|

LITR 4326 Early American Literature Model Assignments |

Final Exam Essays 2017 Sample answers

for

|

|

Tanner House

How Should We be Remembered?

The concept of “Culture Wars” is a uniquely American phenomenon which

likely stems from the hectic and diverse story of American history. American

history is unique in the sense that it seemingly only began about 500 years ago,

when European explores “discovered” the new world, and in the time that has

passed since then it has hurtled forward at an unprecedented rate, often leaving

entire cultures behind. The story of American history is largely incomplete,

since many of the cultures native to the continent kept no records and had no

written language, and this often leads people to disregard certain aspects and

cultures which played a very large role in the “story of us”. These once

abundant cultures are mostly gone now, and many people no longer consider them

relevant or interesting. This is a huge problem, as it leads us to not only

disregard some of the most monumentally important developments in human culture

and history, but also because it causes us to perpetuate and normalize an

objectively incorrect narrative of our history. This idea makes the study of the

true American history all the more important, and all the more interesting.

One of the primary concerns of the western conception of history is the

idea of an origin story, a definitive tale of our roots and where we came from,

and we have plenty of them. Revelation, Prometheus, and even the theory of

evolution are all common and widely known stories and explanations for who we

are and where we came from. These are all also ideas that have a number of

similar overarching themes, likely meaning that there is some idea of conception

or creation that is a human universal. The dominance of the Anglo Saxon culture

in America has resulted in a particularly European flavor which lingers in our

myths and stories, and it is beginning to leave a bad taste in our mouths. Many

of the ideas which get credited to the Anglo Saxon culture clearly did not

originate, or were not original to, said culture. If we take a look at any of

the Native American origin stories which we have studied this semester, the

common themes of creation and purpose found in the European creation myths are

prevalent in the Native American creation myths as well. So why are the European

stories romanticized while the Native American stories are often criticized, or

even outright ostracized? This idea can be explained through further study of

our course material.

John Smith’s “History of Virginia” gives us an early and immediate

example of the idea that the true narrative of American history has been

embellished and corrupted. Many of Smith’s accounts of his encounters with the

Native American people are so outlandish and absurd that they may as well be

fantastical. On a skirmish between his expedition and the native people, the

history claims, “Smith, little dreaming of that accident, being got to the

marshes at the river's head, twenty miles in the desert, had his two men slain,

as is supposed, sleeping by the canoe, whilst himself by fowling sought them

victual: finding he was beset with 200 savages, two of them he slew, still

defending himself with the aid of a savage his guide, whom he bound to his arm

with his garters, and used him as a buckler, yet he was shot in his thigh a

little, and had many arrows that stuck in his clothes; but no great hurt, till

at last they took him prisoner. When this news came to Jamestown, much was their

sorrow for his loss, few expecting what ensued.” John Smith never strapped a man

to his forearm and used him as a shield, and his prowess as a warrior was

nowhere near that of Achilles. He could not single handedly defeat anywhere near

the number of men whom he claimed he had, and he could be killed just as easily

as the countless men who had been killed before him. John Smith’s contributions

to history are not at all unimportant, as he fulfilled a vital role in early

American history as a mediator between the Native Americans and the European

settlers. But the stretch from mediator to godlike, untouchable warrior is

pretty significant, and serves as a prime example of the corruption of the true

narrative of American history.

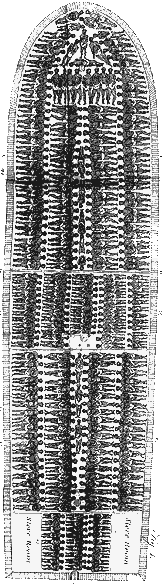

Just as prevalent in American history as embellishment is hypocrisy. If

we hold these truths to be self-evident, and all men are created equal, then why

was it that for a few hundred years only white men were allowed to own property,

or serve in a governmental capacity?

The concepts of liberty and equality were on the forefront on the

foundation of the new world, but only when they applied to the European settlers

who, for all intents and purposes, had invaded the continent. The “Model of

Chrisitan Charity” asserts that “There is likewise a double Law by which we are

regulated in our conversation towards another. In both the former respects, the

Law of Nature and the Law of Grace (that is, the moral law or the law of the

gospel) . . . . By the first of these laws, man as he was enabled so withal is

commanded to love his neighbor as himself. Upon this ground stands all the

precepts of the moral law, which concerns our dealings with men. To apply this

to the works of mercy, this law requires two things. First, that every man

afford his help to another in every want or distress.” As far as moral codes go,

this one does not sound so bad. It seems to lend itself quite well to a peaceful

and cooperative existence, and in many instances this was indeed the case. The

story of the history of early America is not entirely composed of deceit and

bloodshed, and there are many documented cases of productive and peaceful

coexistence between the natives and the invaders. But for every peaceful

exchange there seems to be twice as many violent ones, due largely in part to a

fundamental misunderstanding of humanity. Early America even had the best

intentions, as liberty and peace were the foundation of many of the settlements

of the new world, but hypocrisy and violence still proved too powerful

temptations.

The further the timeline of Early America progresses, the better things

seem to get. The initial upheaval that accompanied the original settlement

starts to die down, and a new way of life begins to take hold. The new American

people move past their conflicts with the natives and set their sights on

seemingly grander issues. And the grander the new issues seem, the less we pay

attention to the old ones. Who has time to talk about the systemic genocide of

an entire hemisphere of people when the heroes of American mythology were

singlehandedly putting an end to generation’s worth of tyranny and oppression?

George Washington comes off in a much better light when we paint him as a

revolutionary hero and the father of the great American democracy, which by all

accounts are both things that he was. “Washington’s wooden teeth” are a very

popular symbol in American mythology, but they also were not real. Washington’s

dentures were made of teeth that he had pulled from the mouths of slaves. Just

as much as we (often rightfully) romanticize so many aspects of our history,

perhaps now we should begin to, if not quite vilify, then at least objectify

them.

In continuing with the courses texts and themes, I have spent a lot of

time reconsidering my earlier stance on “vilifying” the founding fathers of

American history. Their legacy is so complicated that it becomes difficult to

view through an objective lens, but in attempting to do so I have realized that

what these men did, and the circumstances that brought them together, are so

important that they really should not be seen as anything less than heroes.

Never before has such a collection of intelligent and influential men been

assembled, and to assemble in the name of liberty and equality, no matter how

relative the terms might have been at the time, is a remarkable achievement.

When we consider the model for government that the United States constitution

provides us with, it becomes easy to realize just how important of a

contribution these men made to history and humanity. When the constitutional

convention assembled, a collection of the most intelligent and influential men

on the planet began a discourse on how to best ensure the possible existence of

an entirely free and independent state. It was about so much more than any one

man, or any one topic. It was the beginning of what we now know and love to be

Western civilization, and it would have been entirely impossible without

happening exactly the way that it did. It was proof that there was a place in

modern politics for liberty, and for equality, and for something as close to

justice as men could ever come. In seeking to objectify this I fear I may have

attempted to spoil one of the most important and monumental achievements in

human history. Yes, much of Early American literature seems to embellish and

romanticize the truth of what happened, but Early American literature seeks to

explore and redefine what humanity is capable of. For the first time in history,

we have clear evidence that the human will cannot be triumphed. Through nothing

but desire and a sense of morality, a new state was created on the foundation of

ideas that were once only considered to be dreams.

This is all reflected through the exploratory nature of Early American

literature. The revolutionary spirit found its way into the cultural zeitgeist,

and I am not entirely sure that it ever went away. In studying Early American

literature, we see the profound realization that through literature we can

achieve social and political revolution on a global scale, and that the topics

explored by literature are so important, and so necessary to the survival and

advancement of the human race that understanding how we understood them in the

moments when they were produced is absolutely necessary in continuing to create

works which do the same thing. Early American literature is the blueprint for

the spirit of Western Civilization that still drives our curiosity. Without it

we cannot understand ourselves, or the freedom which we are allowed to practice

to formulate that understanding.

|

|

|

|