Sample Student Research Project 2013

Journal

LITR

4232 American Renaissance

Sample Student Research Project 2013

Journal

Mickey Thames

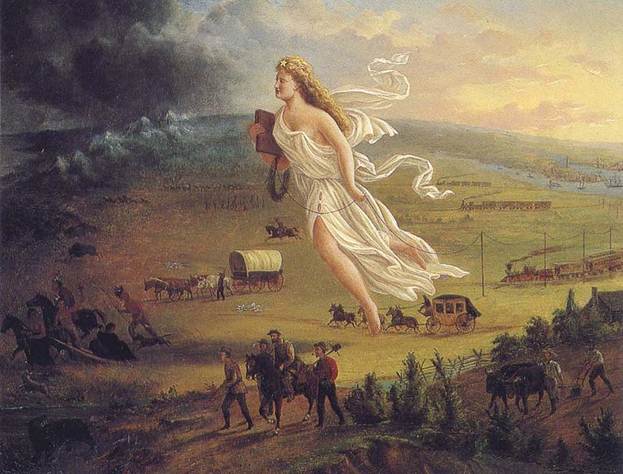

American Progress- John Gast 1872

Why the West Was Won--Manifest Destiny

Introduction

American exceptionalism; that idea that somehow, we Americans

are set apart to do great deeds and lead the world into a better society. I’ve

often wondered where this idea sprang up in our history, and how it managed to

so ingrain itself into our culture. How did it manage to influence multiple

generations in the realms of foreign policy, economics, and literature?

What I stumbled upon was the idea of Manifest Destiny. The idea that

America, as a nation, much stretch from “sea to shining sea” appears all over

literature from the time of the American Renaissance, and I intend to find out

where this idea came about (Bates).

In this journal, I am going to discover the first usage of the term Manifest

Destiny, its roots in the American expansion westward, and find out why people

believed in it. I am eager to find the political machinations that ensued, or

were behind its rise to popularity, and wonder how it transformed into the idea

of American Exceptionalism. I will give general history and background

information about the movement, thanks to a few prodigious scholars.

I also plan to discover the origins of the term, break down the idea into

its most basic tenets, and analyze the literature of Ralph Waldo Emerson and

Abraham Lincoln to discover embedded examples of the idea. I also plan to review

the University of Groningren’s website on Manifest Destiny, to see a foreign

perspective of the expansion. And finally, I want to understand how the idea of

a Manifest Destiny is Romantic.

History

Manifest Destiny is the idea that America was meant to expand

from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, encompassing all the territories

between. Historian Frederick Merck defines it as “expansion, prearranged by

heaven, over an area” that was not yet part of the United States (p 24). He goes

on to say that this policy was originally one of peaceful expansion, to allow

peoples to ask for admission to the American system of their own volition (2).

And the first feat of expansion, the Louisiana Purchase, was just that. A

peaceful acquisition of territory from France in 1803, then-President Thomas

Jefferson doubled the size of the nation, and with it began the great move

westward. This new land introduced for Americans their first frontier since the

Revolutionary War, with writers such as Emerson and Whitman unwittingly

encouraging expansion with their Romantic essays such as Nature.

In 1818, Andrew Jackson on orders from President Monroe, led forces into

Spanish-owned Florida, and essentially took it from Spain, marking the second

expansion of the United States in twenty years (Lubragge). Because Florida was

part of the North American continent, people argued, it should be a part of

America (Lubragge). This idea, as historian Robert J. Miller, in his book

Native America: Discovered and Conquered, came “easi[ly] and comfortab[ly]

to Americans…[their] virtue, mission, and divine ordination mandated the

expansion of America’s borders” (120). This aggressive expansion continued with

the Mexican American War. President Polk, desiring to acquire more territory,

first annexed the Republic of Texas, then proceeded to go to war with Mexico

over its former colony and over half the lands that went with it (White). This

particular expansion came at the heels of the annexation of Texas, which

Americans took as another sign of people wanting to join the Union, and that

given time, the territories of California and Colorado would follow suit. They

were simply taking the initiative. And with its victory, America had secured the

vision of expanding from one ocean to the other.

First Use

The first use of the term Manifest

Destiny came in an essay by John L O’Sullivan, entitled Annexation.

Published in 1845 in his self-edited Democratic Review, O’Sullivan argues

for the annexation of Texas, citing the “greatness [of the people] and... the

fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by

Providence.” This was not the first allusion to a divine mission by O’Sullivan,

as he would use the phrase again, this time to much more attention, when he

published in the New York Morning News,

"...To state the truth at once in its

neglected simplicity, we are free to say that were the respective cases and

arguments of the two parties, as to all these points of history and law,

reversed - had England all ours, and we nothing but hers - our claim to Oregon

would still be best and strongest. And that claim is by the right of our

manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which

Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty

and federated self-government entrusted to us."

John L.O’Sullivan, “Manifest Destiny”

This editorial caught on with several political

groups, including the Democrats, who used it as a campaign slogan in the years

after. O’Sullivan would go on to influence a faction of the Democratic Party

called Young America.

Themes and Ideas of Manifest Destiny

The idea of Manifest Destiny was not solely the realm of

expansionist politicians. It was a group of beliefs that pervaded the culture of

America during the early to mid 19th century, and can be identified and applied

to a multitude of literary forms of the day. In his book, Native America,

Discovered and Conquered, Robert J. Miller puts for the following themes of

American Manifest Destiny:

“ 1.The Special Virtues of the American people and their

institutions;

2. America’s mission to redeem and remake the world in the

image of America; and

3. A divine destiny under God’s direction to accomplish

this wonderful task.” (120)

While none of these are openly expansionist, they can be

interpreted to allow for it. If the virtues of American peoples are special,

then they are superior to whatever indigenous population already inhabits an

area, and it is to the inferior people’s benefit if Americans colonize their

area. This line of reasoning feeds right into the second theme of a mission. The

idea of a mission is nothing new; it has existed in American Romanticism and

puts these ideas firmly in the realm of Romanticism. The third and final theme,

that of destiny, gives the appearance of operating under a higher power. This

idea is also from Romanticism, as a “higher law” is often a motivation to

accomplish something. These three themes, all being notions of Romanticism, also

fall under the idea of Transcendence. Following the direction of God, bringing

others ‘into the light’ of republican democracy, and instilling in others the

same higher characteristics of the American people all are aspects of

Transcendence.

Literature of Manifest Destiny: Abraham Lincoln

When looking for examples of literature that embodied the

tenets of Manifest Destiny, I decided to start at the top. Abraham Lincoln’s

writings are full of the virtue and mission described by the Manifest Destiny.

In his The House Divided Speech, he characterizes the Union as” the frame

of a house or a mill , all the tenons and mortises exactly fitting, and all the

lengths and proportions of the different pieces exactly adapted to their

respective places;” This description of the Union as a building, brought forth

with a specific purpose, preordained with “a common plan or draft drawn up

before the first blow was struck.” Lincoln says this house called the United

States, with all its different pieces made by different people, adhere to a

preordained order. In this case, Lincoln refers to the divine destiny as

accorded by Providence. In one short speech he hits upon all the tenets of

Manifest Destiny.

Lincoln’s next speech, the short but

poignant Gettysburg Address, contains perhaps the most overt Manifest

Destiny imagery that we read in class. To describe a nation as “brought forth on

this continent, ... conceived in Liberty” is to directly tie its descent from

the divine. Liberty, being a common personification of freedom during the time,

provides a link between human endeavors and God himself, making Americans quite

literally, sons of God. As sons of God, they are “to be dedicated here to the

unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced,” and

carry on the mission to preserve and enhance the Union. Lincoln is playing up

the idea of a nation that carries a glorious burden upon its shoulders, and that

it is in “a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so

conceived and so dedicated, can long endure” its burden. The mission of the

United States is clear to Lincoln in this speech; the question is merely can the

nation partake that mission effectively?

Lincoln’s final speech for our class, The Second Inaugural

Address, sees Lincoln focus more on the virtue of the American people he is

now attempting to reunite. His final words in the speech seek to play upon that

supposed virtue:

“With

malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God

gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to

bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and

for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and

lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations”

This passage is meant to appeal to the virtue, one of the

tenets of Manifest Destiny, of the American people. Their common decency towards

each other, a desire to fix the rending of the nation that had just befallen,

and a call to the work yet to be done are meant to play up the idealized notions

of what it means to be an American. Lincoln, in these Romantic words, espouses

the ideas of the Manifest Destiny as ideas of what it means to be American.

Literature of Manifest Destiny: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s lecture The Young

American gives Emerson’s views on the emerging American sense of self. That

he sees America “beginning to assert itself to the senses and to the imagination

of her children, and Europe is receding in the same degree” implies an inherent

superiority to the peoples of Europe. Here, the appeal to America’s inherent

virtue, and that of its children, is being used to spur education so that

America can accomplish its mission of “the task of surveying, planting, and

building upon this immense tract” of land. Already, virtue and mission are being

mentioned, and both in context of the American People. Emerson here seeks to

instruct the young American in what he is to do with this astounding tract of

land, to allow “Destiny, sublime and friendly” to guide them to the goals it has

set before them. Emerson, in saying that a Divine presence was guiding America

toward a noble future, reflects the idea of Manifest Destiny; of stretching out

over the land westward, and inhabiting it as God saw fit.

Emerson again reiterates the ideas of

Manifest Destiny in his essay Nature. To the American he espouses “know

then, that the world is made for you...All that Adam had, all that Ceasar

could,” and to “build, therefore, your own world.” America can be said here, to

be the heir of Adam’s promise, dominion over the world. America is also the heir

to Rome’s promise, of ruling the whole of the Earth and of all peoples being

Roman. The mission has been passed down through Rome, the center of

Christianity, through Adam, who comes direct from God. The mission is to

multiply and expand unto the ends of the Earth. It is the divine destiny, as

descendents of Adam and Ceasar, to rule over the lands. By the virtue of those

men, so do too do the American people have virtue. The American people, with

“beautiful faces, warm hearts, wise discourse, and heroic acts” are the heirs of

the earth (Emerson).All of these words simply reiterate the same message;

America is bound to bring the world into civility, by the nature of their

mission, as ordained by God himself.

Literature of Manifest Destiny: Henry David Thoreau

While no fan of the American government’s

machinations of expansion, Thoreau nonetheless advocates the inherent virtues of

his own American people, and of the American continent. In his essay Walking,

Thoreau sees “the heavens of America appear infinitely higher, the stars

brighter, I trust that these facts are symbolical of the height to which the

philosophy and poetry and religion of her inhabitants may one day soar.” Thoreau

paints America’s destiny as being one of much greater potential than her Old

World ancestors, and that the peoples may raise above. In a Transcendental

sense, America is the very embodiment of the desire to strive for a higher form

of law, thought, and custom. Thoreau goes on to state :

“I trust that we shall be more imaginative; that our thoughts

will be clearer, fresher and more

ethereal, as our sky — our

understanding more comprehensive and broader, like our plains—our intellect

generally on a grander scale, like our thunder and lightning, our rivers and

mountains and forests, — and our hearts shall even correspond in breadth and

depth and grandeur to our inland seas”

-Walking

Here, the Manifest Destiny of the United States is shown as

reflective. The very physical shape of the continent, the way it rises higher

than any other, corresponds with the higher virtues and destiny of the American

people. Thoreau sees America as specially made for Americans, and their unique

place in the world, and marvels at it. What a thought, that a land would bend to

the shape of its people, instead of vice versa. How wonderfully Romantic a

sense, to have a place set out, made just for one’s self, reflecting the higher

thoughts inherent in the self. Thoreau understood and saw through the eyes of

Manifest Destiny, in that he marvelled at the landscape bequeathed to his

people.

Websites

When researching Manifest Destiny, I was hoping to find a

catalogue of all the variations of ideas that lead to the final phenomenon we

know of today. What I found was an entire website dedicated to an extensive

essay done by Micheal T. Lubragge, of the University of Groningen. Groningen is

located in the Netherlands, and as such, this website provided an outsider’s

view of Manifest Destiny. I have to admit I spend a number of hours just reading

the background of the movement, from its beginnings in the “City Upon A Hill”

speech in Puritan New England, to the rousing expansionism of James K. Polk.

What the website uncovered for me, was an understanding that Manifest Destiny,

while coming to a head during the American Renaissance, was an idea as old as

America itself. We have always considered ourselves as set apart from the world,

and it should come as no surprise that we continue this belief. The outsider

view was also quick to remind us of Manifest Destiny’s darker sides, in the

removal of Indians onto Reservations, aggressive actions towards nations such as

Spain, Britain, and even Mexico, another colony turned republic. You would think

being birthed out of the same circumstances would lend us some sympathies with

that sister nation of ours, but the tightly held xenophobic rationales of

Manifest Destiny demanded that it be Anglo Americans that colonized, not those

of mixed Indian descent. It also served as a reminder that a large portion of

the United States did not share the view of Manifest Destiny, and that there

were many detractors to expansionism, namely the Whig party. Reminding us of our

own history, without nationalist bias towards our own personal mythos is an

important function of this site.

This outside perspective is necessary to paint a whole picture of the movement

as it happened, as history does not just occur in a vacuum, but interacts with

the whole world.

Also reviewed was another site, The PBS

overview of the Mexican American War, which includes an entire section on

Manifest Destiny. This is the Manifest Destiny you learned about in school,

given from, while a historical viewpoint, is still in favor of US interests. As

such, the darker aspects of Manifest Destiny are played down, while the

realities of clashes with Mexico are brought up in far more detail than the

Groningen website. It is also a simpler read, and is made up of many more

contributors. It represents more of an amalgamation of American historian

viewpoints, compared to the single essay by an outsider. It also gave more links

to future American Imperialism ideas, and more clearly outlined how they

extended from Manifest Destiny.

Conclusion and What I Learned

What I came to realize from this assignment, with all of its

reading, and analyzing and re-reading, was a new view on the American

self-image. I had always thought that America, and Americans, were simply a

little full of themselves. After all, we are the land of plenty, with vast

tracts of land and natural resources, a powerful economy and military, and major

influence worldwide. I merely thought that America attitude was an extension of

these things. But through reading, I see that it was far older, and more deeply

rooted than simply pride. The idea of American exceptionalism, of being set

apart as better, is as fundamental to the idea of America as is the concept of

freedom. The two are directly linked. That idea of being exceptional was seen as

represented by the vast continent we found ourselves on. It is a necessary

component to travel far distances, over distant plains, harsh mountains, and to

faraway forests, just for the chance at freedom. America, and her sense of

Manifest Destiny, grew not just out of a desire to expand, but a desire to rise

higher than any nation that ever way. Swept up in the boundless potential, is it

any wonder the nation, weary of war, would Romanticize its very existence, and

its land? We wanted a chance to try our experiment at democracy, and to believe

ourselves worthy of its rewards, and strong enough to carry its burdens. I know

now why we study the American Renaissance era; because we as Americans, base our

entire culture on that Romantic notion of being on a mission. Americans are here

to share America, that Romantic idea of equality, freedom, and happiness.

Works Cited

http://www.pbs.org/kera/usmexicanwar/prelude/manifest_destiny_overview.html

Thoreau, Henry Davidhttp://thoreau.eserver.org/walking2.html

Emerson, Ralph Waldo

http://www.emersoncentral.com/youngam.htm

O’Sullivan, John L

.http://web.grinnell.edu/courses/HIS/f01/HIS202-01/Documents/OSullivan.html

White, Craig

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/xhist/MexAmWar.htm

Lubragge, Michael T.

http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/essays/1801-1900/manifest-destiny/

Merk Frederick. Manifest Destiny and Mission in American

History: A Reinterpretation

First Harvard University Press. Print 1995

Bates, Katherine Lee. “America The

Beautiful”

http://kids.niehs.nih.gov/games/songs/patriotic/americamid.htm

"Great Star" flag of pre-Civil War USA