|

LITR 4231 Early American Literature |

Final Exam Essays 2014 Sample answers

for |

|

Jonathon Anderson

“The bud disappears when the blossom

breaks through”

It seems that most courses tend to

focus on one topic or point in time. So far at UHCL I’ve taken Literary Genres

and Perspectives (which focused on the elements of literary criticism),

Victorian Literature, and American Realism. At first glance, Early American

Literature seems like a similar undertaking, and considering the commentary

offered by some previous students on other approaches to “Early American” texts,

it may be similar for many professors (Rochelle Latouche’s

Evolution of American Literature,

Native Misconceptions,

Jillian Norris’s

Exploring the Unknown in American Literature).

Compared to a roster of readings that may span fifty or sixty years, the

audacity of proposing to start with a text written in 1492 at the exact moment

of the creation of an American literature (if we define American literature as

the intellectual meeting point between European culture and the preexisting

culture of the Americas) and then traverse roughly 300 years of social and

intellectual development is mindboggling even if we confine ourselves to a

limited geographical area.

The only other courses I’ve ever

encountered with as large a chronological scope are Music History I and II

(ancient Greece to the Middle Ages and then the Renaissance to the Modern era)

and a Western World Literature course that started with Gilgamesh and ended with

the Renaissance. In both of these instances, the concept of the historical

period is used to organize the work of the hundreds (or even thousands) of

individual artists into more manageable groupings. As the “Periods”

webpage explains, by understanding the basic trends in aesthetic taste, the

patterns of intellectual thought, and cultural values at certain points in time,

we can more easily talk to each other about the idiosyncrasies of individual

artists as well as the sometimes elusive steps in the evolution of the arts and

culture up to and including the present day.

However, this can threaten to be

counterproductive to efforts to see continuity in history. Once we learn the

“rules” for a period, we can make the mistake of only evaluating works by our

preconceived notion of what they should

be instead of using those “rules” as one among many tools that are helpful in

decoding the unique intellectual singularity that each artist represents. The

idea of periods of time during which only one script is possible can even make

historical development seem like a series of revolutions and counterrevolutions

as representatives of the Renaissance overthrow the Middle Ages or the Romantics

discard the Enlightenment. Upon closer investigation, though, historical

development reveals itself as less a cycle of upheaval and rejection and more an

evolution in which new ideas are transformations of previous ideas and new

translucent layers of meaning are applied like a fresh varnish. For the early 19th

century German thinker Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, reality is a continual

becoming or evolution.

"The bud disappears when the blossom breaks through,” says Hegel, “and we might

say that the former is refuted by the latter; in the same way when the fruit

comes, the blossom may be explained to be a false form of the plant's existence,

for the fruit appears as its true nature in place of the blossom” (7). Although

we might not accept completely the comparison (as I don’t), since we don’t tend

to think of each successive historical period as an improvement over the last,

it does clear the way for the useful concept of the bud, blossom, and fruit as

“moments of an organic unity, where they not merely do not contradict one

another, but where one is as necessary as the other; and this equal necessity of

all moments constitutes alone and thereby the life of the whole.”[1]

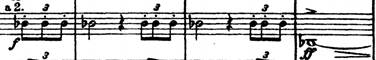

A very cool idea Dr. White uses to aid us in building our thumbnail-sketch

understanding of historical periods and how they overlap each other is the

inclusion of representative music, art, and architecture. A brief look at

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony will show both how this can accelerate the learning

process and how ideas are adapted and transformed through time in Hegel’s

process of continual becoming. One of the most easily recognizable features of

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is the

opening:

![{\clef treble \key c \minor \time 2/4 {r8 g'8[ g'8 g'8] | ees'2\fermata | r8 f'8[ f'8 f'8] | d'2~ | d'2\fermata | } }](clip_image001.png)

Playing just the rhythm of the opening measures, many people will identify it as

Beethoven’s Symphony, but this musical gesture was also present in the work of

Beethoven’s precursors of the preceding Classical period,

Haydn

(Beethoven’s one-time mentor) and

Mozart

(Beethoven’s piano idol and popular inspiration) (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._5_(Beethoven)).

Beethoven adapted and transformed the music he grew up with, utilizing the

musical material in a way that layered a sense of Romantic intensity and drama

over his source material. Nearly one hundred years later, late Romantic composer

Gustav Mahler confronted the problem of the reputation of Beethoven’s Fifth

Symphony head-on in his Fifth Symphony, which reimagines Beethoven’s beginning

as a

Funeral March:

The first few measures of Mahler’s 5th Symphony, featuring solo trumpet. (Score

source: International Music Score Library Project)

The end of the introduction to the first movement.

Although the overall effect is broadly similar in all four cases, each composer

is simultaneously drawing on a continuous historical tradition and transforming

that tradition according to his aesthetic taste,

patterns of intellectual thought, and cultural values.

Similarly, we can see a nexus of traditions in Sor Juana’s “You Men.” The

earmarks of Renaissance style (especially Classical references) commingle with

an appeal to logic and reasoning that will become characteristic of the

Enlightenment in these stanzas:

Presumptuous beyond belief,

you'd have the woman you pursue

be Thais when you're courting her, [courtesan

of Alexander the Great]

Lucretia once she falls

to you. [Roman

victim of rape & suicide] 20

For plain default of common sense,

could any action be so queer

as oneself to cloud the mirror,

then complain that it's not clear? 24

We would not be out of line also to

see a continuation of Christian medievalism (although again transformed) in the

overall moral conviction of her theme. Anne Bradstreet complicates conventional

domestic themes with evidence of Classical learning and a humanist perspective.

Although Jonathan Edwards’s famous

Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God

seems a complete break with any sense of Renaissance culture (except perhaps in

the demonstration and documentation of thorough knowledge of Scripture) and

looks forward to the Gothic atmosphere of Charles Brockden Brown’s

Edgar Huntly, Edwards’s

Note on Sarah Pierpont could easily

be interpreted as a link between an endearingly domestic poem like Bradstreet’s

“To my Dear and Loving Husband” and the early professions of love between

Charlotte and Montraville in Susanna Rowson’s

Charlotte Temple. We can even connect

Edwards to the Enlightenment through his

Personal Narrative, “Of the Rainbow,” and “Of Insects.” While the style of

the Personal Narrative seems a

wonderful anticipation of Romantic intimacy with nature and the self, the

interest in the carefully observed documentation of intellectual and social

development seems of a piece with Franklin’s sometimes funny and often ironic

Autobiography.

A look at the transition or

intermingling of Enlightenment and Romantic culture would be severely lacking if

we did not account for Thomas Paine, whose works are essentially a synthesis of

Enlightenment reasoning and Romantic individuality. In

Common Sense and

The Crisis, he builds arguments

logically that are calculated to appeal to the emotions, and he proclaims the

tenets of Deism in The Age of Reason

without concern for anyone else’s refutation or dissent.

It’s interesting to note that Anne Bradstreet had already arrived at one

of the most characteristic designations of the Deists for God around a hundred

years earlier in her “Verses upon the Burning of Our House,” writing “Thou

hast a house on high erect /

Fram'd by that mighty

Architect.”

The culmination of our semester was a pair of contrasting novels that exemplify

transitional traits. Both feature details that are familiar in the Gothic

tradition, which can be understood as the reciprocal or photographic negative to

the Enlightenment world of reason and order. In Rowson’s

Charlotte Temple, as Lauren Weatherly explains in “A Gothic America: the

Early Years,” the author’s project is to “‘scare’ young girls.” The story

documents our heroine’s journey further and further from the Enlightenment world

of safety, structure, and predictability to an inverted Gothic world of

suffering and chaos. I liked what Veronica Ramirez said about

Edgar Huntly being the “gateway”

between the Enlightenment and the Romantic eras (“Edgar Huntly: The

All-Encompassing Early American Novel”). Charles Brockden Brown, himself a

product of Enlightenment society, systematically robs his title character of all

the accoutrements of Enlightenment society as he subjects him to many of the

same horrors and uncertainties that we saw in Mary Rowlandson’s and Mary

Jemison’s captivity narratives.

By the end of the semester, we have traveled approximately 300 years through the

American wilderness. We’ve seen it transformed into the frontier, into

superstitious villages, into havens of intellectual hope, and again into the

wilderness of early modernity. We’ve seen new layers of meaning settle down on

top of the original struggles of the early settlers, as the experiences of each

succeeding generation enrich and redefine the culture where “one is as necessary

as the other; and this equal necessity of all [cultural] moments constitutes

alone and thereby the life of the whole.”

Works Cited

Weiss, Frederick. “Introduction: The Philosophy of Hegel.” Hegel: The Essential Writings. Ed. J.N. Findlay. New York: Harper & Row, 1974. 1 – 18. Print.

[1]

Hegel’s argument here is a clear illustration of the thread of Romantic

optimism that believes the goal of historical evolution will necessarily

lead to superior artistic and social forms.

|

|

|

|