|

|

LITR 4231

Early American Literature 2010 research post 2 |

|

Lori Arnold

April 19, 2010

Women’s Education in Early America

As a home educated student, I have always been particularly fascinated with theories and methods of education. I also find it interesting to look at the education of important historical figures. Education has the power to shape how a person develops and who they become. As we have studied a few important female authors such as Anne Bradstreet, Mary Rowlandson, and Phyllis Wheatley, I have become intrigued by their literacy at a time when few women were literate or well educated. In our class we have also discussed how the Puritans focused on education including education for women. Thus, I would like to consider how women were educated in the early United States by looking at the means of instruction, what subjects they were instructed in, and the purpose for their education.

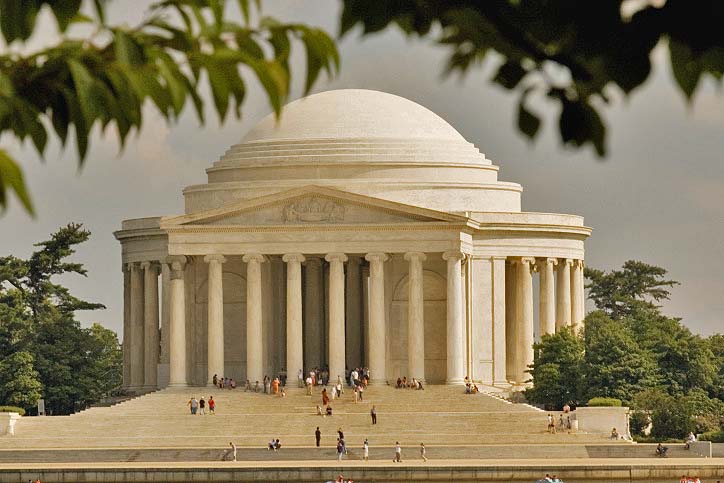

Through the website for Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, I did most of my research about women’s education in the South both just after the Revolution and in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in Virginia has done extensive research about Colonial life in Virginia, which becomes even more important because of the influence Virginians had upon the founding of the United States. Men such as Thomas Jefferson took special care regarding their daughters’ education. “Women and Education in Eighteenth-Century Virginia” by Linda Rowe provided significant information about the type of education gentry planters in Virginia provided for their daughters. Rowe also provided some details regarding the subjects that the girls studied and how extensive their education was. “The Adolescence of Gentry Girls” by Catherine B. Hellier also provided some explanation about the purpose of education in Colonial girls’ lives. This is important because my research revealed that this motivation for women’s education changed between the American Revolution and the Civil War.

My research through JSTOR provided additional information regarding the education of young girls in the South, particularly Virginia. “Equally Their Due: The Education of the Planter Daughter in the Early Republic” by Catherina Clinton in the Journal of the Early Republic gives very interesting information about the growth of women’s academies in the antebellum South. This article explained the importance of British influence on the education of planters’ daughters. Southern Planters in the early United States took cues from British education for women because the planters considered themselves upper class and wanted their daughters to be cultured and well educated. Following the Revolutionary War, planters began to take an active interest in their daughter’s education because they viewed mothers as important influences in the shaping of the new nation. While girls’ education previously focused on primarily homemaking and housekeeping skills, the new focus sought to provide girls with practical literacy skills that they could pass on to their children. Thus, elite ladies’ academies sprang up to provide young girls with a different and more advanced education than they would have previously received at home or with their brothers in early childhood.

Both before and after the Revolutionary War, girls’ education focused on preparing them to be good wives and mothers. Some parents took little interest in the formal education of their daughters and were primarily concerned with training their daughters to run a household by having them help around the house. Less well-to-do families would need the labor that their daughters provided. Other parents, most notably Thomas Jefferson, took great care to educate their daughters in academic subjects.

Prior to the American Revolution, girls often learned how to read and write from their mothers or from a tutor employed to educate their brothers. However, they rarely received formal academic education outside of the home. Rather, they would attend dancing schools or take music lessons in order to become accomplished, marriageable young women. Their education focused on things such as: “cooking, sewing, and household management; reading writing, and perhaps a little arithmetic and French; and a number of other niceties such as polished manners, musical training, dancing, drawing, and fancy needlework” (Rowe 2). These skills were considered very important for girls in order to prepare them to be good wives and mothers. Girls were usually restricted to subjects that were considered necessary to become good wives and mothers. Eliza Custis, the granddaughter of Martha Washington, received an excellent education from a private tutor; however, even she was restricted in the subjects she could study. “When she wanted to learn Greek and Latin, however, neither the tutor nor her stepfather would permit it, explaining that ‘women ought not to know those things’” (Rowe 5). Thus, these girls were obviously restricted in a country that was supposed to provide them with freedom. However, training good wives and mothers helped raise generations that would support the new nation.

There was a strong emphasis in both periods on giving girls the accomplishments that would enable them to be seen as attractive mates and the practical skills to manage a home effectively. After the American Revolution, the method of education changed drastically in the South among gentry planters. “Women wanted to teach their children themselves, but demands of household and plantation management left them little time to spare” which ultimately caused a changed in the way that young girls were educated (Clinton 44). While the South had very few adequate teachers, they were anxious to obtain good education from Northern teachers. This desire to improve their daughters education led many Southern planters to found academies. “Boarding schools were founded to provide suitable facilities, as well as a sophisticated course of instruction” (Clinton 46). Although it was not easy for families to part from their daughters, these boarding schools were supposed to give them a better education than they could receive at home. The curriculum of these academies advertised a broader range of subjects and promised to provide Southern daughters with the necessary skills to catch an eligible gentleman. “An 1826 handbill for the school advertised courses in English, Latin, arithmetic, geography, astronomy, ancient and modern history, natural philosophy and chemistry, moral philosophy, and the standard fare of penmanship, epistolary composition, and Bible study (Clinton 48). This is an impressive list of scholastic subjects, which would provide any girl with a good education. It is also quite obvious that this list differs quite extensively from the standard education for Southern girls pre-American Revolution.

Girls in the South both before and after the American Revolution were expected to become good wives and mothers. Their education was supposed to serve this purpose. However, how parents allowed girls to spend their free time differed according to the type of education they were given. According to Hellier: “In the second half of the eighteenth century, many Virginia gentry parents allowed daughters in their late teens a time of considerable freedom before they assumed the adult responsibilities of marriage” (1). Because their education ended early, girls were allowed a great deal of free time. They often used this free time to enter the courtship circle by meeting young men in the surrounding countryside. However, adolescent girls who attended ladies academies had a more restricted schedule. Most of their time was filled with studying scholarly subjects. While they did have a disciplined schedule in the academy, young girls were still presented to the eligible young men following the completion of their education. Thus, while the method of education for adolescent girls in the South changed following the American Revolution, the ultimate goal to educate future wives and mothers remained the same.

Clinton, Catherine. “Equally Their Due: The Education of the Planter Daughter in the Early Republic.” Journal of the Early Republic. 2.1 (1982): pp. 39-60. Print.

Hellier, Cathleene, B. “The Adolescence of Gentry Girls.” Colonial Williamsburg Research Division Web Site. Web. 5 April 2010.

Rowe, Linda. “Women and Education in Eighteenth-Century Virginia.” Colonial Williamsburg Research Division Web Site. Web. 5 April 2010.

|

|

|

|