongest draw for readers is the successful incorporation of sadomasochistic elements that lack any overt sexual element (Pritchard 144). All of these elements are superbly incorporated in The Tell-Tale Heart.

He shrieked once—once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done […] If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. (2494)

Key to Poe’s sadomasochistic horror was the involvement of the reader. As shown in the passage above, this was accomplished by presenting the protagonist as a sane and intelligent man. That is, there appears to be a suggestion that cruelty of such refinement and appreciation can only be exhibited by a civilized man; i.e. his readers (Pritchard 145).

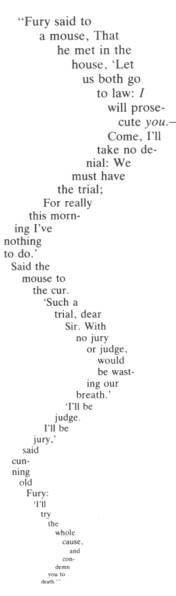

As Poe allows the reader to “enjoy” a murder, Carroll invites the reader to find himself in a world of madness. Alice in Wonderland, although about a little girl’s adventure, is hardly lauding the prim and proper attitude her Victorian teachers represent. The reader may recognize Alice’s sensibilities, but will be more entertained by the maniacal characters she meets. While Alice is reasonable, the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, the White Rabbit, the Caterpillar, the Queen, and all the rest are all outlandish, possibly insane, characters (Watson 547). Much like the irrational act of taking pleasure in murder, Carroll’s story seems to be an adventure against reason and sanity. For the adult reader, the stories may come across as “rancidly cynical” (Watson 546). Indeed, Carroll’s favorite “inside-out device” is to make wild social commentary from a nursery rhyme (Watson 543). No doubt, Alice’s encounter with the Mouse’s tale (see appendix) is a direct jab at some political and judicial attitudes of Carroll’s day. While Alice will have little to no understanding of the Mouse’s tale, possibly brushing it off as another encounter with the nonsense of Wonderland, the adult reader will begin to see a slew of such commentaries from each of the characters. Setting social criticism inside a world of chaos and madness is extremely dismissive (Watson 546). Thus, the reader is able to make fun of certain ideas without having to deal with them directly. So like Poe, Carroll incorporates a very subversive psychological approach in his stories.

Understated Style

It would be unfair to say that both Poe and Carroll are “unrecognized” authors, even in the academic world. Both are given due time in courses from grade school to college. However, if compared to other great authors from the Western Canon, many scholars might be tempted to suggest that the impact of these two authors has been primarily popular. Additionally, the quality of prose is often called into question as well. “The issue of Poe’s ‘style’ has long been a contentious one—and it remains so. Those who have found fault with his prose include Henry James, Yvor Winters, T.S. Eliot, Margaret Fuller, Mark Twain […] Some of these have argued that Poe was a bad stylist and that his narrators all sound the same” (Zimmerman 637). Likewise, one of the most widely know children’s stories, Alice in Wonderland, has been criticized for being too obscure for the supposed audience. “’Any real child,’ remarked a nameless critic in The Athenaeum (December 16, 1865), ‘might be more puzzled than enchanted by this stiff, over-wrought story’” (Watson 544).

Given the continued popularity of both authors, something is amiss. Brett Zimmerman, curious about the overwhelming criticism of Poe’s style began to catalogue the various devices used in Poe’s stories and poetry. Contrary to the academic/professional opinions, Zimmerman found twenty-three types of devices of balance, with a fondness for parallel structures. Additionally, he found two dozen descriptive devices and three dozen types of emotional appeal (638). Coincidentally like Carroll, Poe’s uses of “ungrammatical, illogical or unusual uses of language” seem primarily reserved for verbal comedy (Zimmerman 638). Carroll’s work is similarly under-recognized for stylistic attributes. Although he is well known for his contribution to Nonsense, less discussed is his incorporation of classical themes, such as to Dante’s Inferno (Goldfarb 87). Also like Poe, Carroll has a fondness for parallelism, as is seen in the first and last stanza of “Jabberwocky.” What appears to be redundancy is actually “homecoming: recognition” (Goldfarb 88).

Both authors also incorporated some form of obsessive ritual within their stories. In The Fall of the House of Usher, the Usher family is obsessed with fulfilling certain requirements, be they philanthropic, academic or artistic (Folks 8). In Wonderland, while the events are topsy-turvy, almost all of the characters have some kind of ritual as well. The White Rabbit has little to say, except his reminders that he is not on schedule.

There may also be another component to reading the works of Poe and Carroll. While choice of words will indicate the setting or tone of a story, Poe didn’t stop there. In his poem “The Bells” he manages to create a “jovial tone with more than just sounds. The choice of words creates a physical change in the face, similar to smiling (Graham 10). For Carroll, sound plays a crucial role in the success of his poetry. Once again regarding “Jabberwocky,” a twelve year old, Jonathan Lillian pointed out that the “language … almost makes sense when you read it. The words sound and are spelt like normal words in English, but the poem is imaginary in its physical language” (Flescher 133). That is, “meaning, however undefined, is nevertheless suggested” because of the sounds used (Flescher 133).

Summary

The point of this exploration of similarities between Edgar Allan Poe and Lewis Carroll has not been to suggest that these authors are intrinsically similar, either via their texts or lives. Rather, this comparison has revealed similar impacts upon the reader. Both authors had unusual and controversial lives, but their impact upon the world is primarily due to their writings. Filling the literary landscape with madness, violence, nonsense, and obsession, both authors have created worlds that function to release the reader from an otherwise rational, sane life. Within the world of fiction, these two authors have completely removed their characters from our reality yet, they have left enough of a breadcrumb trail for the readers to follow along. Perhaps it is because of these extreme fixations away from normalcy why readers gravitate to these works. Both Poe’s and Carroll’s use of language is also particular and recognizable. Whether it is Poe’s dark and light world, highlighted by blood, death and love, or Carroll’s upside-down landscape of literal fallacies and Tumtum trees, both writers have created worlds to fascinate our senses, without an apology for never letting up for even a moment.

Future consideration of this topic might ask which writers of today have used this saturated method and if they have been as successful, or if there is another aspect to Poe and Carroll, possibly concerning the time during which they lived, which also contributed to their ongoing fame. On a purely psychological level, one might wish to further consider the impact of the authors’ private lives upon their writing. Linguistically, it would also be interesting to study the impact Poe and Carroll have had upon the English language, as I suspect it to be larger than a few words. While a great deal of consideration has been given to the works of Poe, I was disappointed by the lack of a large selection of academic studies for Carroll. Most information was either biographical or dealt primarily with Nonsense, specifically in Jabberwocky.

In the end, however, I am fairly satisfied with the number of comparisons I was able to draw from the available literature. Both authors will continue to fascinate my senses as well, and I will gladly continue to accept their invitations into the madness.

Appendix

“The Mouse’s Tale” (Carroll 35)

The final two “bends” read as follows:

“said cunning old Fury: ‘I’ll try the whole cause,

and condemn you to death.’”

Works Cited

Carroll, Lewis. The Complete Illustrated Works of Lewis Carroll. London: Chancellor Press, 1982.

Cohen, Morton N. ed. The Selected Letters of Lewis Carroll. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Flescher, Jacqueline. “The Language of Nonsense in Alice.” Yale French Studies 43 (1969): 128-144.

Folks, Jeffery J. “Edgar Allan Poe and Elias Canetti: Illuminating the Sources of Terror.” Southern Literary Journal 37.2 (2005): 1-16.

Freedman, William. “Poe’s THE RAVEN.” Explicator 57.3 (1999): 146-8.

Goldfarb, Nancy. “Carroll’s Jabberwocky.” Explicator 57.2 (1999): 86-8.

Graham, Kevin. “Poe’s THE BELLS.” Explicator 62.1 (2003): 9-11.

Hayes, Kevin J. ed. The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Poe, Edgar Allan. (Collected Works) The Heath Anthology

of American Literature: Volume B, Early Nineteenth Century: 1800-1865. Ed.

Paul Lauter. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006.

2459-2546.

Pritchard, Hollie. “Poe’s THE TELL-TALE HEART.” Explicator

61.3 (2003): 144-6.

Watson, George. “Tory Alice.” American Scholar 55.4 (1986): 543-52.

Zimmerman, Brett. “A Catalogue of Selected Rhetorical Devices Used in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe.” Style 33.4 (1999): 637-57.