|

|

LITR 4231

Early American Literature 2010 research post 2 |

|

Sarah Wimberley

Education for Early American Women

In Early American Literature we have had the opportunity to gain the perspective of many different authors throughout American history. We have been able to have a glimpse into the lives of American Indians, early settlers, slaves, as well as a look inside the lives of early American women. At the beginning of the semester the question of collective history was proposed. We were asked if we could gain an understanding of a true historical experience without access to all who were involved. The answer to that question is a definitive no. With that in mind, Id like to take a look at a group that is often overlooked; the education of women.

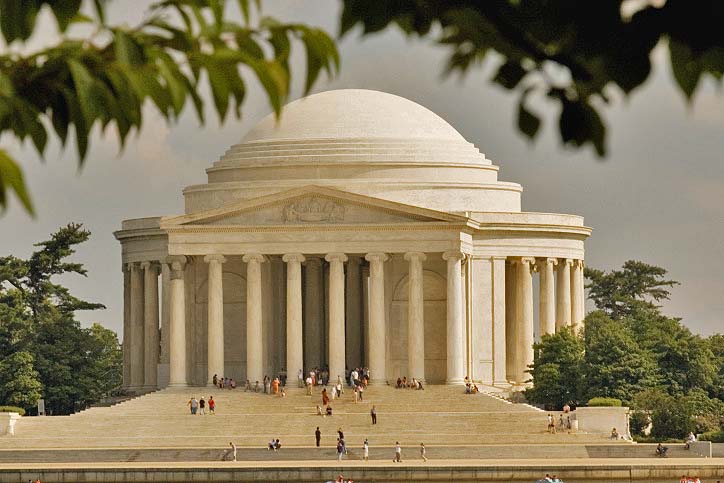

Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to Nathaniel Burwell in 1818 regarding the education of women as he saw it. In this letter he states that he sees that it is important for women to be educated. His attitude toward the education of women was not one that would allow for the development of a career or so that a woman could gain notoriety in government. Rather, he felt that a woman needed an education so that she may share her knowledge with her daughters and play an implemental role in the education of her sons if the father was unable to perform the duty. Jefferson found himself repulsed by most fiction novels and poetry alike. He stated that the reading of such would impede on ones judgment and morality. He listed a short group of books he found appropriate and not offensive to morality. Clearly, his idea of education was very different from that of modern times. Jefferson wanted women to only be exposed to what he saw morally acceptable. This attitude was matched by society in the 1800s as women were forced out of a public education upon the completion of grammar school. Women were thought to be far less intelligent than men, and the powers at be did not see a reason to allow a woman to continue on. She was, however, permitted to be education within her home if her parents were able to provide that. In 1818 a breakthrough was made when Jefferson offered his public support to a woman named Emma Willard. Willard protested the unfairness of the situation and was given a $4,000 grant to open a seminary for women in New York. Her pioneering efforts began the long process of equal rights to education for women. A few years later, Oberlin College in Ohio allowed men, women, and people of color admittance. However, women were only allowed to take the classes that prepared them for motherhood. In 1837 the first true breakthrough for the education of women was established within the Seven Sisters. These Seven Sisters were seven colleges thought to be the equivalent to the Ivy League schools attended by men. In the 1800s strides were being made toward equality in education for both men and women, however, womens education was highly restricted and not yet accessible to all.

Another element of education mentioned in Jeffersons letter was what he referred to as ornaments. Ornaments were dancing, drawing, and music. The tone in Jeffersons letter leads one to believe that he thought the arts were important, but only for the young and rather for the amusement of the young and their parents. Jefferson stated that dancing was a good form of exercise, and that any loving parent would be proud to see their daughter dancing elegantly. He, however, thought that a woman should not be permitted to continue dancing after marriage as that would be inappropriate and take time away from her duties as a mother and a wife. Clearly, the attitude at the time was that a womens full purpose in life was to find a husband and rear children. As far as drawing was concerned, Jefferson found it to be of little use. He felt that drawing was good for nothing more than amusement, but that it could possibly be of use when educating the children in the home. He definitely felt that drawing was of the least value in terms of the usefulness of the arts. Not surprisingly, Jefferson felt that music was of the greatest value in respect to the three ornaments he laid out in his letter. He stated that only those who are musically inclined should participate, but that music got the early Americans through life. It helped them relax and took their mind off the stresses of life. Jefferson felt that music is the only art of sustaining value that a women should participate in long term, but only if she was good at it. Most women were above and beyond anything else in their lives expected to be a housewife devoted to her husband and children without any goals outside the home. As we have seen throughout the semester some women fared better in the arts than did others. There were a few exceptions to the rule, and some women were successful in publishing their novels and memoirs. Although, the majority of women were less privileged in the arts and continued their lives within their respective homes.

Women and education were a touchy subjects among American men in the 1800s. Women had to fight for their rights to education and every other privilege that men were privy to in early American society. Some women were able to gain an education and even to become published authors, poets, and artists. Most, however, were devoted housewives making sure the running of their household was smooth operation and that their husbands and children were attended to properly. The education of women in the early 1800s was a question of morality among the powerful men in that they felt women were meant to be nothing more than homemakers as they were less intelligent in useful than men outside of the home. Thanks to the pioneering efforts of a handful of tireless women the doors to education were slowly opened and women eventually became eligible for such privileges.

Works Cited

Sheffield, Wessley. "Westward Expansion." The Idea of Women's Equality and it's Migration Throughout American History. Sonora Elementary School, 1997. Web. 26 Apr 2010. <http://www.angelfire.com/ca/HistoryGals/Index.com>

Jefferson, Thomas. "Letter to Nathaniel Burwell on Women's Education." LITR 4231 Early American Lit. Dr. Craig White, UHCL, 2010. Web. 26 Apr 2010. <http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/LITR/4231/default.htm>.

Sutton, Bettye. "19th Century Cultural History." Kingwood College Library. Kingwood College Library, 6/2008. Web. 26 Apr 2010. <http://kclibrary.lonestar.edu/19thcentury1800.htm>.

NWHM, . "The History of Women in Education." National Women's History Museum. NWHM, 2007. Web. 26 Apr 2010. <http://www.nwhm.org/exhibits/education/1800s_1.htm>.

|

|

|

|