Instructional Materials for

Craig White's Literature Courses

|

Natural

or story-telling & Essay organization |

|

This page has been translated into the Estonian language by Karolin Lohmus at

Compared to other sentient life forms, humanity's most distinguishing quality is language, especially at a highly developed or complex level (though prehensile hands and social organization are right up there too).

People have been speaking language to each other more more than 100,000 years, and language seems as natural a phenomenon for us as families, teeth, and wonder about what everything means.

But like everything in nature, language evolves toward more complex and ambitious versions of what came before. As an artificial analogy, compare past and present computer languages (or hardware), where each generation is faster and can handle more data than the previous generation.

Since early in human history, people have often used language to tell stories, to the extent that narrative or story-telling is another of humanity's identifying characteristics--comparable only to bees dancing in such a way as to indicate where fellow-bees can find pollen, or perhaps in not-yet-known ways by water mammals like dolphins or whales.

For an up-close example of this human inclination to tell stories, think about your day so far. If you met a friend on the way in this morning, you might have shared stories about last night or what happened since you saw each other last. When our meeting is over, your parents or friends may ask you what this event was all about, and you'll probably come up with a little story that will give your listener some information and some pleasure--you might describe how you saw somebody

Academic

or political writing requires learning skills that may cut against the grain of

natural styles.

Two major transformations must be

learned, though neither is absolute:

· Personal or local content and style > impersonal content or objectivity

·

Narrative or time-sequence (telling a story) > alternative

critical organizations (logic, cause-effect, analysis, critical thinking,

compare-contrast, problem-solution)

1.

Transform or adapt

your natural, personal style to a more impersonal style.

Your personal style can still enliven and diversify the academic or political

style, but the

impersonal style has several advantages:

· Impersonality is more universal. (What is personal may be restricted to the person writing it.)

·

Impersonality permits focus

on a subject that is shared (or might be shared) by a society or group or

audience. Therefore, instead of writing about yourself, you’re writing about a

subject.

These trends

explain why

many writing teachers forbid the use of “I.”

In any case,

use “I” only when

necessary or helpful. For one reason, self-reference is so

powerful that the more you do it, the more the power dissipates, so a general

guideline is to

use “I” freely when drafting, but in revision, use “I” only

when you’re sure it helps. Similarly, avoid “in

my opinion”; instead, just state your opinion in straightforward, third-person

terms.

The writer’s self or identity never goes away completely, and

you don’t want it to. However, the writer’s self or identity works subtly—in

word-choice, in speech-rhythms, in idioms, and in the prioritization of some

opinions, facts, or values over others.

Making your content impersonal (and thus more universal,

objective, and empirical) will be less of a problem in courses like

Psychology, History, or Literature, where you will write not about yourself but

about studies, cases, events, movements, texts, etc. For at least two essays for

our course, you will be writing about what you’ve learned about writing and

related issues, so you must consult your own experiences, but such descriptions

can transform from personal subjectivity to impersonal objectivity:

·

Write about your own

experiences witnessing or thinking through something.

·

Refer to yourself as a

representative of some group, community, or common identity.

Overall, impersonality or objectivity in content means you

shift the focus to knowledge or opinions that everyone has access to, more or

less. That’s why academic writing insists on references and documentation, which

account for how you know what you know and enables your reader to find the same

information as needed.

![]()

Transform your natural inclinations to deliver information through narrative or time-sequence (telling a story)

> alternative critical organizations (logic, cause-effect,

analysis, critical thinking, compare-contrast, problem-solution)

Academic writing requires students to adapt and change some

natural writing and speaking habits. One of humanity’s most strongly engrained

verbal patterns is

personal narrative

with observations (the kind of story people

naturally tell about themselves, acquaintances, or celebrities > lessons or

judgments)

For the most part, academic writing could care less about who

you are, who you know, or a given moment’s celebrities. In fact,

thematic

developments of shared subjects organized by logic or comparable critical

thinking processes. (analyses of topics that

have something to do with all of us, and with the author and his personal world

mostly in the background)

Natural pattern:

1.

Description, facts, story,

events, statistics. ("Did you hear that only half of Americans . . . . That

just shows . . . ."

2.

Outcomes, judgments, lessons

learned, conclusions.

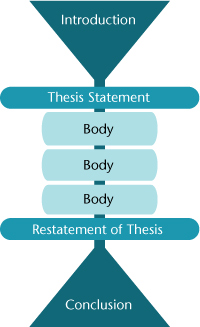

Academic pattern:

1.

Thesis, idea, proposal,

hypothesis, point or sub-point

2.

Supporting facts, logic,

analysis, data, testimony.

In the natural pattern, conclusions or outcomes appear at the end. In the

academic essay pattern, you start with conclusions or hypotheses, then support

or explore them.

Analogy: A lawyer making a case to a jury doesn’t present all

the evidence before saying, “My client is not guilty.” He begins by saying that

all the evidence will prove “my client is not guilty” and then lays out the

evidence. His conclusion, like an academic essay’s, will summarize and

re-emphasize and indicate what should come next.